The alignment of Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU) with the ASTM/HOK team designing a new plan for Penn Station, announced on April 17, has moved that group’s plan toward the front of the pack, among some advocates, of the proposals to upgrade the region’s most troubled transit node. It has not sliced through a Gordian knot of intertwined controversies. Proponents of alternative plans argue that New York deserves a station every bit as ennobling as the one we lost, and that only the removal of Madison Square Garden (MSG) to a new location will make that possible.

Whatever scheme replaces Empire State Development (ESD)’s General Project Plan (GPP), considered as good as doomed, will need to resolve questions over rail operations, the public’s demand for world-class infrastructure, and the future of MSG. Complicating this debate are the related questions of Penn Station’s capacity expansion (perhaps adding the controversial Penn South, which would replace Block 780 between 30th and 31st Streets and Seventh and Eighth Avenues) and the adoption of through-running service—converting Penn from a terminal, where trains must reverse direction, to a more efficient bidirectional station with shorter train dwell times—a term that two major civic groups, ReThinkNYC and the Regional Plan Association (RPA), agree on in principle but vigorously disagree on in details. With Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) head Janno Lieber recently expressing skepticism about the ASTM/HOK/PAU plan, synchrony among the rail entities involved presents another challenge. The MTA and the other affected railroads (Amtrak and New Jersey Transit), however, have issued a report finding that MSG and Penn Station were no longer compatible, calling for major structural alterations if the arena is to stay in place.

The GPP has foundered on the shoals of both the perceived public interest—including charges that it was a giveaway to a political donor—and business conditions. Last year, the watchdog group Penn Community Defense Fund (PCDF), the City Club of New York, ReThinkNYC, and residents of 251 West 30th Street filed a suit challenging the GPP, supported by an amicus brief filed by the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the Preservation League of New York State. Good-government activism received an unexpected boost from the real estate market when Vornado Realty Trust, a potential beneficiary of the GPP’s plan to erect ten office buildings that would have contributed payments in lieu of taxes, halted its involvement in February in the face of high interest rates and low commercial demand. Although at this writing Governor Kathy Hochul has not formally abandoned the GPP, a pet project of her predecessor Andrew Cuomo, Vornado’s reluctance to proceed makes it a moot point. The “147 Bold Initiatives” in Hochul’s January 10 State-of-the-State agenda omit the GPP entirely.

One elected official involved in the approval process, State Senator Leroy Comrie (majority representative on the Public Authorities Control Board), told a joint public hearing on March 3 that the GPP was “a ridiculous plan, which we already know is dead three different ways, because beyond Vornado saying that they’re no longer interested, Senator Schumer said he’s no longer interested; Congressman Nadler said it doesn’t work. So let’s get with it already; we’re going to lose that opportunity to get those federal dollars” (under President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law).

The ASTM/HOK/PAU plan, unlike competing proposals by ReThink Penn Station (like ReThinkNYC, a project of planner/entrepreneur James Venturi’s ReThink Studio) and the Grand Penn Community Alliance (GPCA), leaves MSG in place, a feature that some but not all stakeholders see enhancing its feasibility. “We continue to believe that leaving Madison Square Garden on top of Penn Station while billions are spent on this project is to opt for mediocrity and compromise when the city, state and region deserve so much more,” said Samuel Turvey, chairperson of ReThinkNYC. “ReThinkNYC believes its proposal to build an aboveground station modeled after the original McKim, Mead & White version would have the greatest brand impact and corresponding economic benefits to New York. During such a station’s construction, the media coverage throughout the world would be creating five generations of rabid tourist appetites to visit New York and see the station.” Considering how a world-class experience for commuters would make the city more attractive to employers, Turvey added, “a rebuilt original Penn Station will pay for itself many times over in its impact on this entire region.”

Manhattan Community Board 5, which represents the district including the Penn/MSG superblock, has recommended letting MSG’s special operating permit expire in July, in hopes that this will force the arena to move. Madison Square Garden Entertainment (MSGE) insists that it is going nowhere, arguing that its next permit, unlike the 10-year extension it received in 2013, should be in perpetuity.

Another wild card is the prospect that a new MSG could be both architecturally distinguished and lucrative enough to convince MSGE’s leadership—possibly even its famously impulsive CEO James Dolan—that they’d be better off moving after all. ReThink supports Atelier & Co. principal Richard Cameron’s design for a neo–McKim, Mead & White station (largely replicating the original while adding contemporary materials and code compliance, Cameron suggests, including green roofs and solar and geothermal power). Although he serves as ReThink’s architectural advisor, Cameron’s personal vision goes further than the group’s in certain respects, viewing the station as part of a broader neighborhood upgrade including not only his designs for a new MSG—amounting to a running start offered to the very organization seen as a large part of the problem—but a new park and other public facilities. He is one of several observers convinced that MSG’s long-range future lies at a new site, regardless of how remote that scenario appears at the moment.

