There’s a specter haunting the left critique of architecture: the specter of boredom.

For decades, a cavalcade of scholarly stars—Peggy Deamer, Mike Davis, Fredric Jameson, Manfredo Tafuri, pick your fighter—has turned in thrilling critical performances on Marxist themes, giving us essential and often startling insights into the built environment. But there’s a problem, one particularly evident among a rising generation of architectural thinkers as it grapples valiantly with the world that 21st-century capital hath wrought. It’s a sort of Wittgensteinian dilemma: If capitalism is now “all that is the case,” what particular facts can be deduced about this condition that aren’t merely restatements of the overall premise? That architecture is always and already an instrument of power, economic and otherwise, is a point that certainly bears repeating. Yet just as capital has become increasingly pervasive in shaping buildings and cities, criticism (both academic and, increasingly, journalistic) has resorted more and more to different versions of the same rote response: “It’s the exploitative system of social relations, stupid.”

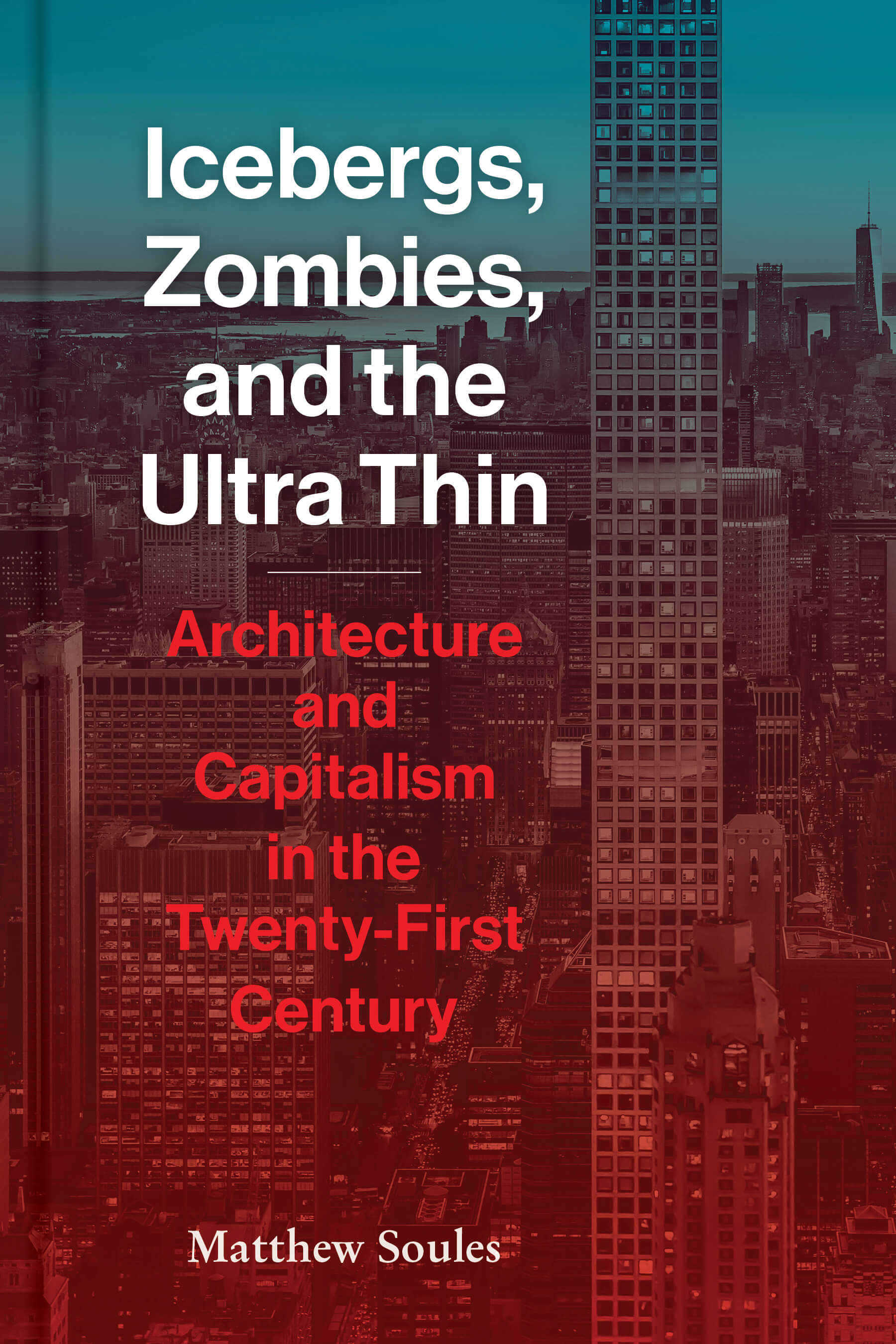

Onto this intellectual merry-go-round comes Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century (Princeton Architectural Press, 2021). The book, by architect and University of British Columbia professor Matthew Soules, is a whirlwind tour of the outrageous physical distortions, urban warp zones, and typological mutants wreaked upon the global landscape by the international finance industry.

We are shown the ghost cities of China, left over from the pre-2008 boom, and the luxury condo compounds of Vancouver, where the wealthy live in splendid isolation atop amenity-packed pedestals. We are informed, and on good evidence, that these and other aberrant products of contemporary architecture are the fruits of a hypertrophied global banking sector that has become the cart pulling the real estate horse. This is to say—notwithstanding Soules’s obvious depth of knowledge and occasional flashes of wit—that for 207 pages, we are mostly shown things we have already seen and told things we already knew. Until suddenly, unaccountably, Soules tells us something else.

