Denise Scott Brown In Other Eyes

Edited by Frida Grahn

Birkhäuser

€36

It was 1965. A 34-year-old Denise Scott Brown arrived in Los Angeles amid one of the hottest summers in that city’s history to start a new teaching job at UCLA. Flickering images of Watts, police helicopters, and bigoted city officials each doing their best Dirty Harry impersonation for news reporters were transmitted through television screens into Sears-model living rooms in cul-de-sacs throughout the U.S. The post-war utopia constructed by consumer capitalism, William Levitt, and General Motors was collapsing. It was “a moment when the failures of urban planning were spectacularly on view,” as Sylvia Lavin puts it—a tornado from which a young, Jewish, feminist, architect, planner, activist would emerge, and change history.

Frida Grahn’s Denise Scott Brown In Other Eyes is a bold feat of scholarship that contextualizes Denise Scott Brown’s teaching, writing, design philosophy, and activism with vignettes like the one above in a way that no other book has to date. Grahn’s anthology depicts Scott Brown through the lens of twenty-three scholars, architects, friends, and former students each indebted to her in one way or another. It features texts by Mary McLeod, Sylvia Lavin, Jacques Herzog, James Yellin, Sarah Moses, Carolina Vaccaro, Stanislaus von Moos, and Joan Ockman, among other luminaries. The masterfully curated bildungsroman published in Birkhäuser’s Bauwelt Fundamentes follows a person named Denise Lakofski and shows how she became Denise Scott Brown, tracing her winding journey through rural Zambia, suburban Johannesburg, London, Rome, Venice, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and of course, Las Vegas.

“Learning to See”

Legend has it that a young Edward Hopper got his ideas for paintings while riding the train from the Hudson Valley into Manhattan en route to his newspaper job. His vantage point on a fast moving, elevated train car humming through the streets of a bustling metropolis gave him unique perspectives into the lives of everyday New Yorkers; revealing slice-of-life scenes that he found beautiful and sought to illuminate as such.

