The Philadelphia School and the Future of Architecture

John Lobell | Routledge | $136

New York City is a capital of architecture and of public relations; when it builds almost anything, you’re sure to hear of it. But 80 miles south is a city less given to self-promotion: Philadelphia is full of great things that you may well just not hear about. A prime example is the story of The Philadelphia School, an architectural belle epoque spanning the 1950s and 60s. The term first appeared in the April 1961 issue of Progressive Architecture, but not unsurprisingly it hasn’t been explored very deeply. We know about Kahn and Venturi and Scott Brown, but then Philly attention tends to drop off dramatically. Luckily though, this gap has been rectified by John Lobell’s new book, The Philadelphia School and the Future of Architecture.

Encapsulating any artistic school is intrinsically difficult, yet Lobell deftly taxonomizes here. There were clear tendencies that spanned the personalities involved and “threads,” as he put it, that connected even disparate work. He takes a non-chronological approach, focusing roughly on the forest of the larger setting (Penn’s Woods, if you will), then architects and instructors, and finally, the “trees” of individual projects.

He knows a thing or two about all of this, having attended the University of Pennsylvania in these prime years from 1959 to 1966. The Philadelphia School was an artistic movement, but in a real sense the Philadelphia School was also the University of Pennsylvania Architecture program.

“It was a “golden age” when students chose between Robert Geddes, Romaldo Giurgola, George Qualls, and Robert Venturi for their studio critics (the choice varied a bit from year to year and each taught with a colleague); Kahn and Venturi were transforming architecture; Robert Le Ricolais was building experimental structures; Karl Linn was applying Zen Buddhism to architecture and pioneering vest pocket parks; Paul Davidoff was raising the issue of poverty and developing advocacy planning; David Crane was working on the capital web; Ian McHarg was questioning progress in Western civilization and advancing urban and regional ecology; Herbert Gans was moving into Levittown; Denise Scott Brown was forging a syncretism of European and American planning and discovering popular culture; and Edmund Bacon was directing the most active planning commission in the country.”

And that isn’t even all, with additional instruction from Sasha Nowicki, August Komendant, and many more.

How did this happen? Largely due to the talent-spotting of G. Holmes Perkins, appointed dean in 1951. Reviving the school from a relatively slack period after the earlier Paul Phillipe Cret deanship, Perkins skillfully filched some established faculty from elsewhere but mainly focused on emerging talent.

What did they do? And what did they think?

The school advanced a modernism that was more balanced than prior strains, with revolutionary zeal tempered into a more practical Girondism. It was more open to a variety of humanist and historical concerns, Lobell asserts. “You cannot copy the past if you do not know it, but neither can you learn from it; the Philadelphia School rebuilt an approach to the past.” Giurgola’s instruction on the development of architectural theory valued both the past and concerns well beyond the technical, with readings stretching to include Hegel and Merleau-Ponty. Venturi’s classes were, of course, all over the map, and Kahn Master’s classes were full of gnostic pronouncements, but the expectation was very real buildings.

All of this produced the reverse of paper architecture. Its ethos was consistently practical; when Venturi and Scott Brown are your zaniest members your provocations will remain reliably realizable in the real world. Much of the faculty had practices in the city. Lobell wrote, “at Penn, pressure was always on for architectural ideas to be buildable in the here and now.”

