Vitruvius Without Text: The Biography of a Book

André Tavares | gta Verlag | €26

All arts and crafts have a history, and histories must start somewhere. Around the end of the Middle Ages scholars of ancient literature—first in some Italian cities— began ruminating on the idea that architecture was born on the shores of Greece and Italy (and not in the ancient Near East, as the Bible claims); they also concluded that Greek and Roman architecture built during the age we now call classical was the best of all time, which in turn prompted architects to imitate it—or “revive” it, as they claimed. This was the beginning of the classical tradition that has since held sway over the architecture of Christian Europe, with some interruptions, almost to the present day—in Europe and elsewhere. When Renaissance humanists started their studies of antiquity, they stumbled on a book on architecture written around the end of the first century BCE by someone named Vitruvius—apparently a military engineer—and they thought that book could help them understand and relearn the ancient way of building, of which nothing was known beyond what could be elicited from a paltry corpus of muted ancient monuments, often ruined beyond recognition.

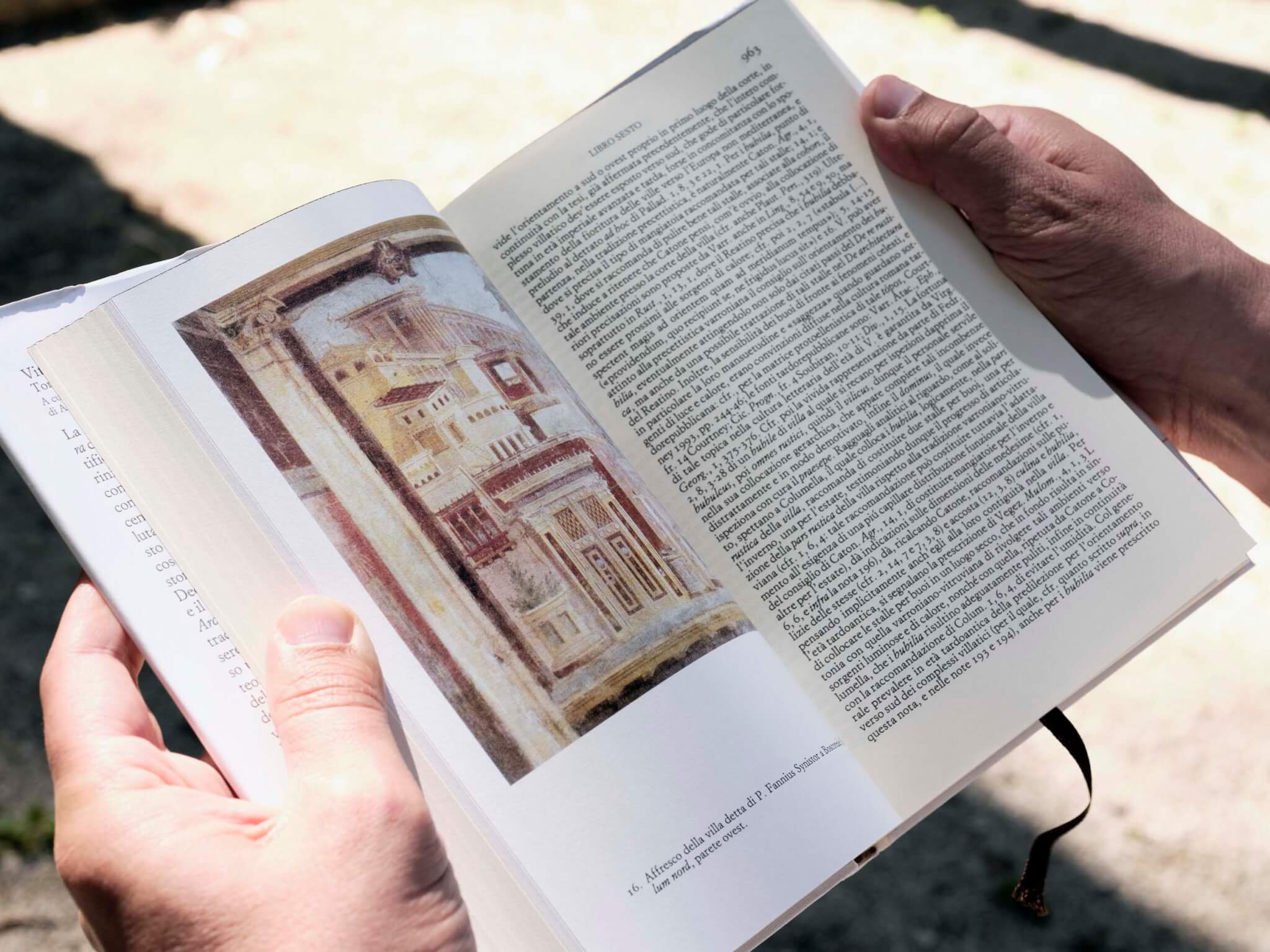

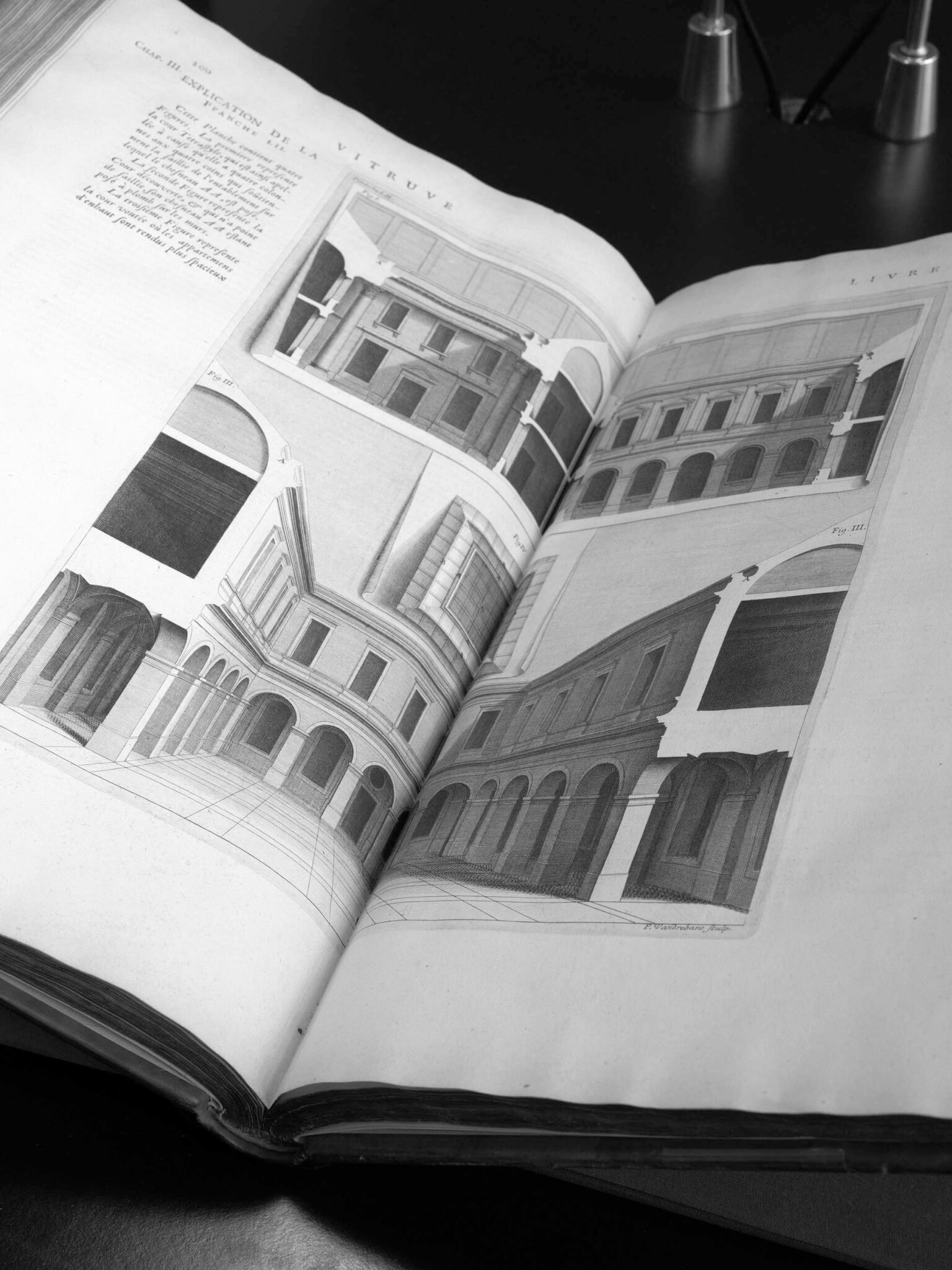

They soon found out that Vitruvius’s text, born at a time when books were laboriously handwritten on papyrus rolls, wasn’t exactly a technical manual. Roman builders of Vitruvius’s time learned their trade on the job, not from books, so it’s hard to tell for whom Vitruvius originally wrote; to this day, his is the only known treatise on architecture from classical antiquity, which suggests that when Vitruvius dedicated it to the first Roman emperor, Augustus—also his employer—his ten volumina would have had few competitors on the manuscript market. To make things worse for our Renaissance humanists, we now know—but they didn’t—that Vitruvius collated snippets from Hellenistic sources describing a way of building that was already archaic, and out of use, in his own time. All the same, copies of Vitruvius’s manuscript survived somehow throughout the Middle Ages, and when the humanists started to study it, they subjected Vitruvius’s text to the usual stages of modern scholarly appropriation: philological analysis (what did Vitruvius