By definition, an oblique orientation or direction is neither parallel nor perpendicular to its reference but instead takes on an alternative angle. The French architect Claude Parent (1922–2016), whose drawings are on view at the Soho gallery a83 in a solo exhibition titled Oblique Narratives No. 1, devoted much of his prolific career to developing an alternative approach to architecture. Parent is best known for the oblique function, a theory of the inclined plane that he advanced in the 1960s as a leader of the Parisian interdisciplinary group Architecture Principe. According to Parent and his collaborators, sloped surfaces inspired people’s active engagement with the built environment, the anticipated grassroots-style effect of which was to be architecture’s renewed social relevance. (The late theorist Paul Virilio was the group’s other key figure.) By proposing to place all of life’s activities on the oblique, Architecture Principe envisioned the future of architecture free of not only orthogonal form but also of strict distinctions between program and circulation. The overarching aim, according to the group’s manifesto, was to emancipate both architecture and its inhabitants from the outdated orthodoxies of modernism.

While the group lasted for no more than a few years, the resulting theory had a persistent presence in Parent’s work and continues to be of interest to architects today. Oblique Narratives No. 1 provides convincing evidence of such endurance. Through nearly four dozen exquisitely crafted graphite-on-paper drawings, produced between the early 1980s and the mid-2000s, the exhibition shows how many of the conceptual and formal themes conceived in the 1960s continued to inform the architect’s imagination in the later stages of his practice. The show is tailored to an American audience—Parent’s work is not nearly as well-known in the U.S. as it is in his native France—as well as younger generations of architects, students, and art collectors (some of the drawings at a83 are for sale). While not everyone seeing the show will have already known this work, many if not most will be familiar with the contemporary architecture that it influenced, such as that of Jean Nouvel, Odile Decq, Bernard Tschumi, and Zaha Hadid. For those encountering Parent’s drawings for the first time, the intergenerational aesthetic resonances will almost certainly feel like a revelation.

