Lebbeus Woods, Ecologies, 1984-1990

Curated by Jennifer Olshin

Friedman Benda

8260 Marmont Lane

Los Angeles, CA 90069

Open through February 4

Lebbeus Woods died at his home in New York City on October 30, 2012. It was the same night that remnants of Hurricane Sandy flooded the streets of Lower Manhattan—where Woods lived—with 80 mph tropical winds and a powerful Atlantic storm surge. Dry land transformed into seabed, a city of glass towers resembling a reef: This urban conversion would not have been out of place in Woods’s own work. A prolific artist, writer, teacher, and architect, Woods left behind a voluminous personal archive of drawings, models, and essays, all of which reframed architecture not as an aesthetic pursuit, but as a radical act of philosophical, literary, and scientific, even cosmic, speculation.

Lebbeus Woods, Ecologies, 1984-1990, now on view in L.A.’s Hollywood Hills, brings together pencil and ink drawings on paper, vellum, and board from three of Woods’s mid-career projects. (A preview PDF gives a sense of the inventory.) These include a 1988 work known as Solohouse; rejected concept art for what would later become the 1992 science fiction film Alien 3; and, the most straightforwardly architectural of the group, Epicyclarium, produced from 1984 to 1985.

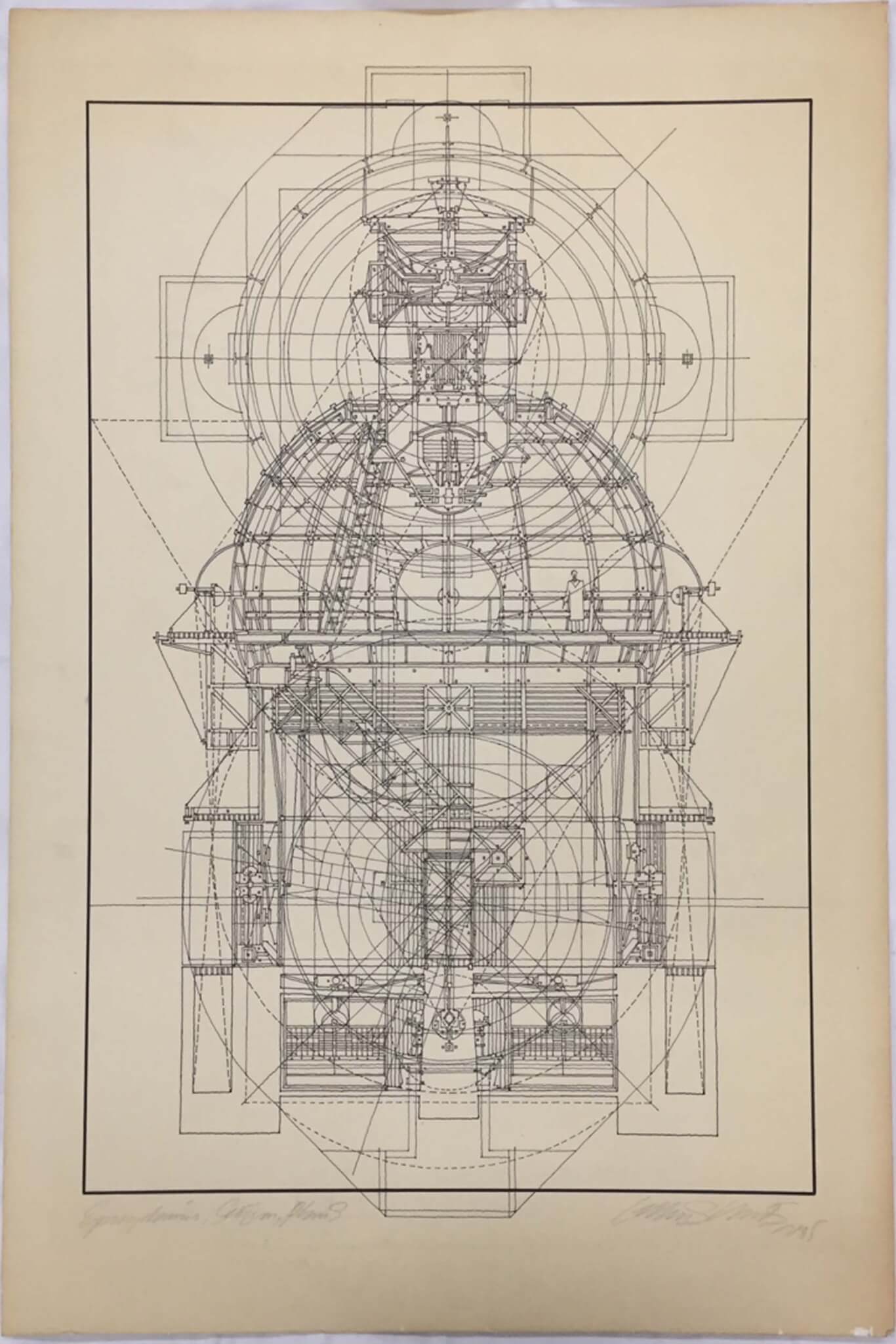

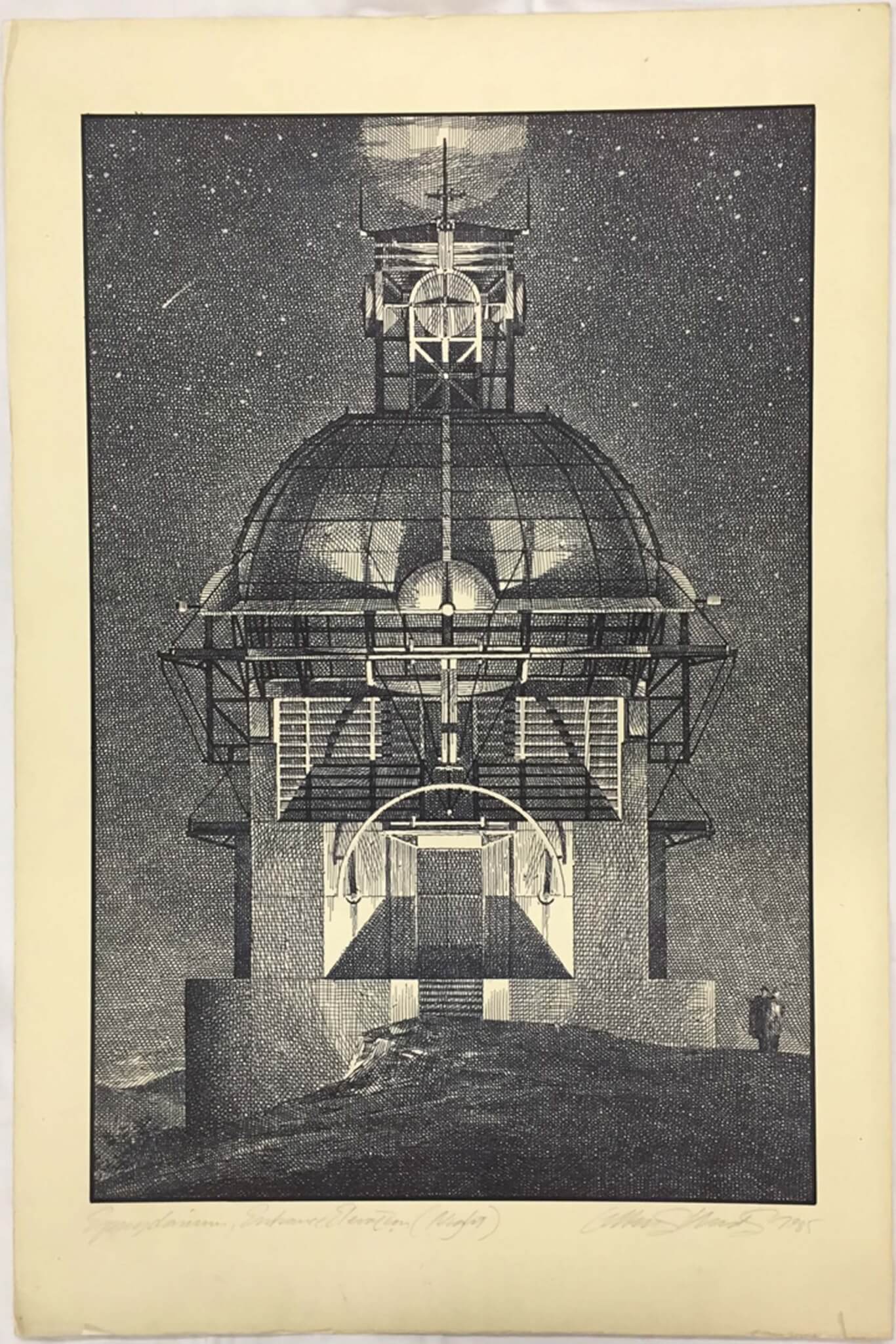

This last series proposed a new kind of scientific institution, one that would function equally as planetarium and laboratory—an epicyclarium in Woods’s coinage, or a facility for studying the convulsive cycles of energy and matter that structure the cosmos. In several of the drawings on display here, shadowy human figures can be seen outside the main entry door, implying both character and plot, and, in the process, revealing Woods’s long-term interest in narrative as a tool for architectural exploration. In one such image, two individuals—scientists, designers, pilgrims, or congregants, perhaps; they are all related in Woods’s mythology—converse. One holds an abstract scientific instrument whose form repeats many of the design gestures of the building that looms behind them. It is the physics lab as Gesamtkunstwerk.

The purpose of that building—a meticulously designed postmodern folly perched atop a hill—recalls Sir Francis Bacon’s fictional Salomon’s House, a philosophical meeting hall proposed in Bacon’s 1627 book New Atlantis, where obscure scientific tools would be designed, assembled, and displayed. The carefully measured plans of the building itself suggest a mandala—a kind of Buddhist spiritual chart—complete with nested circles, a symmetrical layout, and implied cosmic symbolism. Are these esoteric religious diagrams or eerily beautiful construction documents?

