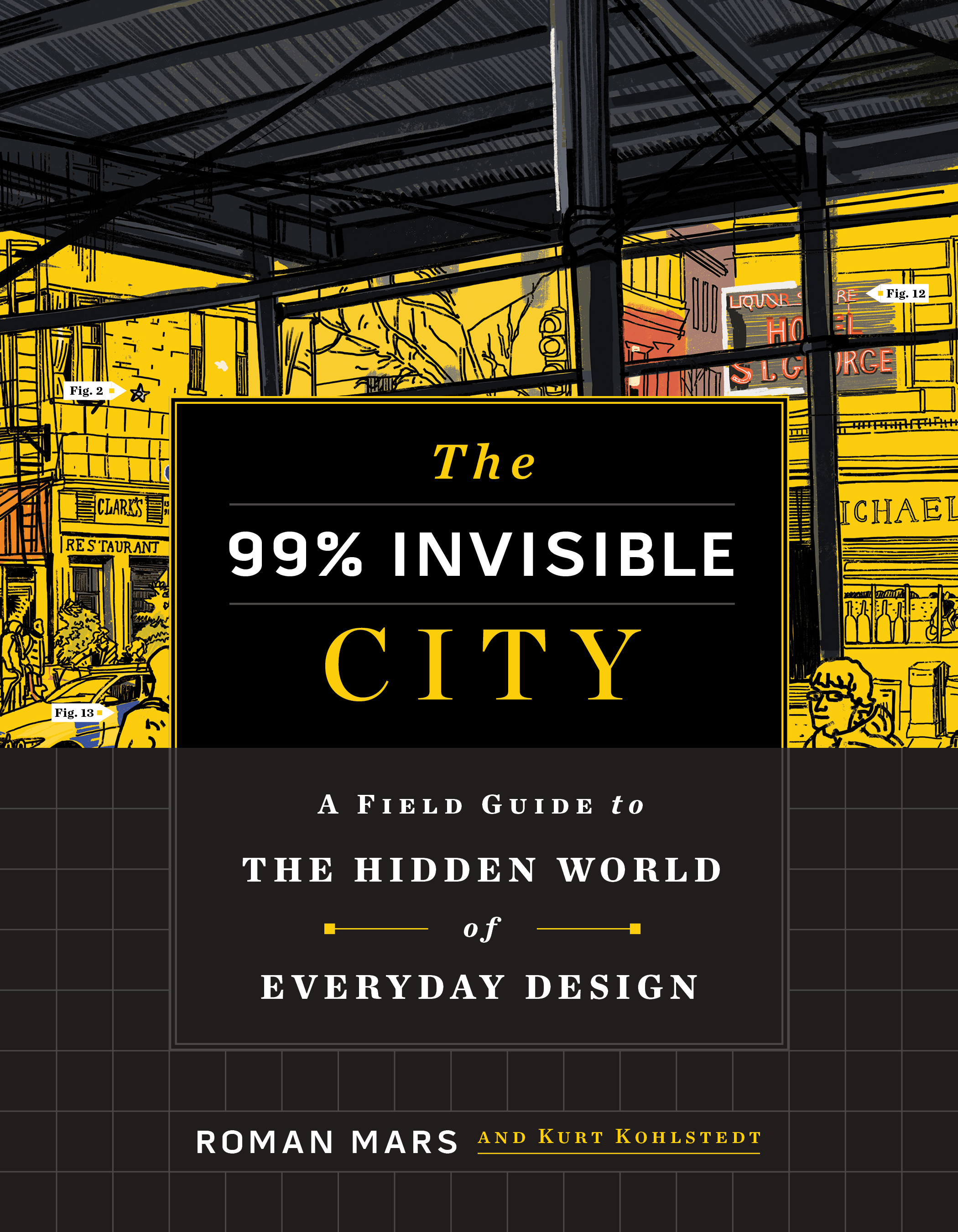

After ten years and 400+ episodes, podcast 99% Invisible has taught everyone from architects to design aficionados how to thoughtfully engage with the world around them, and to think about the ‘how’s and ‘why’s cities work the way we do. When the show first started in 2010, host and founder Roman Mars, like many podcasters, was recording and producing it in his bedroom; now he’s released The 99% Invisible City: A Field Guide to the Hidden World of Everyday Design.