While the author is traipsing through familiar terrain, he also brings along some very familiar guides. The above-listed luminaries all put in appearances (alongside Karl himself); this is not always to the book’s benefit, as Soules’s prose does not necessarily shine by comparison. More worrisomely, Icebergs exposes a curious rhetorical catch in the application of some varieties of negative dialectic to architecture. Over and over, Soules regales readers with stories of the investment-mat developments of Spain, “flowing over the Mediterranean landscape like lava,” or of the vacant housing estates of Ireland, where “the carcasses of half-finished shopping malls hulk on the horizon.” Then, inevitably, he proceeds to unpack these phenomena, usually in such terms as “Asset urbanism needs to be understood in relation to both global and local parameters” or “Post-metropolitan islands are megadevelopments that are discrete and geographically separate.” In each instance, the illustrations are fairly compelling, while the explanations are a bit of a drudge—the more Soules tries to debunk these bizarre excrescences of the free market, the more they gain the upper hand. Milton did something similar for Satan.

As far back as Jameson’s celebrated account of the Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles, the spectacle of architecture under capitalism has always threatened to upstage any critic trying to take it down a peg. And Soules does not make life any easier for himself by taking on other, softer targets. Among the particular objects of his ire: Bjarke Ingels, the Danish designer who has become the preferred dunk-tank clown for a swath of the design commentariat. Comparing him to a “Houdini,” Icebergs skewers the Scandinavian for disguising his big-profit housing commissions as grandiose social-benefit schemes. Soules’s point here is well-taken; yet the now-widespread cult of Bjarke Bashing (full disclosure: I’ve taken a few shots myself) has grown somewhat tiresome. If bringing out the heavy theoretical artillery on more garishly soulless enterprises—the titular underground “iceberg” mansions of London, the never-completed housing tracts of Phoenix—results in the occasional backfire, the fusillades launched by Soules against a well-meaning if megalomaniacal technocrat like Ingels seem very much like overkill. Besides, haven’t we moved beyond Bjarke?