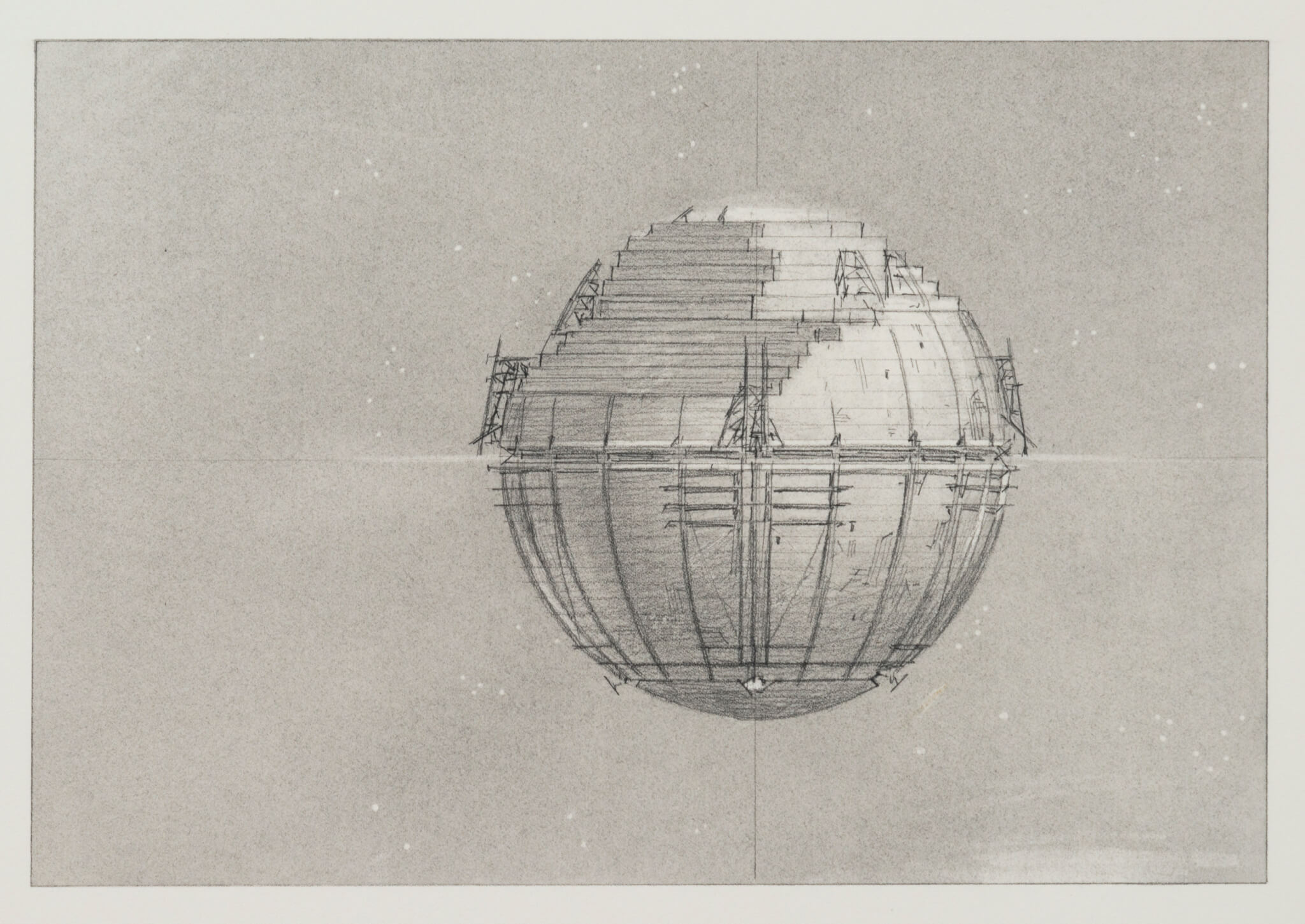

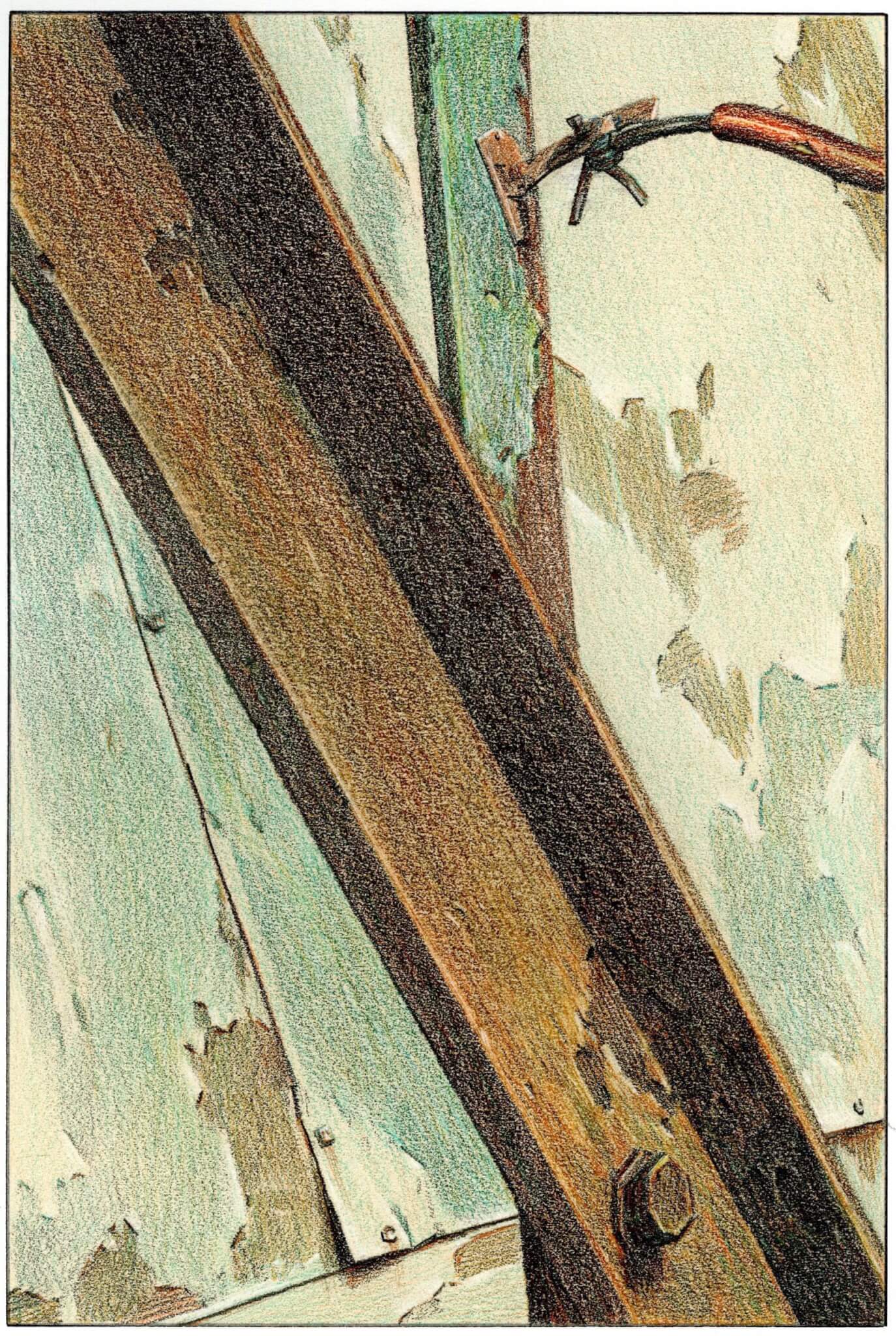

This interpretive confusion is at the core of much of Woods’s work. Although the drawings are displayed in a minor corridor of the gallery, Woods’s rejected set-designs for Alien 3 are both visually and philosophically striking. For that film, Woods proposed an artificial planet, made primarily from timber, to be used by its inhabitants as a monastery for spiritual and scientific reflection. The images themselves, complete with cathedral-like vaults and titanic cross-beams, are often organized like panels in a graphic novel—hardly surprising for a project designed for Hollywood, but a notable deviation from standard architectural illustration at the time of the project’s creation.

For Woods, architecture was always a means of orienting ourselves within unstable environmental conditions, from floods and war zones to earthquakes and interstellar space—a tool of survival for situating humanity in unusual, even hostile, spaces. In both the visions for Alien 3 and Woods’s arguably best-known work, Einstein Tomb (1980), this meant divorcing architecture from solid ground altogether, from the very idea of a planet. This approach was motivated not by an interest in science fiction for its own sake, but in trying to discover a space for ourselves founded literally on nothing—no home, no foundation, no land, just structure and refuge amidst pressure and immensity. That, for Woods, was architecture’s philosophical goal.

Although his epicyclarium was never built and this particular version of Alien 3 never realized, Woods’s renderings of what could have been are tantalizing for what they allow visitors to imagine: a different Hollywood, at the very least; a different architecture, if we can be more ambitious; but also a different way of understanding our species’ place in the cosmos, even if we are unsure where that investigation will ultimately lead.

Geoff Manaugh is a Los Angeles–based writer on architecture, design, and technology.