I don’t know about you, but lately it’s easy for me to get demoralized. I wake up every morning and read about the hollowing out of the middle class in America, the near-constant acts of gun violence, the war in Ukraine, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, the existential threat of climate change. In my immediate circle, I hear from architecture friends about difficult renovations, legal conflicts, incomprehensible lawsuits, and the constant friction between people trying to live next to one another. Sometimes I imagine the only way forward is a life of isolation: Maybe I should remove myself from culture and find a cabin in the woods. Then I remember that not only do cabins in the woods have their problems, but that’s not the kind of life I want to live. Still, the individualism that pervades our society—the constant differentiation between you and me, where you’re coming from and where I’m coming from, and what you want and what I want—is not only a tough pill to swallow but one that feels like it’ll never change.

Amid thoughts like these, I was so heartened to spend time at Reset: Towards a New Commons, the current show at the Center for Architecture in New York. The exhibition opens with this declaration: “Contemporary American culture is increasingly disconnected, with people divided by needs, generations, and beliefs. The disconnection has been exacerbated by the enduring COVID-19 pandemic and illuminated by the growing racial justice movement. This exhibition will explore the belief that environments that foster cooperation, interaction, and mutual assistance can be an antidote to the intense divisions in American life.” The show, cocurated by Barry Bergdoll and Juliana Barton, stages four interventions by four teams of architects and designers to realize proposals that would “encourage new ways of living collaboratively while considering cross-generational living and designing for different abilities.” The interdisciplinary teams drew on a variety of approaches to community building as they engaged sites in Oakland, Cincinnati, New York City, and Berkeley.

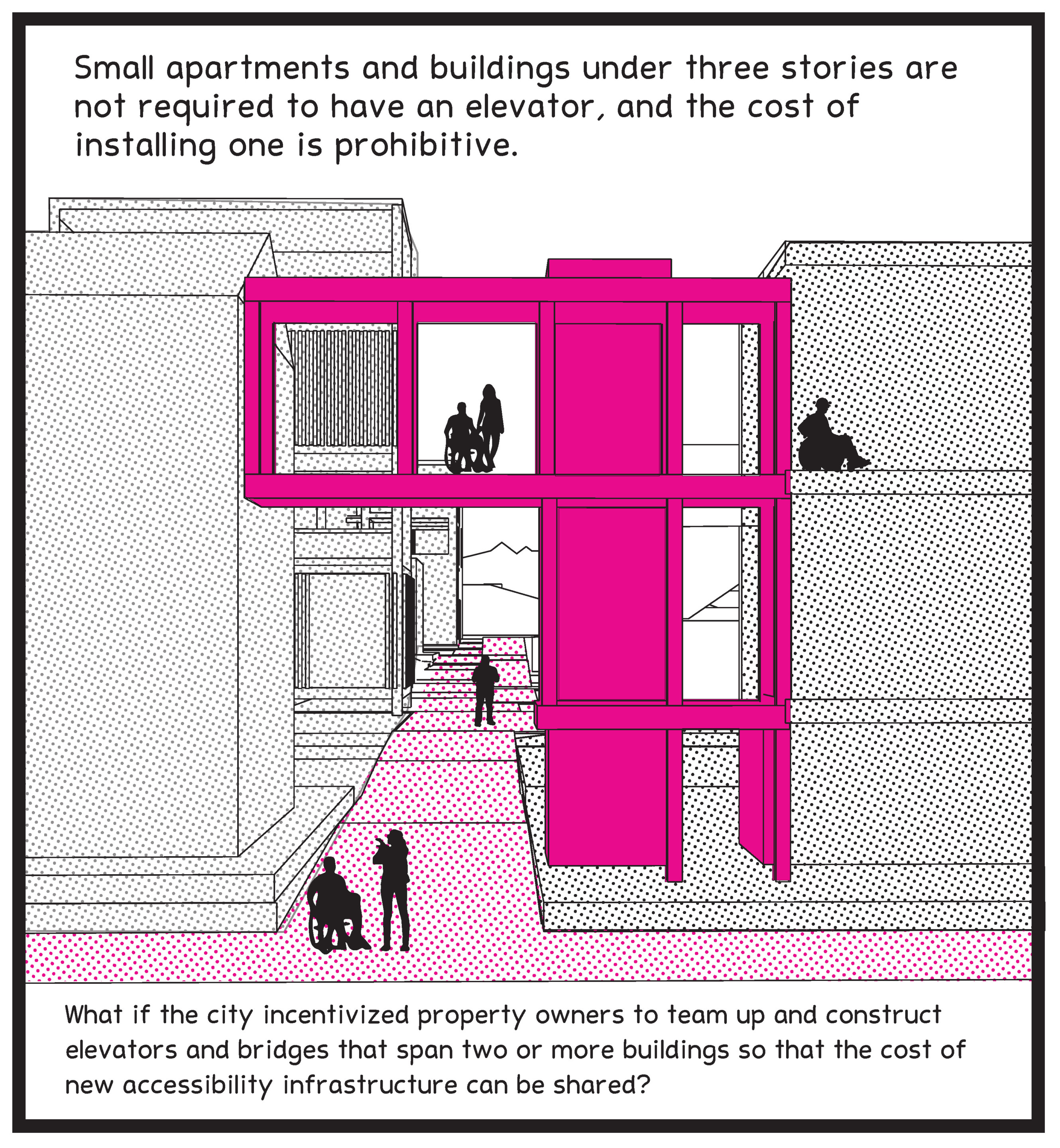

Each team staked out a specific method of engagement. In Berkeley, Block Party: From Independent Living to Disability Collectives draws together architectural historians, disability experts, and artists to explore new and more equitable ways of providing spaces for people of all abilities; in Cincinnati, Decolonizing Suburbia invites us to imagine a new world; in East Harlem, Re:Play Reclaiming the Commons through Play asks us to consider the role of joy and playfulness in the city center; and in Oakland, Aging Against the Machine makes a case for intergenerational living and spatial arrangements that support it.