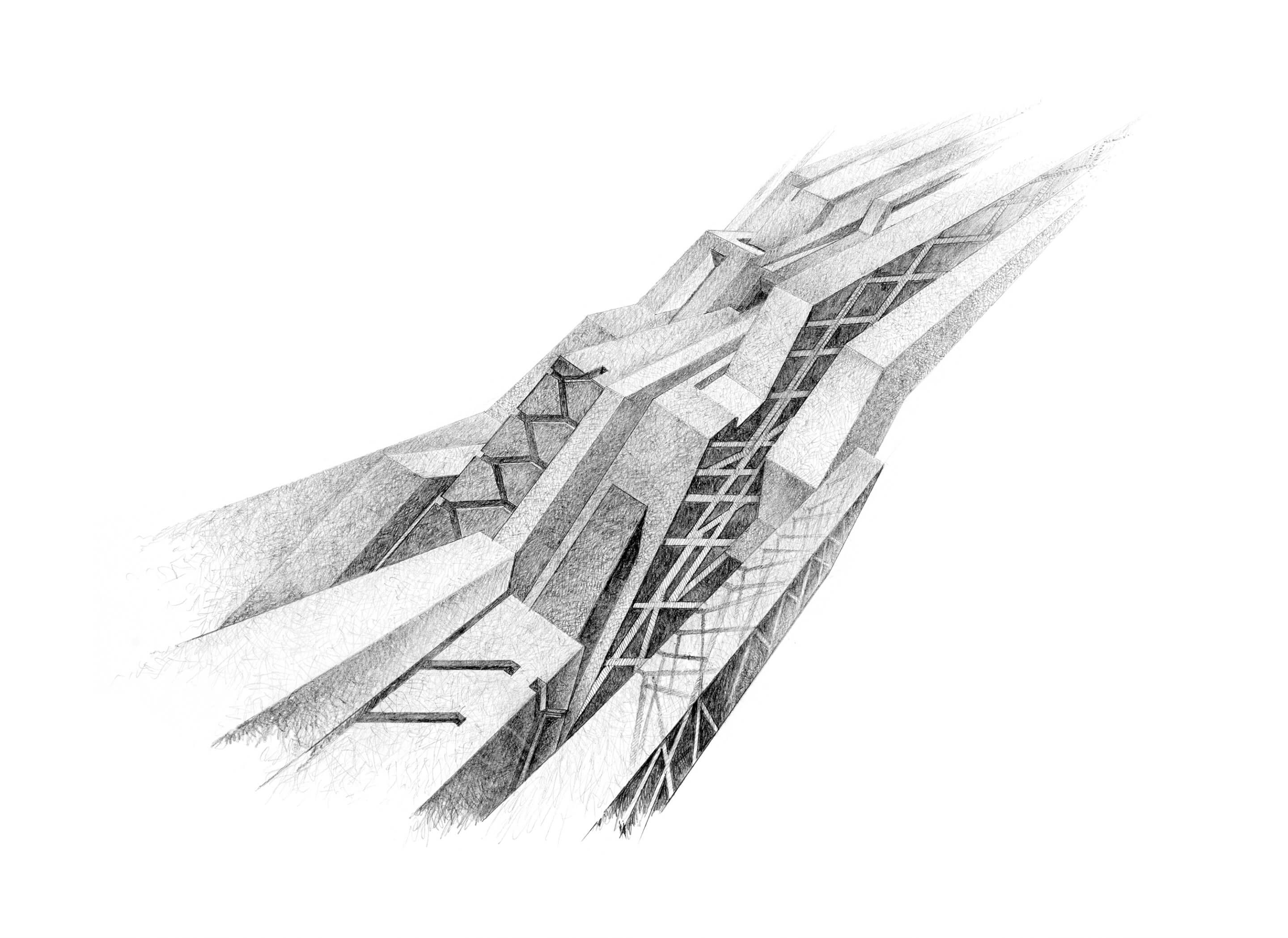

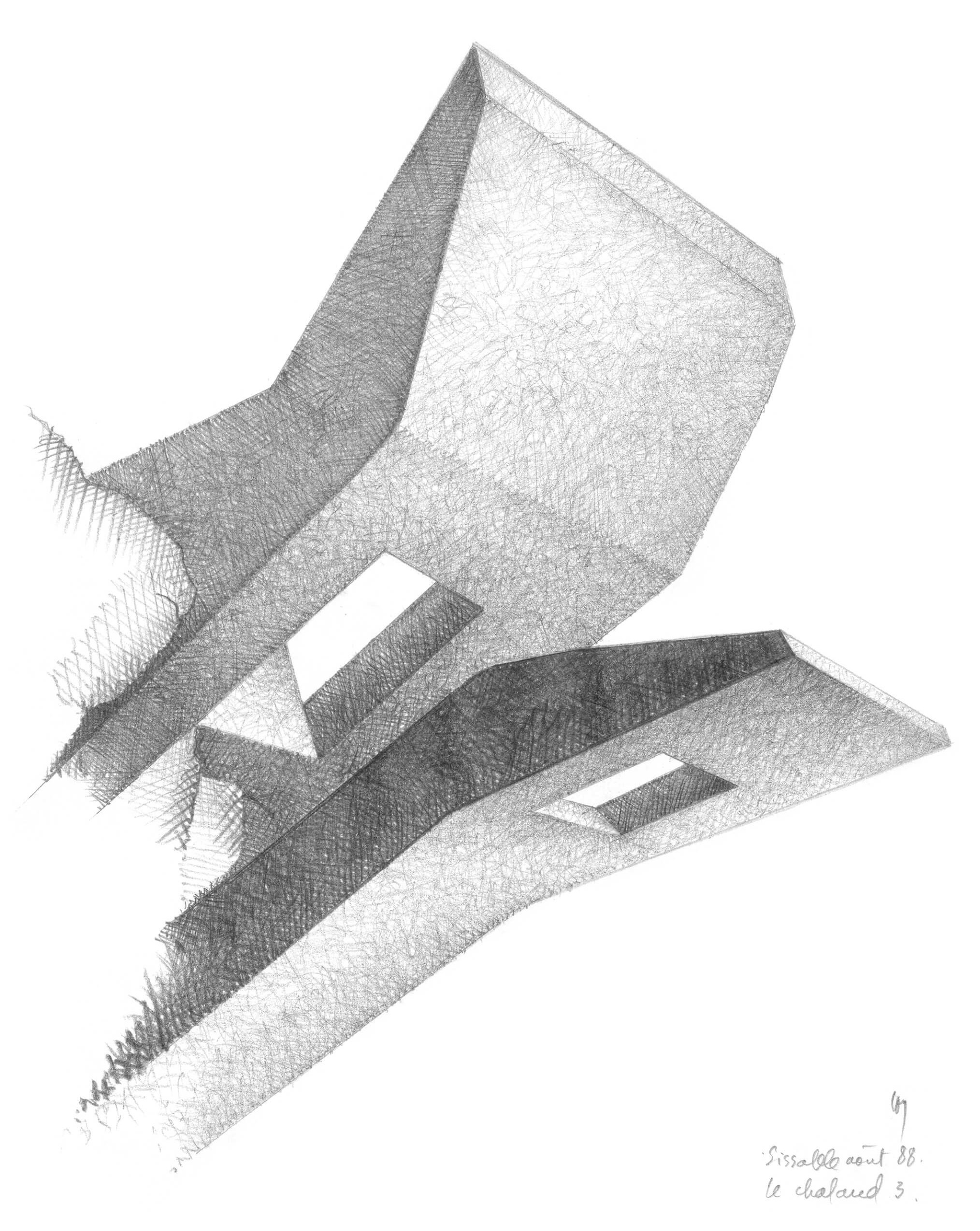

Rather than specific building proposals, the drawings included in Oblique Narratives No. 1 are of imagined objects, landscapes, and spaces whose abstract forms can be interpreted at multiple scales and without reference to any particular typology. Such architectures appear oblique both in geometry—a result of their tilting, folding, slanting, and tapering—as well as in their diagonal orientation on paper which, in turn, implies a sense of motion. Monolithic volumes twist and torque as if under the influence of some invisible force, such as those in the Chaland series. (The title offers the possible double meaning of both barge and client.) In some drawings, elongated strands—braided, bundled, and woven like a cable—resemble endless stretches of infrastructure vanishing into the distance. Parent also found inspiration in natural landscapes whose continuous topographies, once interpreted in his signature drawing style, emerge as oblique architecture in their own right. The drawings reiterate his preoccupation with the ground as a malleable architectural condition, while various references to the sea are suggestive of a fluidity that seemed to interest him.

Up close, bold forms yield to intricate textures: An array of freehand patterns converts precisely drafted flat outlines into three-dimensional volumes, and the varying densities of applied graphite distributes lightness and weight across each sheet of paper. This micro-riot of hatches and cross-hatches reveals the patience, commitment, and dexterity that is both out of place and entirely welcome in today’s world dominated by fast pixels and algorithms. Likewise, the squiggly Brillo-like marks, the outcome of a rendering technique known as scumbling, imbue even the most abstract of the oblique constructs with a sense of tactility and physical presence often absent from contemporary representations of architecture.

Parent’s drawing titles provide a constellation of external references, including to urban fabric, cities, houses, the Aegean Sea as well as places like the salt marshes of Sissable, where he and his family spent their summers. Each title offers a one-line origin story, more biographical rather than architectural. The autobiographical aspect of these drawings is further underscored by titles that reflect emotion, such as the Colère series from 1982, an apparently tumultuous period during which Parent drew a series of forms at a breaking point—colère, in French, means anger.

Oblique Narratives No. 1 is in this regard as much an abridged survey of the architect’s drawing practice as it is his portrait, whose display is designed to be discovered by each visitor in their own way. Eschewing conventional wall hanging, the show instead uses a cluster of flat file cabinets resting on metal sawhorses for the display. The result is a diagonal island-like configuration that compositionally mirrors many of the drawings, with the sliding cabinet doors and angled easels providing the kind of display landscape that Parent would have certainly preferred to the strict verticality of walls. Browsing through this mini-archive by opening and closing the drawers, getting as close to touching the drawings as one possibly could, and circulating around without a predetermined sequence makes for an exceptionally intimate encounter between the visitor and the architect’s oblique universe.

