In 2022 AN reviewed exhibitions, books, a play, and even the metaverse. From a review that argues women architects need more than books to advance in today’s world, to Robert Fiennes playing an angry Robert Moses on stage at The Shed, to Liberland—a metaverse designed by Zaha Hadid Architects—here is a selection of AN’s best reviews of 2022, a metareview if you will.

Patrik Schumacher’s Liberland Metaverse is pure cringe

AN contributor Ryan Scavnicky spent some time in the Liberland Metaverse, a digital world designed by Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) for Liberland Founder and President Vít Jedlička. Liberland is an as-yet-unrecognized and currently uninhabited micronation on the western bank of the Danube between Serbia and Croatia.

While strolling—or scrolling?—through the immersive digital environment built out on the Mytaverse platform, Scavnicky wrote that he couldn’t help but cringe.

The bet that ZHA is making—designing a metaverse space like a built project in order to anticipate the eventual built outcome—is dead on arrival because the building will never be as useful as its metaverse version. It locks the entire country into an aesthetic outcome that is predetermined and absolutely not, as it claims, decentralized. If parametricism/tectonism is so all-consuming, why is Schumacher the only one who is allowed to practice it?

In Chicago, American Framing exposed the nation’s long-concealed construction method

American Framing, an exhibition that first mounted at the Pavilion of the United States at the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale traveled to Chicago’s Wrightwood 659 gallery this year.

Anjulie Rao reviewed the show, curated by architects and professors Paul Andersen and Paul Preissner, which revisits the architecture of wood framing as a distinctly American tradition. It stages photographs and models within a three-story wood frame construction built out within the gallery space.

The photographs make up the bulk of the exhibition. Initially I was baffled that there was so little text except for the exhibition description. All the photographs are untitled; only the photographers’ bios are displayed. It felt like I was missing something, until I realized that American Framing isn’t about making wood framing “visible.” It’s about what is hidden.