Each effort is communicated through models, drawings, stories, recordings, and narratives. On the main floor of the Center for Architecture, two large models—one from Aging Against the Machine and one from Block Party—sit on plinths. The detailed former item showcases the potential of mixed-age housing, while the latter materializes a stretch of Berkeley as built (in wood) and as possible (hot pink pathways with 3D-printed ADUs). On the lower level, maps of Cincinnati hung on the wall work in concert with pieces of paper covered in handwritten suggestions from the East Harlem participants, demonstrating just how many forms these ideas can take. Seen together, they remind visitors that there are so many more people working on improving our civic life than there are trying to destroy it.

Decolonizing Suburbia, led by Andrew Bruno, Alessandro Orsini, William Prince, Nick Roseboro, Sharon Egretta Sutton, and John Vogt, aims to consider architecture and urban space as a communal rather than individual project. The effort focuses on Cincinnati’s Avondale neighborhood. The thrust here is one of reclaiming the idea of “the commons,” adapting vacant lots and transforming them into new housing opportunities, vibrant public spaces, and an opportunity for collective ownership.

In order to more directly address the needs of people with disabilities, Irene Cheng, David Gissen, and Brett Snyder led Block Party in collaboration with, among others, Javier Arbona and the disability scholar Georgina Kleege. Their proposal first analyzes typical approaches to supporting people with disabilities and then points out why elevators and single-story buildings are both less than ideal. Taking a single block on Prince Street in South Berkeley, the team proposes an intervention that weaves accessible housing into the existing infrastructure and models alternatives to the typical single-family-with-cars urban layout. The team’s proposal relies on the Berkeley City Council’s 2021 move to abolish single-family zoning and demonstrates the value of raised basements, garage conversions, and backyard cottages in both increasing housing stock and offering new typologies. The team asks: “Could these new forms of denser housing be harnessed to support multiracial disability communities engaged in mutual aid and communal flourishing?” It seems like they could.

In Re: Play, a collective effort led by Deborah Gans, five young resident designers who live on three New York City Housing Authority campuses offer sketches, ideas, drawings, plans, narratives, and ideals, many of which are displayed in a show of imagination and, unsurprisingly, play. I found this proposal incredibly moving and powerful, as it evidences the clarity and community orientation that so many younger people have. It reminded me that each generation seems to be more attuned, caring, and ultimately optimistic than the last.

I was most drawn to Aging Against the Machine, led by Karen Kubey, Ignacio G. Galan, and Neeraj Bhatia, probably because I spent a few years living on San Pablo Avenue in Berkeley and felt like their show captured the particular tensions of the East Bay. I recall the discordance between my life, in a typical luxury five-over-one construction, and that of the people who lived a few miles down the street, residents who had lived through transformations in West Oakland and were now trying to figure out how to make it work. On its northern end, closer to the UC Berkeley campus, San Pablo is a shaded street lined with delightful restaurants and patios. On its southern end, where Aging Against the Machine is sited, it’s a wide boulevard lined with mostly Victorian houses that have been either kept intact or split up into apartments for grad students or locals who’ve found themselves seeking more affordable housing. The project team takes as its starting point West Oakland’s combination of challenges—“precarious living conditions, insufficient public infrastructure[and] the legacies of redlining”—with the strong presence of community-based support, a desire to “resist predatory real estate practices,” and a consistent emphasis on helping each other.

The team’s recommendations, based on a series of conversations and roundtables with local residents and informed by what people who live there actually want, center on solutions from “interior home renovations to collective land ownership models and intergenerational housing projects.” Divided into seven scenes, the proposal includes recommendations for a street transformation that massively improves safety by building three medians; an honest expression of what intergenerational housing might look like (the scenario is a young UC Berkeley undergrad sharing an apartment with a longtime San Pablo resident, an arrangement that’s both “awkward” and productive); the introduction of new housing developments; and, my favorite, Shared Ramps, a proposal for installing a large porch that would span three houses, accessible via a ramp, inspired by a 1982 Center for Independent Living publication. The scene, as drawn and described here, is hypersocial: Children take turns serving dinner; wheelchair users navigate ramps to visit their friends and family; and people do each other’s hair. I loved it because it reminded me once again that sometimes social issues really can be addressed through a relatively simple and inexpensive spatial solution, an idea so often lost in the fog of politics, policy, and power.

Beyond its physical manifestation, Reset also crucially exists online, where it’s incredibly well organized, clear, and developed. I came away from my visit to the Center (and my later online experience) feeling like I’d been gently prompted to think deeply and generously about all the people whom I share space with, whether in close proximity or at the larger scales of neighborhood, city, and country. If you need a boost amid the larger tumult of today’s housing crisis and want to learn from examples of people thinking about helping each other—go see it for yourself.

Reset: Towards a New Commons runs through September 3, 2022 at the Center for Architecture in Manhattan. The digital exhibition can be viewed here.

Eva Hagberg is the author of How to Be Loved, a memoir, and the forthcoming When Eero Met His Match. She holds a PhD in visual and narrative culture from UC Berkeley and lives in Brooklyn.