really write?), exegesis (what did he mean?), hermeneutics (what does that mean to us?). The first step required critical editions; the second and third, commentaries and illustrations. Images in particular were challenging, as Vitruvius’s text, like all scientific and technical treatises of classical antiquity, was only scantly illustrated. All original pictures being lost, modern interpreters had to add pictures to a text that didn’t have any, to illustrate buildings that, in most cases, nobody in the 16th century had ever seen—and most interpreters of the time could not even remotely figure out. Not surprisingly, this feedback loop between old text (often corrupted and obscure) and new images (often made up) produced over time some curious results; yet this is how, faute de mieux, Vitruvius’s book soon became “the Bible of Western Architects,” endlessly reprinted, translated, illustrated, interpreted, excerpted, and commented upon: the backbone of the European classical tradition in architecture, of which Vitruvianism came to be seen as a synonym.

Vitruvius’s first edition in print was in 1486 (or 1487), and by 1909 the German historian (and castle builder) Bodo Ebhardt could count around 100 (including translations, epitomes, and reprints); in 1978 the Vitruvian catalogue compiled under the direction of the Italian academician Luigi Vagnetti featured 166 editions, with brief descriptions of each. André Tavares, under the auspices of the Institute of Theory and History of Architecture of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), now publishes in this book a bibliography of 283 Vitruvian titles, from 1486 to 2016, alongside a history of Vitruvian editions in print, which is particularly valuable as it adds a few items published in the 1930s and 1940s that Vagnetti had, perhaps not accidentally, overlooked; Tavares also covers and contextualizes the wave of Vitruvian titles that followed the rise of postmodernism and the concomitant revival of interest in the classical tradition, and reviews recent Vitruvian studies of architectural interest.