AN interviewed Mars on the evolution of the podcast, what got him interested in architecture, and how The 99% Invisible City (which debuted on October 6 and quickly became a bestseller) diverges from, complements, and even expands the show it’s based on.

The following interview has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

AN: What first piqued your interest in design, and why did you choose a podcast to explore some of the stories behind everyday designs?

I have a natural inclination towards explanatory journalism of everyday things. For a long time, it was more science- or nature-oriented stories rather than design. One of the fundamental things that really changed how I viewed the world was the Chicago Architecture Foundation’s architecture boat tour. Have you done that one before?

I am a huge fan of architecture boat tours; I’ve been on four or five of the New York AIA ones.

The docents were so good at telling stories—it was nice that you could see the buildings from the vantage point of the river, but that wasn’t really required, even. The stories were just good. At the time I was at WBEZ in Chicago, and the boat tour unlocked something for me to make me think I could actually do this on the radio. Maybe there was an advantage to radio, because so much of architecture and design journalism is about the aesthetics of design. Honestly, I don’t have a very refined palate, and I don’t have a strong opinion about the way things look, mostly. I really care about the story and the problem-solving associated with design.

Later, when I was at KALW in San Francisco, the AIA wanted to do an “architecture minute” series on local buildings to run during Morning Edition.

What was the first building you covered?

The first was the Transamerica Pyramid. It was voted the worst building in the city. And later it was voted the best building in the city. I was interested in the story behind that change. From the very beginning, I knew I didn’t want to do a show about just buildings. That’s why the show is called 99% Invisible. I wanted to do a show about decoding the invisible world.

In a 2015 Reddit AMA (Ask Me Anything, a Q&A on the platform where experts field questions from users), a user asked when you were going to do a book. You responded: “There is probably room for another good general-interest design book out there, but the hard part is finding the time to do it while making a new show each week, and the latter is my first joy.” Why did you decide to do the book now?

That’s pretty much the right answer. It’s really hard to do the show and the book at the same time. Kurt [Kohlstedt], my co-author, said “it’s time.” He was ready to push it forward, and I couldn’t do it on my own.

We didn’t want to do a deprecated translation of the show. The field guide breaks open information within 400 episodes of a linear audio format and makes it an easily searchable, scannable, perusable desire path–oriented way through the information.

Does the material mostly come from 99% Invisible episodes?

About 50 percent has some precedent from the show, but it might not be the thing we focused on in the show. It might have been a side [story] in one of the episodes, and then 50 percent is completely new. I made every single one of these episodes, I don’t remember tons of it. It was like—we researched it again for the first time, almost. it was like everything was re-recorded. It has some precedent, but it’s more of an exploration of the worldview we’ve built over 10 years of doing the show.

Could you explain what that worldview entails?

When you pay attention to the information layer that’s encoded into the built world, a) it’s delightful, and b) it makes you optimistic, because you see all these things that people are designing on your behalf, things you may not notice most of the time, because you tend to notice the bad things that don’t work, and you don’t notice the good things. So, the worldview trains you to notice the good things.

One idea that evolved to become the thesis of the book, which is not always the thesis of the show, is that the city is this constantly evolving conversation between top-down designers and bottom-up interventionists, which is the thing we’ve always talked about, but never as explicitly as we do in the book.

The book is a guide to understanding your city in that context. So you start with the invisible things, then the highly visible things, and then the big things and it gets bigger, bigger, bigger— buildings and the geography and then it’s larger and larger in scope, until you get to this final chapter, where some of it is planned, and some of it is ossified ad hoc solutions. Some of it is interventions that are there to correct something, some of them are interventions meant to improve something and to be playful. All of that is the city, and that conversation is what’s fun. The book isn’t a traditional guidebook in the sense that it’s examining something frozen in time or a specimen. It’s a guide to a way of thinking rather than a guide to the sidewalk stamp.

That [worldview] came out through this construction of the book. It was always there in the show. We always had a sense of what design meant, we always liked playful intervention. We‘re basically a history show, not a new design disruption or intervention-type show, because the stories we always tell are “here’s a design, and here’s how we reacted to it over the last 40 years.” I mean, we’ve always been about reflection. The book is like that, too. It’s centered around this idea of being aware of what an evolving city means and what it means to share space.