The Corporate-Citizenship Context

The 1968 iteration of the Garden is the oldest facility in the National Basketball Association and one of the oldest in the National Hockey League. Those impatient with MSG’s current position also point to its history, particularly the ongoing property tax break MSG received in the early 1980s amid hints of moving the teams out of Manhattan, a hardball tactic now considered inconceivable, along with directly contradicting Dolan and colleagues’ expressed intent to remain in place. Other forms of hardball, however, can be expected.

State Senator Brad Hoylman-Sigal (D-47th District, representing Manhattan’s West Side) contends that the city’s dealings with MSG have served the public poorly and opposes the GPP. “I’m fighting for Madison Square Garden to pay for its share of property taxes,” he told AN. “It owes New York City $41 million or more a year in property taxes that it doesn’t pay.“ He also called out its use of biometric surveillance to ban employees of law firms suing MSG from attending events at its properties. “I hope that we keep Madison Square Garden on a very short leash. If we renew this special permit as the City Council is considering it, it shouldn’t be by any means in perpetuity; it should be another short time period, because they’ve shown themselves, in my opinion, not to be good corporate citizens.”

As a critic of both MSG’s practices and special treatment for any developer, Hoylman-Sigal finds merit in each of the plans that could replace the GPP but opposes the backroom deals that underlie the process bringing the plans forward to the public. “I believe in public architecture that inspires our city and state,” he said, pointing to the Moynihan station as a good example, despite its failure to increase train capacity.

Alexandros Washburn, Grand Penn Community Alliance executive director and former chief urban designer for the city, aligns with several commentators who view MSGE’s recalcitrance as a bargaining position. The 2013 permit extension expressed City Council’s explicit mandate to find a new site— though MSGE renovated the arena the same year and ignored the demand for a decade. He pointed out that the Yankees and Mets both successfully built new arenas across from the old ones. “For a corporation, [MSGE] will go where the money is,” he suggested. “A new arena is not only a better arena for the fans and the teams, but it is a more profitable arena for the owners.”

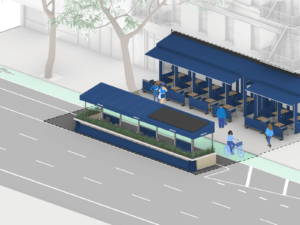

Washburn views ASTM’s plan as only a minor upgrade from the GPP, which struck him as “a bit of sleight-of-hand” in its assumptions about commercial construction (“Towers don’t transform train stations,” he noted; “train stations transform towers” as “a law of urban physics” around infrastructure). He criticized the fact that the plan continues to place the station in the basement of MSG, but finds the notion of international investment a positive sign. His Grand Penn design would clear the MSG site for a new park flanked semi-symmetrically by a New Penn Station to the east and Moynihan Train Hall across Eighth Avenue.

“Madison Square Garden already knows that they have to move and have already indicated that they are willing to,” Cameron said (invoking Executive Vice President Joel Fisher’s hint at a February Community Board 5 meeting that “we would of course listen” to a suitable plan, which they claim not to have seen). He doubts claims that it would be too expensive, citing the $2.3 billion cost of Yankee Stadium and the $1.2 billion cost of Barclays Arena, and estimating their proposed new MSG at $1.5 to $2 billion to build, and suggesting bonds or a public/private partnership similar to the ASTM’s scheme as the means of financing.

The Case for Relocation

“What I never understand in this argument,” said Cameron, “is why James Dolan and the Dolan Company and Cablevision get to rule over the rest of New York: It’s absurd. And [the city] should absolutely take away their tax credit until they’re willing to cooperate.”

He suggests making room for the revival of the original Penn Station by shifting MSG to one of several proposed sites, probably 34th Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues opposite Macy’s, where its footprint fits neatly, combining certain radical moves (e.g., Sixth Avenue passing underneath, creating a large pedestrian area at Herald and Greeley Squares) with new hotel and tower components that would serve the developers’ bottom line. Cameron’s drawings include a new park, across 33rd Street north of the station, that he names after Pennsylvania Railroad president Alexander Cassatt; some also wistfully feature an un-demolished Hotel Pennsylvania.

Around the world, Cameron points out, cities regularly rebuild damaged or aged structures: he cites baroque Dresden after World War II and Japanese Shinto temples recreated on 25-year schedules. New York could perform a comparable recovery, he believes, undoing the fatal error of 1963. Components of Penn are available for reuse, including its foundations remaining below ground, and the MSG structural columns that could be removed. There is also a partial head start toward the adaptive-reuse principle that the greenest building is the one already there: “Most of the stone from the original Penn Station is just lying around out in the Meadowlands,” he said.