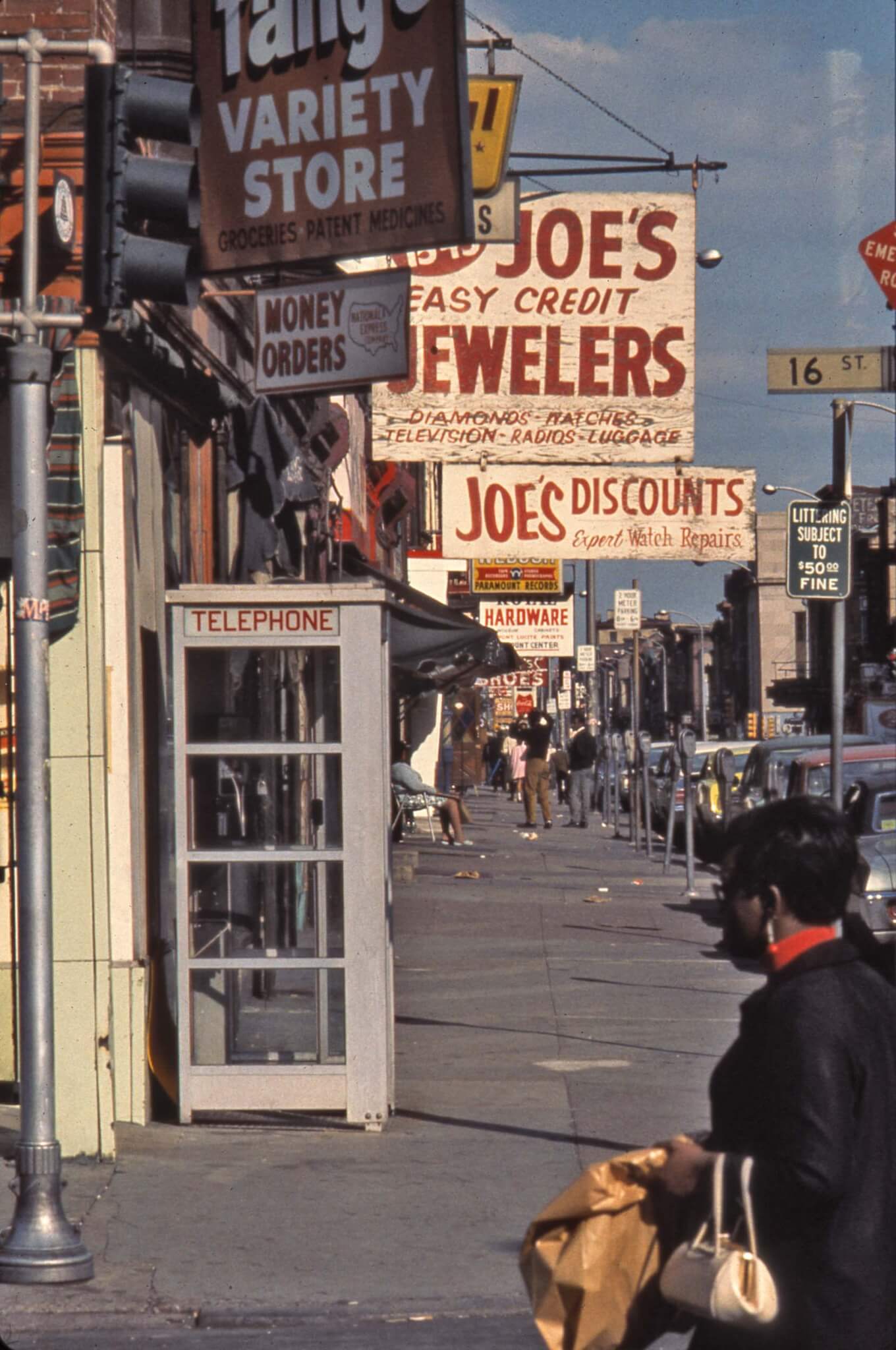

How Hopper saw New York, Denise Scott Brown saw the United States; in all its gritty, contradictory, unforgivably unjust, but sometimes beautiful forms. In Sylvia Lavin’s text, she describes the long train rides Scott Brown took back to the east coast after resigning from UCLA in the late 1960s. She paints a portrait of a young academic, unsure where life would take her next. “As a result, she set off on a journey across the United States,” Lavin said, “spending long hours on the train town-watching, listening to residents of Birmingham tell her ‘what you read in the papers about us was exaggerated,’ to isolated towns in what seemed to her an African desert ‘communicate,’ and to students as they mobilized for free speech at Berkeley.”

Upon Scott Brown’s return to Philadelphia, Sarah Moses notes that “the construction of the Crosstown [Expressway] was liable to displace 6,000 or more individuals, 90 percent of whom were Black.” Set in the backdrop of the “Long, Hot Summer” of 1967, Moses’s contribution describes the fight Scott Brown put up against the Crosstown plan, and how the grassroots activist effort affected her thinking about the city. Moses’s prose reveals how it was on South Street in Philadelphia working hand-in-hand with Black community leaders against racialized infrastructure planning where Scott Brown and Venturi began to consider that Main Street might almost be alright.

“We laugh so we don’t cry”

Scholars like Vincent Scully haven’t done the best job of highlighting Denise Scott Brown’s activism, specifically her work with marginalized groups in Los Angeles and Philadelphia; something by comparison Grahn’s anthology excels in. At best, her advocacy planning was a footnote to descriptions of Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates’ (VSBA) formalist thinking. At worst, Denise Scott Brown’s name was omitted from discussions about VSBA entirely. Scully himself was notorious for doing so. Sylvia Lavin calls attention to this, writing how Scully was “a key force both in maximizing Venturi’s identification as the seminal author of architectural postmodernism and in minimizing Scott Brown’s contribution to their collaboration for decades. Instead of receiving their support, Scott Brown was harassed by many of her male colleagues, particularly during the time she spent in Los Angeles.”

Grahn’s anthology is fraught with such accounts of misogyny that Scott Brown endured. Quoting Jacques Gubler, Grahn describes how at a 1978 CIAM in Switzerland, Scott Brown was “respected as the wife of the speaker” Robert Venturi. Archives from the congress show that Scott Brown’s own name was largely omitted from speaker notes despite the rinsing critique she delivered of the Athens Charter, which arguably changed the course of urban history.

Such instances recall similar episodes that don’t appear in the book but nevertheless are historically significant. At a dinner party, a drunken Colin Rowe once approached Scott Brown and exclaimed “Denise, cara mia! Fuck you bitch.” Immediately after, Collage City’s alcoholic author poured his whiskey down her back, to the amusement of their fellow attendees who supposedly laughed like jackals. Years later in a 2001 interview, the misogynist TV personality Charlie Rose somehow butchered Scott Brown’s adopted Anglo-Saxon name on national television when she was invited to a discussion alongside her husband. After doing so, the camera pans from Rose to Scott Brown, noticeably irritated but smiling through the frustration, trenchant against a scenario which had played out countless times in various forms throughout her career. Clearly, she had been there before.

Due to gaps in scholarship surrounding Scott Brown’s activism and unadulterated male chauvinism in architectural historiography more broadly, there’s a cloud today hovering over her thinking. Was she apolitical? Was she merely a decorator of late capitalism, as her chief detractor Kenneth Frampton lampooned her?

Denise Scott Brown In Other Eyes does a good job of setting the record straight. It reveals a multidimensional woman enmeshed in the New Left politics of her time who cared deeply for the inner city working class, and little for what her critics had to say, or the “armchair academics” and the “radical chic architects who patronized her,” to quote Valéry Didelon, whose own erudite contribution draws a link between Learning from Las Vegas and Susan Sontag’s ruminations on “camp” to show how VSBA’s thinking was in fact deeply political.

Against “a spurious and dull unity”

Apart from impressive readings into Sontag and Learning from Las Vegas, texts by Katherine Smith, Stanislaus von Moos and Christopher Long do much to distance Denise Scott Brown’s and Robert Venturi’s flavor of postmodernism from later iterations (like that of anti-Semite Philip Johnson, for example). In his piece comparing Scott Brown’s thinking to Josef Frank—a Viennese Jewish architect who, like Scott Brown’s family, fled European fascism—Long notes how Frank and Scott Brown held familiar loathing for how postmodernism was appropriated by grifters, saying that both agreed how the late movement was “superficial and lacking in real intellectual underpinnings.” Such analysis should draw a line in the sand for anyone with misconceptions between Scott Brown, Venturi and those who at first detracted their ideas only to later espouse their formal thinking—minus the politics.

To fully render her subject, Grahn’s kaleidoscopic bricolage oscillates between the densely theoretical and the deeply personal. But perhaps Grahn’s greatest achievement is showing how truly heroic Scott Brown is, while resisting the tendency to lionize her. This is achieved by inviting a wide spectrum of commentators, as opposed to a single interlocutor, to tell Scott Brown’s story; a genre defying experiment. The result is a cacophony of voices that each provide their own unique perspective and flavor about an individual they admire greatly, and a story of perseverance against a system not made for you.