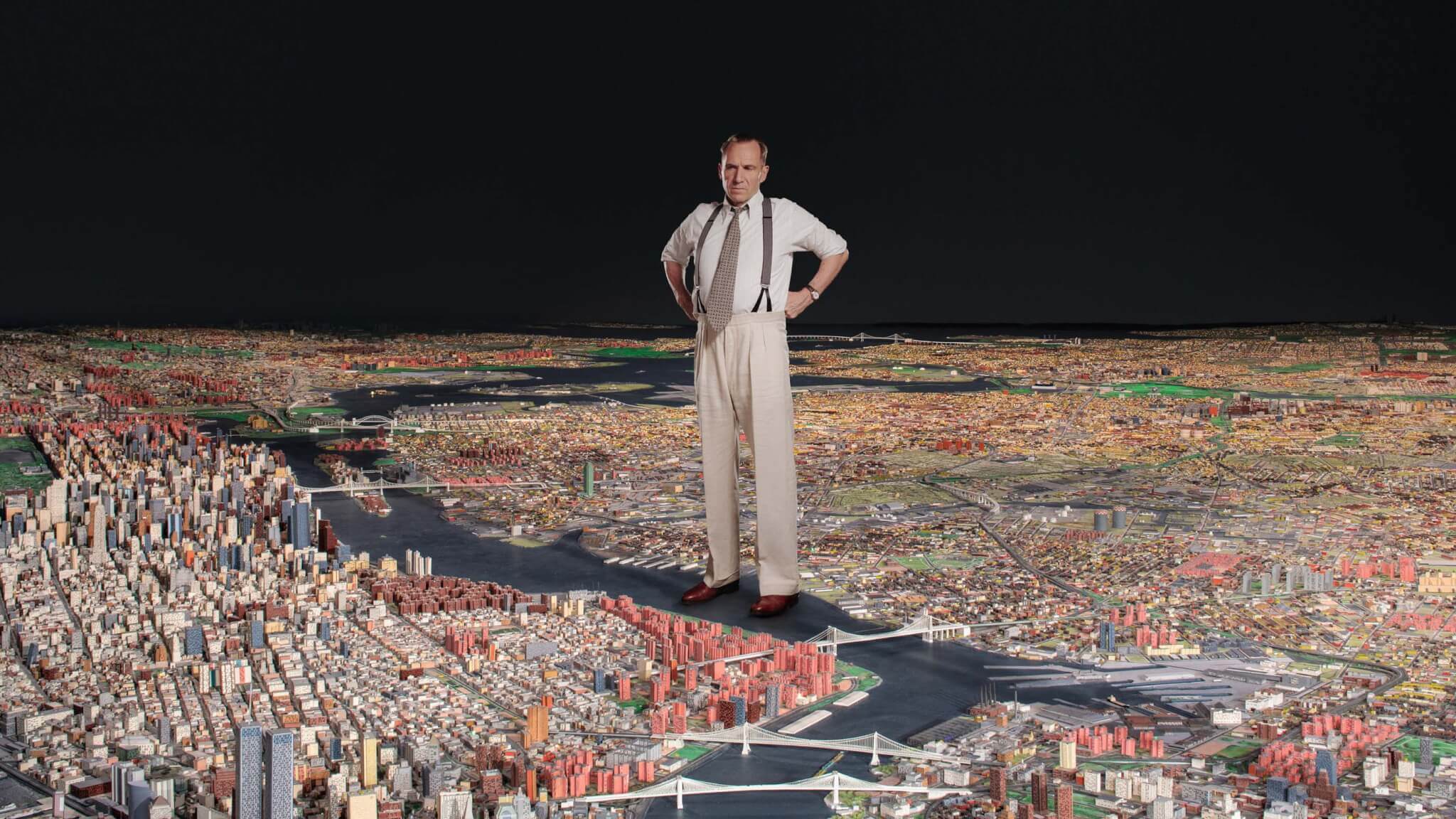

Ralph Fiennes plays an angry Robert Moses in Straight Line Crazy

This fall Straight Line Crazy, a play starring Robert Fiennes as Robert Moses in a dramatic retelling of the making of New York’s urban fabric, completely sold out at The Shed. Marianela D’Aprile snagged tickets and sat down for the 150-minute run of show, to watch a ruthless Moses “outwit, outmaneuver, and out-yell his detractors,” as he planned the construction of highways and roadways across New York City and its suburbs, resulting in a lesson about wrong morals and wrong interests.

If Fiennes seems possessed, it’s because Moses’s character is written by Hare not as someone might write a person but as they might write a demigod, someone whose motives and subsequent actions don’t stem from their material reality but from something else entirely, something ineffable, not earthly but earth-shaping. A cast of beautifully acted, earthbound characters, weak to Moses’s power, a gaggle of Davids teaming up not to defeat Goliath but to appease him, swarm around Fiennes’s Moses. They buzz and complain and argue, but their noisemaking is no match for Moses’s single-minded vision.

Chicago critic Blair Kamin’s Who is the City For? takes aim at aesthetic bungles while thornier issues go largely unaddressed

In a review of recently retired Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin’s book Who Is the City For? Architecture, Equity, and the Public Realm in Chicago, Zach Mortice takes issue with the text’s scope, laying claim that topics, such as race, go largely unaddressed.

The book, structured as a compilation of 55 of Kamin’s columns, examine the architecture and built environment of Chicago. One piece anthologized in the book “Signs Uglify Our Beautiful Bridges” tells the story of Bank of America (BoA) ads affixed to the Wabash Avenue Bridge, Kamin called the signs “a grotesque cheapening of the public realm.” Mortice takes aim at this piece in particular contending that it should do better to address BoA’s racist lending practices. The review goes on to consider the future of architecture criticism and the role the internet, particularly social media, plays in that discourse.

As the country’s stable of newspaper architecture critics gets put out to pasture, the sharpest critiques lately have come from digital-native content produced by terminally online and often-anonymous internet posters with none of the institutional heft of Kamin’s cohort and all of the sarcasm-laced, horny rage of overworked grad students.