All of MSG’s current subway and commuter-rail infrastructure would be close at hand, and quotidian details could be sorted out as well, such as making it easier to bring in service trucks without intersecting with as many pedestrians.

Cameron’s proposed New MSG would also offer its owners prolonged, stupendous financial incentives, and he conjectures that this will prove decisive. Presumably Dolan wants to negotiate for a better deal, he argues, calculating the current tax break’s value at billions of dollars over the course of decades. “Why wouldn’t we just say to them, ‘Okay, you’ve got a $50 million tax credit now; if you agree to move, we’ll give you a $75 million tax credit for the next 30 years’?”

A new Garden site would also go a long way toward rehabilitating the image and legacy of Dolan, a frequent occupant of the local and national media’s pillory. With the facial-recognition-software incidents, Dolan’s reputation has reached cartoon-villain levels. Cameron argues that the public benefits of moving MSG would quickly rehabilitate his public persona.

The Case(s) for Through-Running Service

Improving rail service remains the pressing priority and a point of contention. Turvey of ReThinkNYC sees a best-case scenario integrating an aboveground Penn into the group’s wider Regional Unified Network, the sweeping multimodal, multi-station vision promoted since 2014 by Venturi, though he finds some virtues in ASTM’s plan. It calls for removing the MSG’s Theater, which would admit daylight from Eighth Avenue and reduce local truck traffic, he notes, and the plan as presented to date, silent about Penn South expansion, does not require GPP’s demolition of Block 780, including St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (an 1872 Napoleon LeBrun Gothic building, landmark-eligible and listed as “threatened” by the Historic Districts Council) and the Music Street area of West 30th. “I think [ASTM’s] is a substantial improvement over the present plan,” he said. “I don’t think it narrows the gap nearly enough with the other plans for Penn Station we were talking about, but they are to be given a lot of credit for addressing and solving many of the issues with the present proposal.”

He also speculates that MSGE may reconsider its position about moving: “They’re going to be thinking about building a new arena soon, and by soon I mean in the next five to ten years.”

On the question of Penn South, Turvey separates the advantages of through-running service from the assumption that acceptable service requires additional tracks. “If you build more terminal tracks into Penn Station, you’re building a dated, congested model that doesn’t work,” he said. “You could implement the international and far better standard of through-running without demolishing 31st Street or 30th Street at all.”

Turvey assails the RPA’s reliance on a study by FXCollaborative and engineering firm WSP dismissing through-running as an alternative to southward expansion to relieve congestion at Penn and Moynihan. Calling for unbiased consideration of ReThink’s through-running plan, he also criticized the RPA’s proposal for through-running service that involves demolishing 31st and 30th Street and building a station deep underground that requires two new East River tunnels to function, which might require decades to build.

Conversely, RPA president Tom Wright is convinced that building Penn South is unavoidable, and doesn’t believe the expansion of Penn Station’s service can be handled by reconfiguring the tracks and platforms within the station. “I haven’t yet talked to a single civil engineer and transportation expert who’s looked at it who agrees with them,” he said. Wright speaks cautiously of eminent domain as a mechanism that should be limited to unambiguous public goods, not used for private development. About a 50 percent expansion of Penn’s capacity will be needed, he said, including two new tunnels running east from Penn to Sunnyside Yards to allow for through-running operations. “We currently have four tracks under the East River, and we’re going to need six; everybody knows it.”

Problems Stated Differently

New York’s historically successful major projects like Central Park, Rockefeller Center, and the renovations of Bryant Park and Grand Central transcend a Manichean framework, according to Washburn. “When the public interest is served at its best, private interest always benefits…. I don’t think the argument right now is which one of these projects is the right project. The argument is, we need to do something that is great enough for this city and that serves the public, truly serves the public and the private interests.”

Washburn’s Cooper Union presentation in January included a passage that his mentor Daniel Patrick Moynihan sometimes quoted from French author Georges Bernanos: “The worst, the most corrupting of lies are problems poorly stated.” If the Penn/MSG problem has been framed as a battle pitting the private property against the public realm, there may be preferable ways to construct it. The debate can also be framed as politics-as-the-art-of-the-possible versus a contention that the city, the railroads, the developers, and the Garden have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to right the historic wrong that ignited New York’s preservationist movement. We can create inspiring conditions for commuters and travelers who have endured dreary commutes for over six decades, and give the city facilities worthy of any metropolis on Earth.

Bill Millard is a regular contributor to AN.