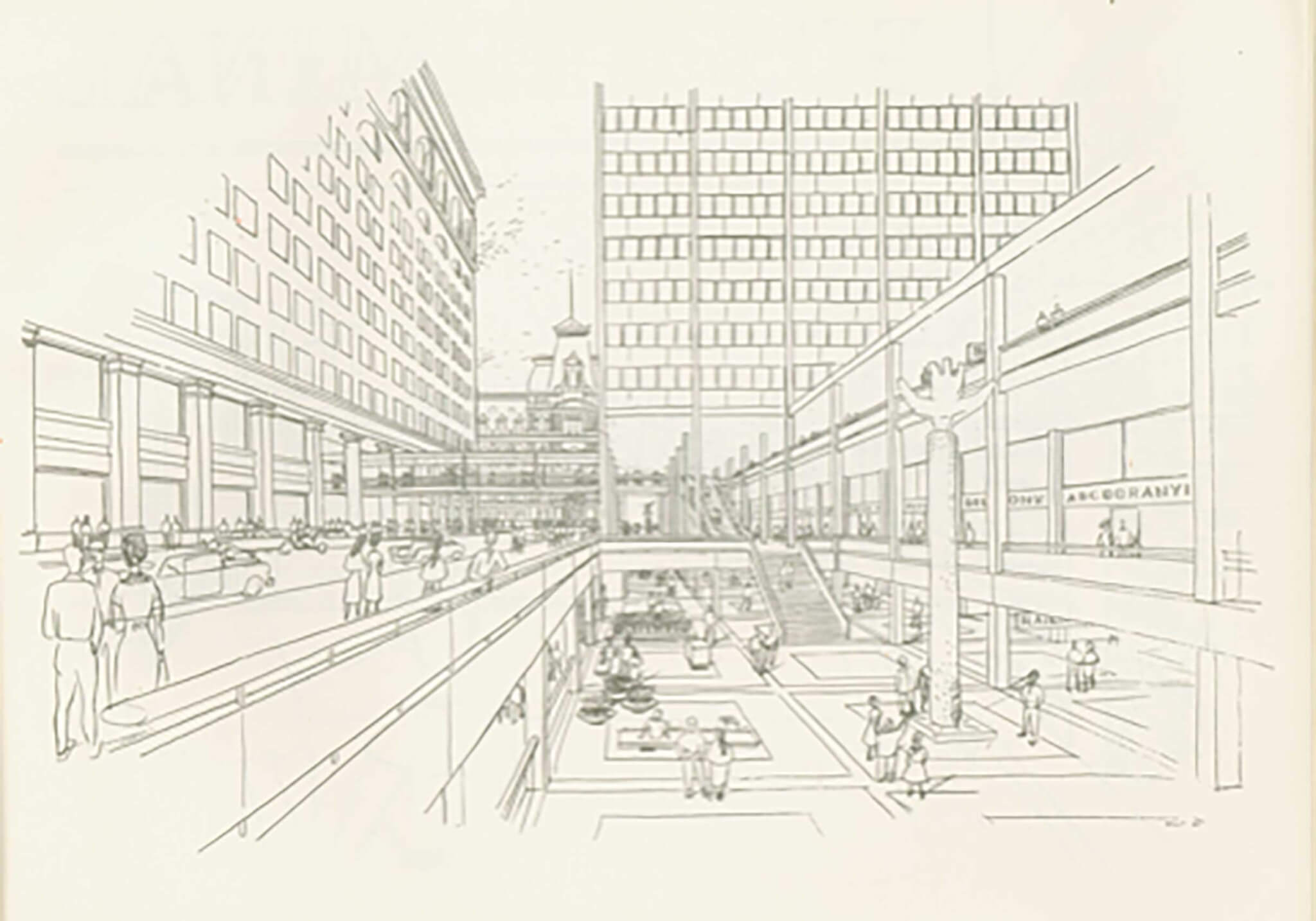

Urban context was also a prime consideration “At Penn, we were admiring of Rudolph’s Yale Art and Architecture building and Saarinen’s TWA Terminal, but our architecture was different, an architecture of buildings meant to be experienced not through a 35mm perspective correcting lens, but as part of a street, a neighborhood, a city.” This wasn’t merely an aesthetic stance, there was a new level of attention to the city as an organism, to social concerns, and to nature, which preceded a number of other schools coming back around to these things.

None of this, however, entailed a turn from one of the core tenets of modernism—a high level of structural expressiveness, and a belief that a building’s aesthetic should derive from an honest expression of its spaces, its structure, and its materials. Open plans were relatively rare, and designs usually prioritized plan over section. They liked diagonals, deviations from rectilinearity were frequent. Masonry and concrete unquestionably supplanted steel and glass. Or more succinctly, as Lobell puts it, “there was a lot of Corbu, a little Wright, and almost no Mies.”

Lobell singles out a number of structures for closer inspection. Some of them are familiar, like the Trenton Bath House, the Guild House, and the Vanna Venturi House. However Lobell doesn’t write more than he needs to. On Giurgola’s Walnut 32 Parking Garage: “Function, mechanical, structure—nothing more. The function is expressed in the ramping floors taking one winding up looking for a space.” Other structures he highlights are less well-known though, adding to the emerging understanding of the School: Giurgola’s excellent Boston City Hall Proposal is examined, diagonal-laden, and useful, with a near-continuous counter running along exterior glass. We also see Geddes’ demolished Pender Laboratories at Penn and dormitories at the University of Delaware.

So, what happened? The team splintered, like many successful sporting rosters, not due to failure but due to success, with talent scattering across the country in the late 60s. The legacy faded for most of these conscientious practitioners as showboats elsewhere hogged the spotlight, as usual. Lobell notes the rise of the New York Five, (the Whites) versus the Philadelphia School’s Grays. In simplified terms, the Whites and the Grays form a perfect opposition—architecture as a formal game of language versus architecture as engaged with life; architecture meant to be viewed as drawings or isolated buildings, versus architecture as a part of its surroundings. These caprices attracted attention, but many of the core concerns of the Philadelphia School—architecture that is more mindful and respectful of history, context, social issues and ecology—spread steadily, in such a way as to obscure this important early germination.

Lobell’s account offers particular force because it’s not just an examination, but an argument for the importance of this particular moment and for the measured range of concerns they skillfully balanced in producing this work. This sort of humanism deserves a revival. He writes: “So yes, Kahn’s buildings are rich in form, as are those of Giurgola, and as Venturi Scott Brown’s are rich in signs, but in all cases, those forms and signs are pointed to our lived experiences. In Giurgola’s words, ‘People are born in, live their lives in, and die in our buildings.’ How should we experience our lives today? We await our architects.”

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn. His work has been published frequently in The Wall Street Journal, Metropolis, Citylab, Architectural Record, The Guardian, The Financial Times, and others.