Pier Paolo Tamburelli’s new book explores why Bramante’s work matters today

On Bramante by Pier Paolo Tamburelli presents readers with theoretical ideas, ideological provocations, close and often highly poetic readings of documents, but is less about Donato Bramante and his contributions to architecture and more of a “retroactive manifesto for architecture.” None the less, it is still a revisiting of Bramante’s work that makes clear why the work of the Italian architect and painter still matters today.

Readers are warned at the outset that what follows is not history or the kind of criticism offered by non-practitioners, but instead a book by an architect, about architecture, for the betterment of architecture. It is then, I would argue, a work of theory. The reader is further informed that theory in architecture is by and large the output of architects and that this discourse is more abundant in architecture than in other, more popular arts because architects have a greater need to reflect on the fundamental entanglements with power, money, labor, and politics that define their art more than any other; and theory aids this reflection.

For advancement in today’s world, women architects need more than books

This summer saw the Supreme Court overturn Roe vs. Wade, jeopardizing a woman’s right to make decisions about her own body. Two books published about women in architecture—The Women Who Changed Architecture and Expanding Field of Architecture further the discourse surrounding societal challenges presented to women, in particular those related to career.

The Women is divided into six chapters, each representing a different generation, it profiles the illustrious careers of dozens of women architects. On the other hand, Expanding Field focuses on the buildings more than the architects. In her review, Marianela D’Aprile argues the books could have done more to highlight the impact of women on architecture.

In terms of understanding the impact of women on architecture, I’d be more interested in, for example, a history of women’s organizations in architecture and design (Why did they get together and how did they do it? What problems did they cite and have any of them improved?) or a survey of the design of spaces used predominantly by women (nurseries, domestic violence shelters, single-sex schools, and gyms, to name a few). The majority of women who interact with buildings are not architects; there is more to be gleaned about the role of architecture in women’s lives—and about the impact of women on architecture—by looking at their experience.

The lives of subject and author unfold in parallel in Eva Hagberg’s intimate biography of Aline Louchheim Saarinen

When Eero Met His Match: Aline Louchheim Saarinen and the Making of an Architect by Eva Hagberg flips back and forth between the life and career of Aline Louchheim Saarinen—wife and public relations connoisseur of architect Eero Saarinen—and the life and career of the book’s author, who is also an architecture publicist and writer. It is simultaneously a biography and autobiography that chronicles the intimate history of Saarinen and his wife and details how her legacy made way for the architectural media landscape that exists today.

Hagberg delivers a serious thesis: Architects become known not just for their buildings but also for the stories told about those buildings. She argues that the highly literate and media-savvy Louchheim created narratives about Saarinen’s buildings that stuck. In a laborious parsing of media coverage of Saarinen’s work, she traces a direct line from language generated by Louchheim—in preparing Saarinen for interviews and in talking up his work to journalists—to the quantity and quality of coverage the architect received.

A new book about Lina Bo Bardi showcases recent engagements with the architect’s all-inclusive work

Lina Bo Bardi, an architect born in Italy who moved to Brazil, where she made career designing inclusive spaces integrated with nature is the subject of a new book. Lina Bo Bardi: Material Ideologies was published as the inaugural volume in the Princeton School of Architecture’s student-run Women in Design and Architecture (WDA) Publication Series and the result of the 2018 WDA Conference of the same name; it was edited by Princeton Dean Mónica Ponce de León and published by Princeton University Press and follows recent publications that have brought renewed international attention to Bo Bardi’s work.

The book highlights several projects by Bo Bardi, including her greatest civic project MASP and Casa de Vidro (Glass House), a property comprising several buildings that the architect used as a laboratory for testing design ideas.

Bo Bardi’s architecture was all-inclusive, open to animals and insects as well as to adults and children, but in particular it invited those typically excluded from elitist institutions. In her view, human life should always be the protagonist of architecture.