This clarification is important as Vitruvius, as an encyclopedia of ancient arts and sciences, has been perused at length by art historians, architectural historians, antiquarians, and archaeologists; but it also contains important sources for the history of cities, of ancient medicine, of meteorology, of building materials and building techniques, of ancient building types, domestic and public; of music and musicology, of the theory of proportions, husbandry, hydraulics, astronomy, sundials, mechanical clocks, geometry, automata, poliorcetics, military machines, and more. But when architects— past and present—read Vitruvius, they tend to do so in their own special way. Of this Tavares offers a vivid historiographic illustration, showing how Vitruvius’s brief mention of a certain layout of courtyards in ancient Roman houses (De Architectura, VI,III,1, on tetrastyla cava aedium: internal courtyards in Roman houses with columns at the four corners of the impluvium), frequently misunderstood by modern interpreters, became the source of never-ending interpretive quandaries, of which traces can be found in tetrastyle halls of all sorts built around the world from the 16th century on, ranging from Palladio’s Vicentine palazzi to Corb’s Villa Stein, a Roman bath by Schinkel, a subway station from the late 1920s in Berlin, a 1946 coffeehouse in Tomar, Portugal, and Reichlin and Reinhart’s 1974 Casa Tonini near Lugano, Switzerland—some of these Vitruvian allusions being deliberate, some not. As Tavares thoughtfully concludes, the persistence of the tetrastyle design pattern highlights “the shared space of formal imagination,” where design patterns become “mnemonic or reminiscent forms,” regardless of context and use.

This, Tavares does not need to add, is what the classical tradition in architecture is all about. Tradition, after all, means “transmission,” and the core principle of the classical tradition is that some architectural forms or patterns can travel across space and time, and when they show up, even in the most incongruous settings, they signify to all familiar with their history the tradition to which they belong, and the allegiance to that tradition of those who chose those forms to put them where they stand. Similar modes of signification and recognition apply, of course, to most buildings, as all ways of building become at some point, if they endure, the tradition of some places or people; but when this memorative function is invoked in the name of the classical tradition, and explicitly theorized and posited as a matter of principle, we must stop and ask some difficult questions.