In the essay “The Hand that Draws,” included in the 2019 monograph Claude Parent: Visionary Architect published by Rizzoli, his daughter Chloé Parent writes, “While Architecture is his battle, Drawing is his serenity.” The statement confirms the affective and deeply personal nature of drawing in Parent’s career, but also serves as a reminder that this part of his practice was embedded within a much broader and remarkably diverse life as an architect. Indeed, from the 1950s on, Parent built quite a few houses and apartment buildings, several civic and commercial buildings, two nuclear power plants, and a famous church. Additionally, he collaborated with numerous artists; curated exhibitions; wrote for magazines; plastered the city of Paris, activist-style, with posters of his own design; and tirelessly promoted the virtues of the oblique function through participatory public programs which he toured all over France. Parent, in other words, practiced architecture in as many ways as he could in order to find alternatives to the status quo in both architectural practice and form. Given such a track record, his drawings are to be understood not as an outcome of an isolated, purist, or purely theoretical practice, but rather as a reflection of wisdom gained through a relentless engagement with the opportunities and obstacles of the external world. In today’s slang, architects might call this way of working a hustle, and as such some may find it inspiring that among Parent’s many side hustles, his drawing practice turned out to be a significant enterprise in the long run.

As the exhibit’s title promises, there will be a sequel. Following Oblique Narratives No. 1, a83 and the Claude Parent Archives are continuing their collaboration with plans to mount another show next year. The focus will likely be on specific projects from Parent’s practice as well as the influence of his ideas as seen in the work of other architects. Given the vast wealth of materials held by both non-profit organizations—along with serving as an exhibition space, a83 also maintains a significant print archive with items by some of the world’s most significant architects—this next installment promises to deliver another set of oblique revelations to its New York audience.

Claude Parent, Oblique Narratives No. 1

a83

83 Grand St, New York, NY 10013

Open through July 3

Igor Siddiqui is an architect and associate professor at The University of Texas School of Architecture in Austin. He is currently at work on a book manuscript titled Oblique Interiors: Ground Body Action.