Sculpture: The Work of Hans Noë

Curated by Lawrence Weschler

Composite Gallery, National Museum of Mathematics

11 East 26th Street

New York

Through October 31

As starchitecture increasingly becomes faux pas with the public’s disillusionment of individuals (Meier, Johnson, Adjaye, et al) once considered design demigods, Hans Noë—a 95-year-old Holocaust survivor, sculptor, architect, and recluse residing in Hudson Valley, New York—may be understood as an anti-starchitect. His remarkable talent, life story, and chagrin for the public eye renders the Jewish artist/architect refreshing amid the current culture saturated by personality cults.

After escaping European fascism and a stint in New York City, Noë has spent the last five decades working out of his self-built home in Garrison, New York. There, he’s produced an enormous amount of geometric wooden maquettes imbued with subtle poetic meaning—all in relative isolation and without celebration.

This September, a retrospective curated by author Lawrence Weschler showcasing Noë’s truly impressive, never-before-seen art corpus opened at the National Museum of Mathematics located on the northern end of Madison Square Park in Manhattan.

Through October 31, Sculpture: The Work of Hans Noë is on display at the children’s museum which showcases artworks made by Noë not far from the 1960s downtown Manhattan art scene he once commanded before fleeing the limelight.

The “Hiding Master”

Hans Noë was born in 1928 in Czernowitz, a city in the Bukovinian region on the edge of the Austro-Hungarian empire where 250,000 people lived—140,000 of which were Jews—in what is now southwestern Ukraine. As a young boy, Noë’s life changed forever when he saw the magisterial central synagogue just down the street from his family’s home get torched by the fascist Romanian army. Between the ages of 13 and 18, Noë was in hiding from the gestapo, going back and forth between the Romanian forest and remote villages. “He spent most of his teen years crouching in the fetal position, terrified of showing his face,” Weschler told AN.

Despite the mass-killing of Czernowitz’s Jews (almost 100,000 were executed), Noë and his family miraculously survived fascist occupation. His family moved to New York City in December 1949. In 1950, age 21, Noë enrolled at the then-free Cooper Union, studied architecture, and became a protégé of Tony Smith, and later Mies van der Rohe and Ludwig Hilberseimer at Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT). After a short stint in Chicago, Noë cut his teeth in New York’s downtown art scene, having been introduced by Smith to Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Ad Reinhardt, Theodoros Stamos, and others.

Escaping the “Whole Delusional Rat Race”

Between 1963 and 1971, Noë designed and built a dozen modern homes, often by himself. Despite his uncanny design sensibilities, as someone relatively new to the inner workings of American capitalism, Noë became partially disillusioned with architecture after having to dabble in its business side. “I came to realize how a successful architect has to be not one but three things: he has to be a great architect, he has to be a great self-promoter, and he has to be a great businessman. And I was only one of those three,” Noë told Weschler in conversation.

Noë’s architecture is minimal, site sensitive, comfortable, and cost friendly. In an oral history Weschler compiled about Noë, he notes that his home in Garrison, New York is strategically situated in parallel with a nearby river so as to provide natural heating and cooling; it doesn’t have an air conditioner because it doesn’t need one. In describing his architectural philosophy, Noë told Weschler his work is “handmade to the extent possible, cheap,” and “the simplest possible solution to the problem posed.”

It was also during this period when Noë bought an abandoned building on the corner of Mercer and Prince Street in SoHo, and converted the upper floors into artists lofts and the ground level into a veritable establishment Dimes Square regulars may recognize: Fanelli’s. After entering the restaurant industry, Noë and his wife, Judy—whom he met as a student at IIT—moved upstate to Garrison, New York in the 1970s where the two have since resided, raising their sons Alva and Sasha.

A commonality for Jews in those post war years, Noë was/is brimming with talent, and easily could have become one of the 20th century’s most recognizable figures; but was petrified of entering the public spectacle after witnessing his childhood synagogue burn, and European civil society turn on him amid the rising tides of anti-Semitism and fascism. “I used to imagine my general distaste for self-promotion and my indifference toward fame as sort of emblematic of a certain kind of moral or at any rate aesthetic superiority,” Noë told Weschler in conversation. “With high considered self-regard, I was refusing to enter into that whole delusional rat race.”

“But I’m no longer so sure,” Noë continued. “I think rather that my problem may simply have been one of fear, a prolonged PTSD, as it were, with its roots wending back to my experience of the war, when survival enforced an entire regime of perpetual hiding, since any and every calling of attention to oneself could so easily have proven fatal not only to myself but to my entire family. And maybe it’s just that I never got over that way of being in the world.”

Revisiting Noë

Today, Noë’s son, Sasha, still runs Fanelli’s and Alva is a world-renowned philosophy professor at U.C. Berkeley. For years, Alva tried convincing his dear friend and veteran reporter for The New Yorker, Lawrence Weschler, to visit his father’s studio in Garrison. Upon doing so, Mr. Weschler discovered what he calls a “hiding master” and knew there was a story he had to tell, leading first to a 2021 exhibition at The Fireplace Project in East Hampton, New York, Hans Noë—Architecture and Sculpture, and then to the current show on display in Manhattan.

Despite the exhibition’s location and scientific rigor, Hans himself will tell you he isn’t at all interested in mathematics. Rather, the maquettes on display at the National Museum of Mathematics show Noë’s experiments in form, scale, and color.