For the classical tradition is not the tradition of just any place; it is the core architectural tradition of Christian Europe, and Europe is the continent that, beginning right around the time when the idea of the classical tradition was taking shape, took over by force, and ruled over, militarily or economically, many other parts of the world. Hence the classical tradition is seen and resented in many parts of the world as a sign of the presence of colonial masters, postcolonial landlords, or foreign occupiers. Architectural historians might object that colonial powers didn’t always choose classicism to manifest their presence in foreign lands—other styles, such as Gothic, Romanesque, or national styles, were also occasionally used; the Italians in Eritrea even chose modernism to represent Fascist colonial rule. Yet classicism was in most cases the default option.

Likewise, the association of the classical tradition to one branch of Christianism in particular—the Roman Catholic—is a recent, postmodern aberration. When the Reformation came, the idea that architecture depended on the written authority of one book (the Architect’s Bible!) found a more sympathetic audience in the Protestant North than in the Catholic South, and rule-based Vitruvian classicism in particular became a puritan version of the classical language of architecture favored by early modern Evangelicals as a reaction against the baroque grandiloquence of counterreformation papacy. Last but not least, the classical tradition was the architectural language of choice of Enlightenment atheists (during the French Revolution, for example), and from the very start (in Florence circa 1430), but more strongly as of the late 18th century, classical architecture was also seen as a symbol of the republican democracy of Greek cities—alongside its long-standing association with Roman despotism and imperial power.

For all this, the classical tradition in architecture appears to have always had a particularly strong appeal to unsavory characters of all kinds—war criminals, dictators, white supremacists, or just plain and simple authoritarian, totalitarian, or centralized political systems. These notorious connotations are often taken for granted today—they are nevertheless puzzling. Why did so many bad guys—and some of the worst political institutions and associations in human history—develop such a liking for classical architecture? Is there something inherently wrong, possibly criminal, inscribed in the DNA, so to speak, of the classical tradition in architecture? The way architects have used Vitruvius for the last few centuries—from the end of the quarrel of the ancients and the moderns in the 17th century to the present—may suggest an answer.

Medical doctors today are well familiar with the medical science of Hippocrates, or Galen; they still study it at school, but they don’t use it to treat their patients. Many engineers today are fascinated by the machines that Heron of Alexandria designed and built around Vitruvius’s time, but they don’t follow Heron’s science to design electric cars. Architects are unique among all modern professionals in thinking that some theories from classical antiquity may still be of direct and practical use today—for example, that Vitruvius’s rules on the proportion of Doric temples may serve to design social housing, or an airport. That may appear to outsiders as a view somewhat devoid of common sense, yet architects believe in it for a reason, derived in turn from a universalist ideology that is deeply rooted in many Western philosophies. Even if they do not always say so in so many words, some classicist architects are more or less intimately persuaded that some Vitruvian rules—some rules of the classical tradition in architecture—are timeless and universal: valid across space and time. But if you believe that your ways are always good, and good for all, you may also easily conclude that your ways are the best, and everyone else’s are wrong and may deserve little respect.

This is where an architectural tradition becomes the assertion of the supremacy of one cultural tradition against all others; this is where the history of European architecture becomes the proclamation of a Eurocentric view of world architecture. We see what that means in daily life. If that is your worldview, all your buildings become ideological frontier posts: totemic indexes and flag bearers for the tribes that surround them. They mean to all that see them: We are the people of this place; this is what we are; this is where we come from; this is how we build. If you are not one of us, go elsewhere. In a world that is now painfully, and laboriously, trying to coalesce around some basic human principles of equality, diversity, and inclusion, classical architecture is thus at risk of becoming the emblem of all who stand for the opposite, and the rallying cry for many self-styled “anti-woke” reactionaries: Classical architecture was for example mandated for federal buildings by an executive order of former U.S. president Trump in the final days of his administration; the classical tradition in architecture was likewise recommended in 2020 by an official U.K. government commission on building, and the same principles have been more recently endorsed and reiterated by U.K. housing secretary Michael Gove. Let me be clear: André Tavares’s book is sound scholarly work (although I have found a few marginal errors here and there, and I have reservations on some historiographical issues, as is to be expected), and we should be grateful to him and to the ETH in Zurich for this publication. But let’s all be aware of what is at stake here. As Tavares concludes: “To possess a physical copy of Vitruvius, regardless of whether one reads it or not, is to possess an idea evocative of architecture’s cultural background, of its long-standing sources, and of the value of order and proportion.” As Vitruvius would have said, caveat emptor.

Mario Carpo is the Reyner Banham Professor of Architectural History at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London and professor of architectural theory at the University of Applied Arts (die Angewandte) in Vienna. His latest book, Beyond Digital: Design and Automation at the End of Modernity, was published by the MIT Press in April.