In school, you take English classes to interpret literature, and you study science to explain things that are not observable to the naked eye, and you take art history to understand why a banana pinned to the wall is a work of art. However, even though we live in it, there are hardly any courses in interpreting the built environment outside of architecture and urban planning. Why do you think that that decoding the built environment isn’t something emphasized in formal education?

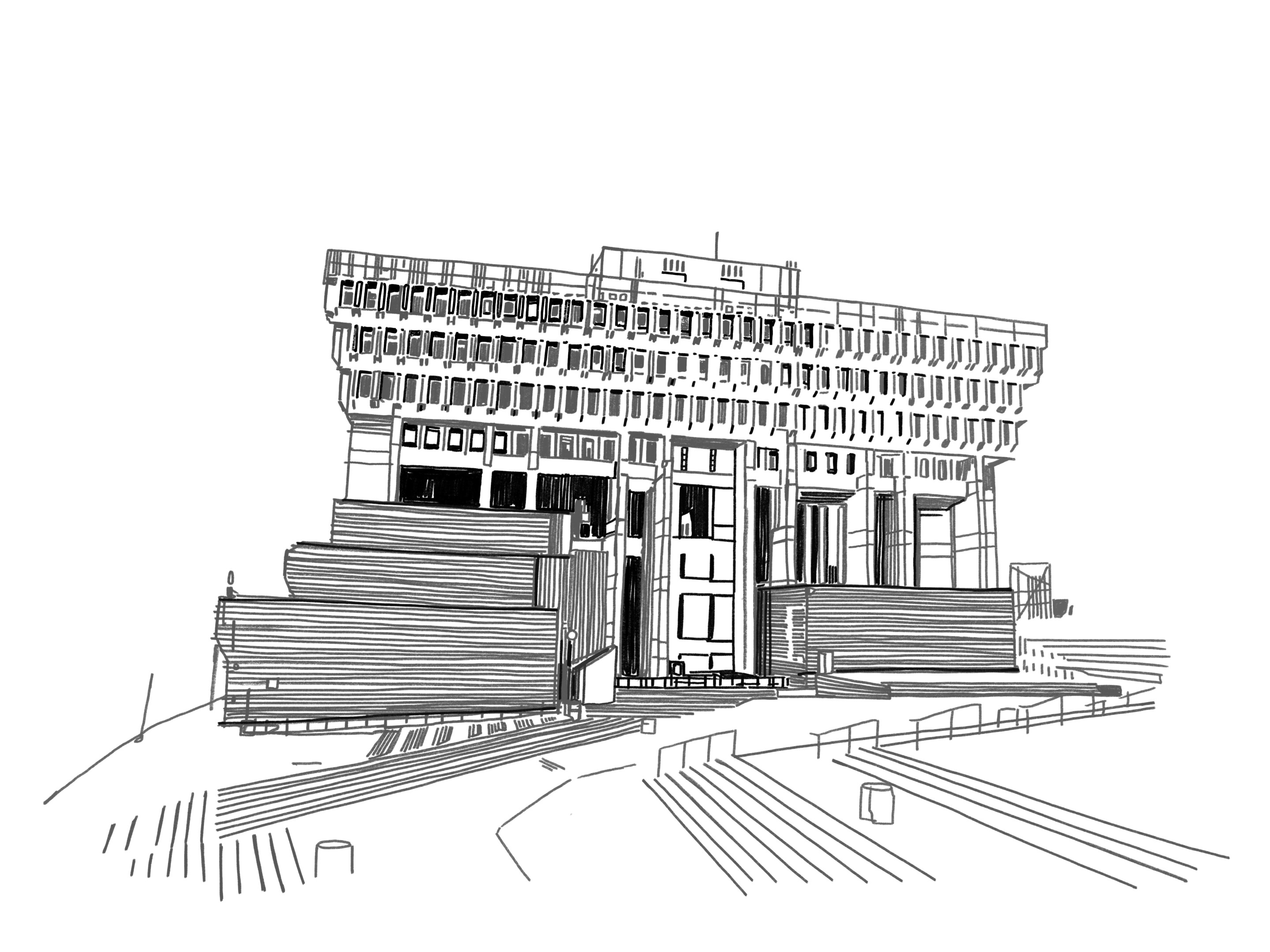

I’m very gratified by the fact that specialists have enjoyed the show, but it’s not meant for specialists. It’s a general interest show for the curious. Architecture education is extremely distancing. There’re lots of “-isms.” There’s a lot of dismissal of people’s gut reaction to the built environment, and architects will go, “Well, you don’t like brutalism because you don’t understand it.”