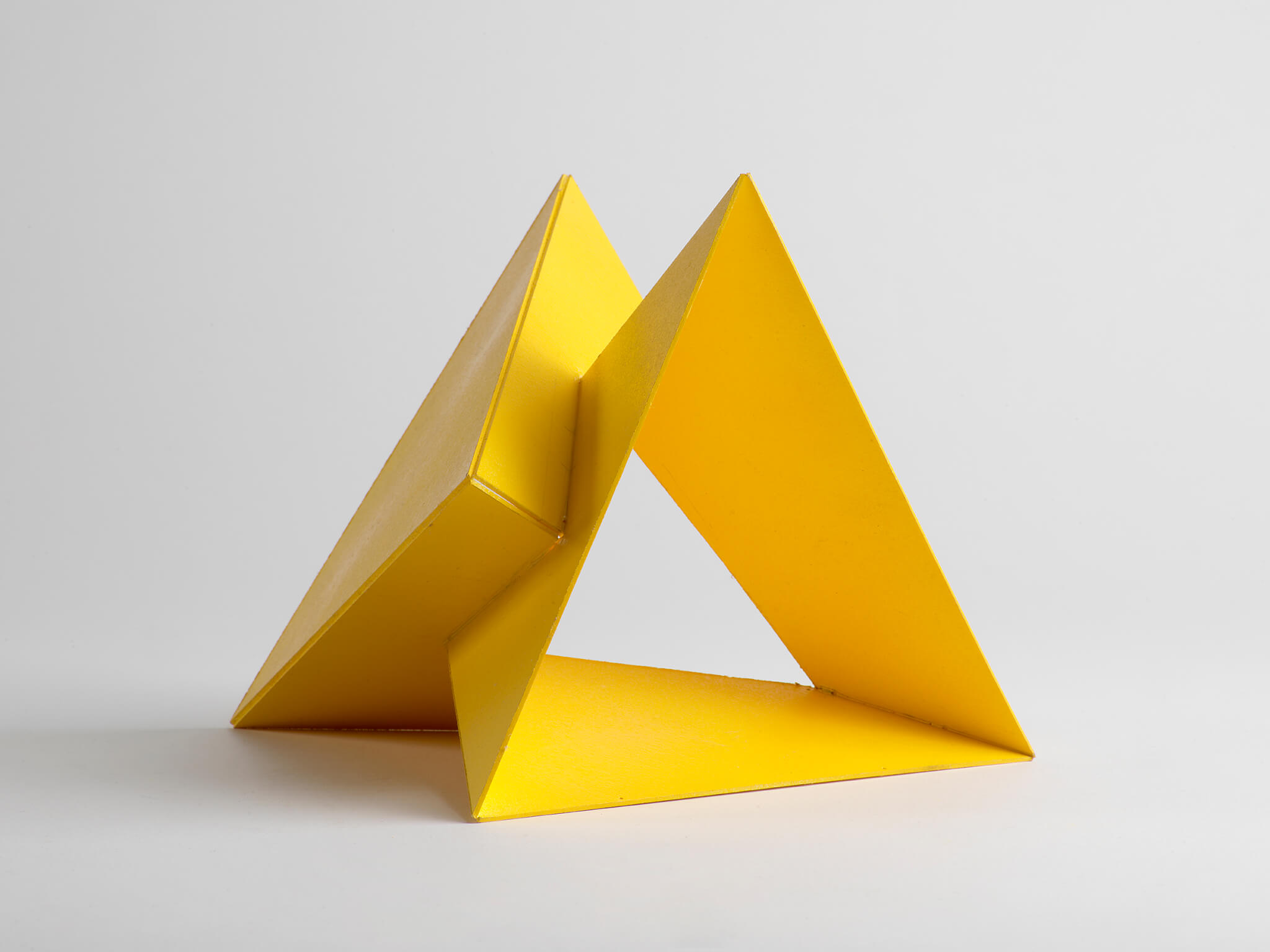

Take for instance a yellow tetrahedron Noë considered submitting as a proposal for the World Trade Center’s reconstruction that is jarringly similar to David Child’s built proposal for the Freedom Tower, albeit more colorful and slightly skewed in its vertical axis. “Daniel Libeskind had never heard of Hans as far as I’m aware, and vice versa,” Weschler said. “Hans wouldn’t be interested in such things anyways.”

The retrospective’s signature piece is a zig-zagging wooden pillar reminiscent of Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column. Upon perusing the show, a flurry of other art history references come to mind: Suprematist models by other avant-garde artists/architects like Vasyl Yermilov or Kazimir Malevych are easy formalist comparisons.

At times throughout my guided tour, there were wonderful discrepancies between the way in which Noë described particular art pieces he made versus how Weschler saw them. Meandering throughout the gallery on a rainy afternoon, Lawrence, with a splendid enthusiasm, requested that I walk circumferentially around each of Noë’s models to experience them in a 360-degree fashion, Renaissance-style.

Several models, from a distance, appear to be mere experiments in form making. But upon closer inspection, and with Lawrence’s guidance, geometric symbols appear such as the Star of David, hidden in plain sight. “Hans wouldn’t tell you that was his intention,” Weschler said. “But that’s what I see when I look at it.”

Noë’s art arguably mimics how he lives. At face value, his models appear as formalist experiments that don’t immediately reveal their true intentions, nor their genius. Following a closer inspection, and with some help from a seasoned curator, they reveal themselves and their deeper poetic meaning. It’s the sign of a true master without the pretenses we in architecture have become so accustomed to—one that’s been hiding, until now.

To hear from the artist himself, join Hans, Lawrence, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, Alva Noë, and others for a round table discussion at the National Museum of Mathematics on October 17 at 6:00 p.m. To register, follow this link.