This approaches the issue over which the book, and with it a whole critical tendency, suffers the most. For one thing, as the decisions of the last four or so Pritzker Prize committees should have made plain, the professional solar system no longer revolves around marquee names hawking signature formal tropes. The Age of the Starchitect is behind us; collaborative and social-minded offices are now in the ascendancy. For all that Patrik Schumacher—who also comes in for a pasting from Soules—can still peddle parametrics to impressionable billionaires, he is yesterday’s man, and there is little to be gained from continuing to kick him, gratifying as it might feel at times. The discipline is in a very different place than it was ten years ago: for the design student as for the publicist, for the earnest online thought leader as for the cynical sloganeering developer, such things as technical innovation, philosophical import, or pure artistic aplomb—all evaluative criteria in good standing until fairly recently—now take a definite backseat to civic virtue. Yet you’d hardly know that to read Soules’s book, or indeed a great deal of other writing on contemporary architecture (even some very good writing).

So why doesn’t criticism get a new bag, training its sights on architecture’s budding normative mode? Here we come to the heart of the matter. Imagine for an instant that Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin were rewritten as, say, Shared Kitchens, Green Roofs, and the Half-a-House. In that case, the author would surely be obliged to point out the very real deficiencies and compromises intrinsic to even the most modest, most committed models of practice. This much could actually be pretty valuable—but again, if current trends hold, it is only too easy to see how this game might play out in the discourse at large. To some extent, it’s doing so right now: blowing the last bridges between design and anything smacking of “solutionism,” the critique starts to fold back on itself, collapsing into an impossibilism where everything that is good is bad; where architects and their buildings are devoid not just of autonomy (which, fair ’nuff) but of interest; and where criticism is reduced to the reflexive gainsaying of the latest press release or the latest tweet, rather than an attempt, as the late great Michael Sorkin once wrote, to figure out “how to simultaneously value artistic expression… and to rail against a world going to hell in a handbasket.”

From there—and this, too, is already in evidence—the only way out for critics is either to abandon their posts altogether or else embrace such dubious ideological contrivances as the belief that if architects and critics would but recognize their status as workers, they could click their heels three times and be back in Agency-ville. The latter proposition (really only a modified take on the operaismo popular in some architectural circles circa 1968) at least represents a kind of synthesis, a program worth (re)considering; Soules, at first, doesn’t appear to get that far, trapped in a repetition of learned tautologies, capitalist architecture a result of capitalism, et cetera ad nauseam. But right at the end, something amazing happens.

Clues to it appear early on, in particular through the author’s unusually clear-eyed discussions of some of the immensely complex financial machinery involved in the real estate biz. (One minor note: Soules states that investors are drawn to high-end condos, like those at Manhattan’s 432 Park, for their “liquidity.” The very appeal of those units is they never have to be “liquidated,” in the strict sense of a cash exchange; they can be sold for other assets of commensurate value.) In several instances, the author also name-checks Rem Koolhaas—not, as one might expect, to drag him for his globalist escapades, but to contrast the bustling “corporeal capitalism” of Koolhaas’s metropolitan ideal with the unpeopled abstraction of 432 Park, cleverly compared by Soules to Aldo Rossi’s Modena ossuary. And then, in a brief, remarkably personal epilogue, the author writes the following:

Architecture has long grappled with how to respond to the shortcomings of capitalism. But capitalism’s rapacious capacity to absorb all manner of attack is legendary. Because architecture is now finance, an effective critical architect must practice a form of critical finance. This doesn’t mean that architects should become bankers, but rather that architects might consider collaborating with financiers in a manner that is similar to how they currently work with engineers.

You read that right. Whether his exact prescription is sound or not, Soules winds up suggesting that there may be some “other” architecture out there after all—an architecture that neither plays patsy for Wall Street nor pretends to some ascetic political remove it can never really achieve. By implication, he also makes the case that to complement this oppositional yet nimble architecture, we need a criticism of like character, one capable of playing on all keys while eschewing both cynicism and credulity, or the one masquerading as the other. To perform Sorkin’s balancing act requires an anxious criticism and anxious critics. But it makes for a better show.

Ian Volner has contributed articles on architecture, design, and urbanism to The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Harper’s, Dwell, and The New Yorker online among other publications. His most recent book is Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography (Phaidon, 2020).

AN uses affiliate links. If you purchase something through one of the links provided, AN may receive a comission.