Guilty.

And it’s true! Getting to know brutalism makes you love it, it’s absolutely true. In telling the story of brutalism you have to at least reference the fact that it makes most people feel awful. Admitting to that, admitting that people have a stake and a say in the art that they live in, and the art that surrounds them, is a good first step to making it more generalizable.

It would be great if there were survey courses for architecture and design in the spirit of “Rocks for Jocks” and “Math for Poets.” We know you’re not going to pursue this topic as a career, but we think that it’s good for your soul to know about igneous rocks. I think it makes a ton of sense because it makes the world more delightful to engage with it.

There are quick and easy rubrics for describing the world without having to know the difference between the International Style and modernism is, which I don’t know if I can articulate that to you myself. It has rigid precepts, and I was a scientist for a long time. A lot of people like to jargon-ize and have high-end conversations to make themselves feel like what they’re doing is important.

I think architecture falls victim to that quite a bit. Within the profession, people are talking about big important things, but 90 percent of the profession is designing bank branches. There’s a heady side to the work, and then there’s the very basic, normal side to the work. What I love is mixing all that up and just finding any little detail, a way for people to get into it, just to go, okay—I know that doing your hundredth Wells Fargo branch design is crushing to your soul. But talking about what a bank branch is versus what a check-cashing store is, and the design choices that are made in terms of who the audience is, that’s interesting. We need to take those mundane concerns and explain them to [non-architects] so they feel like they can figure it out, and they feel invested, and they feel they can be a part of the conversation because they truly can be—we all live in these things.

The text seems to be aimed at adults. Is there anything in here for younger people?

The book’s general spirit is extremely welcoming to kids but not pitched directly to them. But everything except the language is appropriate for kids. I’ve read parts of it to my kids, and they always go “that’s good for a nonfiction story.” They don’t understand why anyone would write anything that doesn’t involve, you know, dragons.

I know kids that use it. One of my favorite pictures we’ve gotten from the book is an eight-year-old with the book open and he’s in the middle of his street looking at the utility codes spray-painted on the pavement.

I grew up before the internet, so I was a kid who just sat in front of the encyclopedias and opened them up and flipped through and found things—those weren’t pitched to me, but I could get what I call it out of them. I hope that the book is intriguing enough to explore. As you get older, you might get more and more of it. If I were to put odds on what the next book was going to be, it would be a kid’s book version of this book.

Were there books that you look to as precedent for The 99% Invisible City? Your approach to analyzing the built environment reminds me of The Image of the City and Outside Lies Magic.

The life-changing book in this canon for me was The Design of Everyday Things, which doesn’t deal with cities, but was a real eye-opener for me in terms of how to think about design as a both as a non-expert and as a logic exercise, rather than a set of formal rules. When I originally thought about our book, I wanted to write it as a new Design of Everyday Things. But it’s unrecognizable as a connection. It’s not a model in any way, it’s just—the delight that that book gave me was what I wanted to replicate.

There’s a little bit of Tim Harford’s Fifty Things That Made The Modern Economy.

I liked the pictures, the drawings, and the abstract sense of something like A Pattern Language. But in a way, I wanted to create [a] book that didn’t exist.

Do you have a favorite entry in this book?

My favorite story in the book, the one that people gravitate to, is the one on Thomassons. They’re vestigial but maintained staircases that go up the sides of buildings, but they lead to a sealed-up door. They go nowhere. Japanese artist Genpei Akasegawa named them after Gary Thomasson, an American baseball player who went on to play for Tokyo’s Yomiuri Giants. They signed Thomasson for a huge amount of money, but he played terribly in Japan: He set an all-time strikeout record in 1981, and warmed the bench for the remainder of his two-year contract. For Akasegawa, Thomasson’s career was a representation of something “useless” but “maintained,” just like those stairs to nowhere. Akasegawa published a book of the vestigial elements he found, as well as examples sent to him by readers from around the world.

Thomassons are one thing that you can go out and try to find in your city that’s a little more obscure. If people like that story, then they’ll like the book.

The 99% Invisible City: A Field Guide to the Hidden World of Everyday Design, by Roman Mars and Kurt Kohlstedt, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, is now available. AN uses affiliate links and may receive a commission for books purchased through those links.