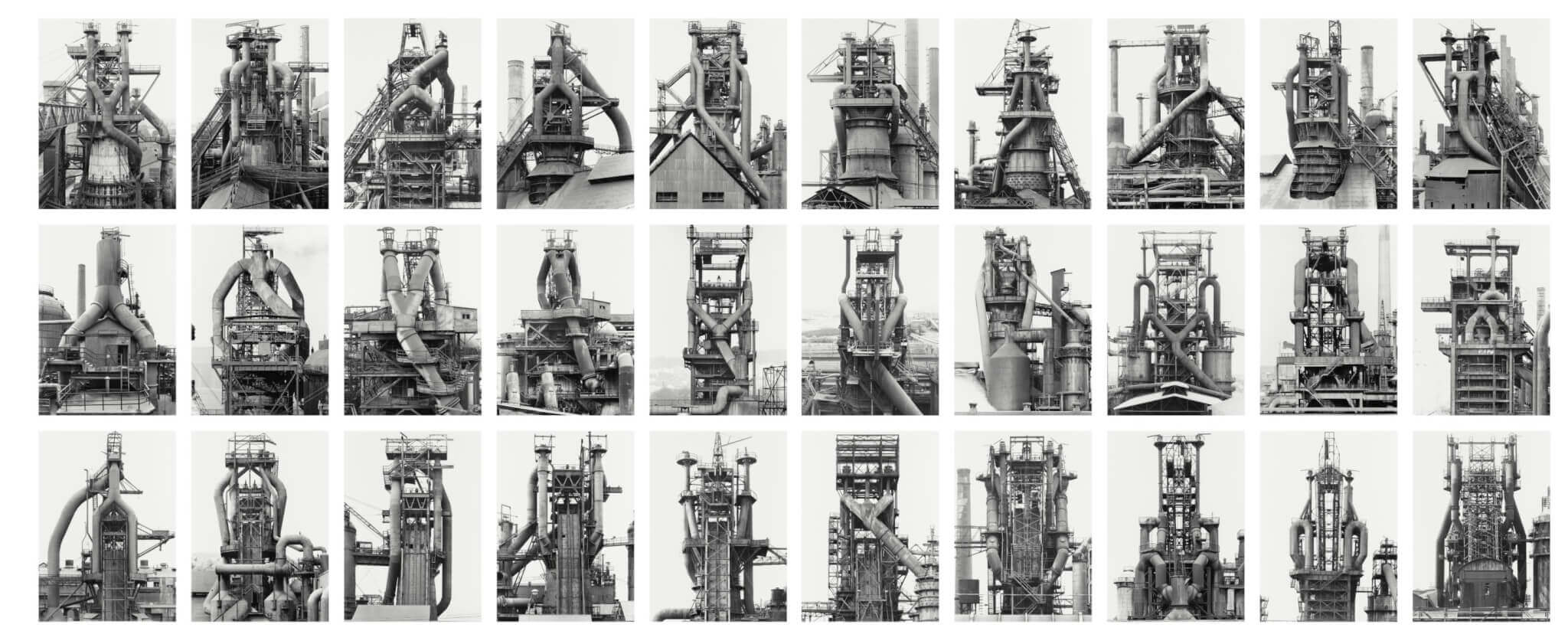

At the Met, the first posthumous show of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s photography showcased their influential oeuvre

The first posthumous retrospective of Bernd and Hilla Becher exhibited at The Met this fall. It chronicled the duo’s career from the mid-1960s through the early 2000s, resulting in a comprehensive archive of their black and white portraits documenting abandoned industrial sites in Western Europe and the United States.

Their abstract ruination evidences the global migration of industry; many of their subjects were demolished soon after having their portraits taken, suffusing them with an elegiac quality. The context establishes a postindustrial landscape in which, decades later, a new flavor of conservatism would come bubbling up like oil. The societal neglect that descended following the Bechers’ exposures—that palpable feeling of “being abandoned” known to anyone living in the Rust Belt or South Westphalia—would prove to be a powerful psychological force that has found in politics an outlet for expression.