US Embassies of the Cold War: The Architecture of Democracy, Diplomacy and Defense | David B. Peterson | Onera Publishing | $75

On August 19, the State Department announced the groundbreaking of a new U.S. Embassy in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. With SHoP leading the project as design architect, the building will expand on the Department’s Capital Security Construction Program, which it boasts has overseen the completion of over 177 diplomatic facilities since 1999. Through the Bureau of Overseas Building Operations (OBO), the State Department has been expanding America’s architectural footprint abroad, though with little domestic attention. This lack of stateside attention to the State Department’s architectural activities is the subject of recently published US Embassies of the Cold War: The Architecture of Democracy, Diplomacy and Defense by David B. Peterson.

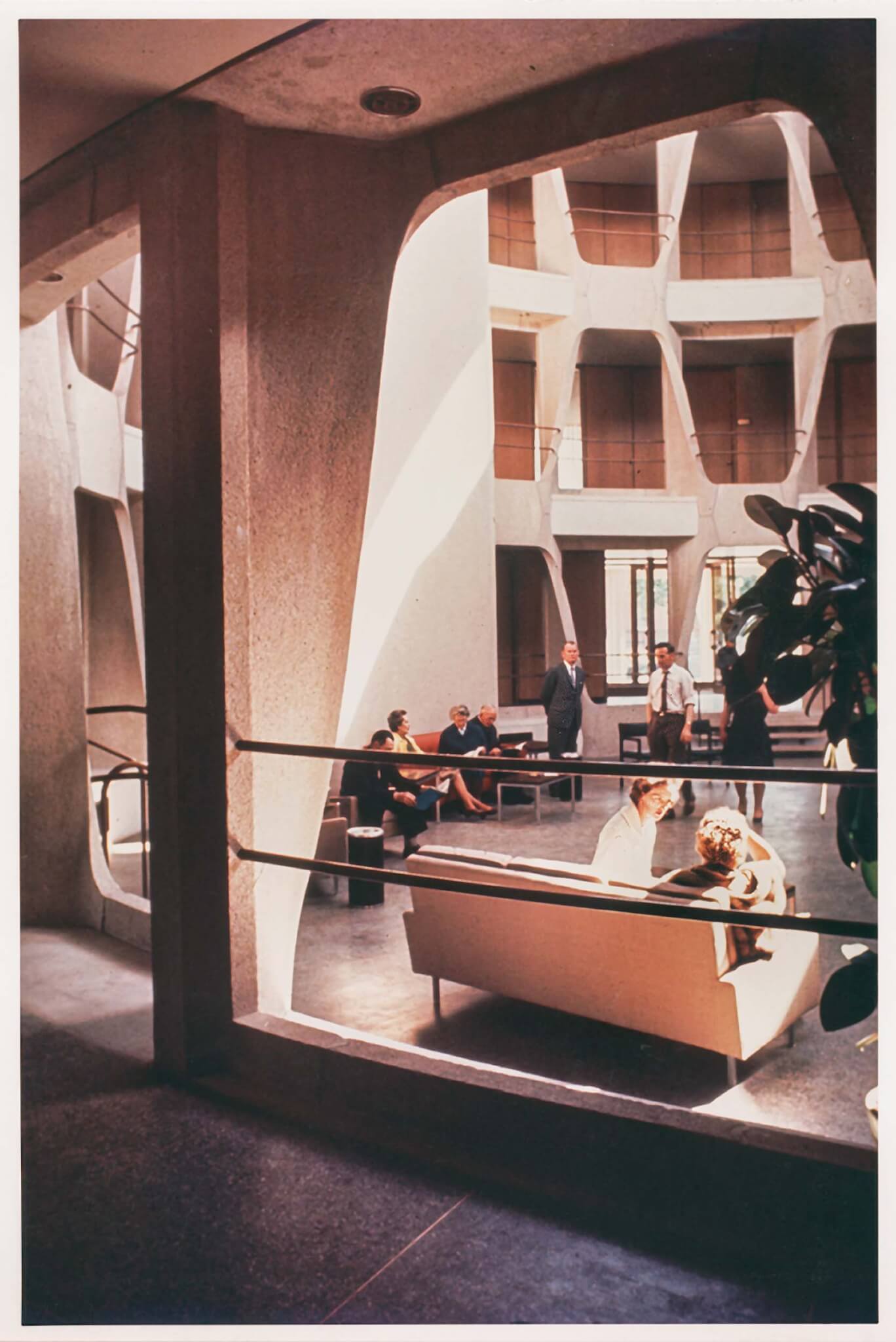

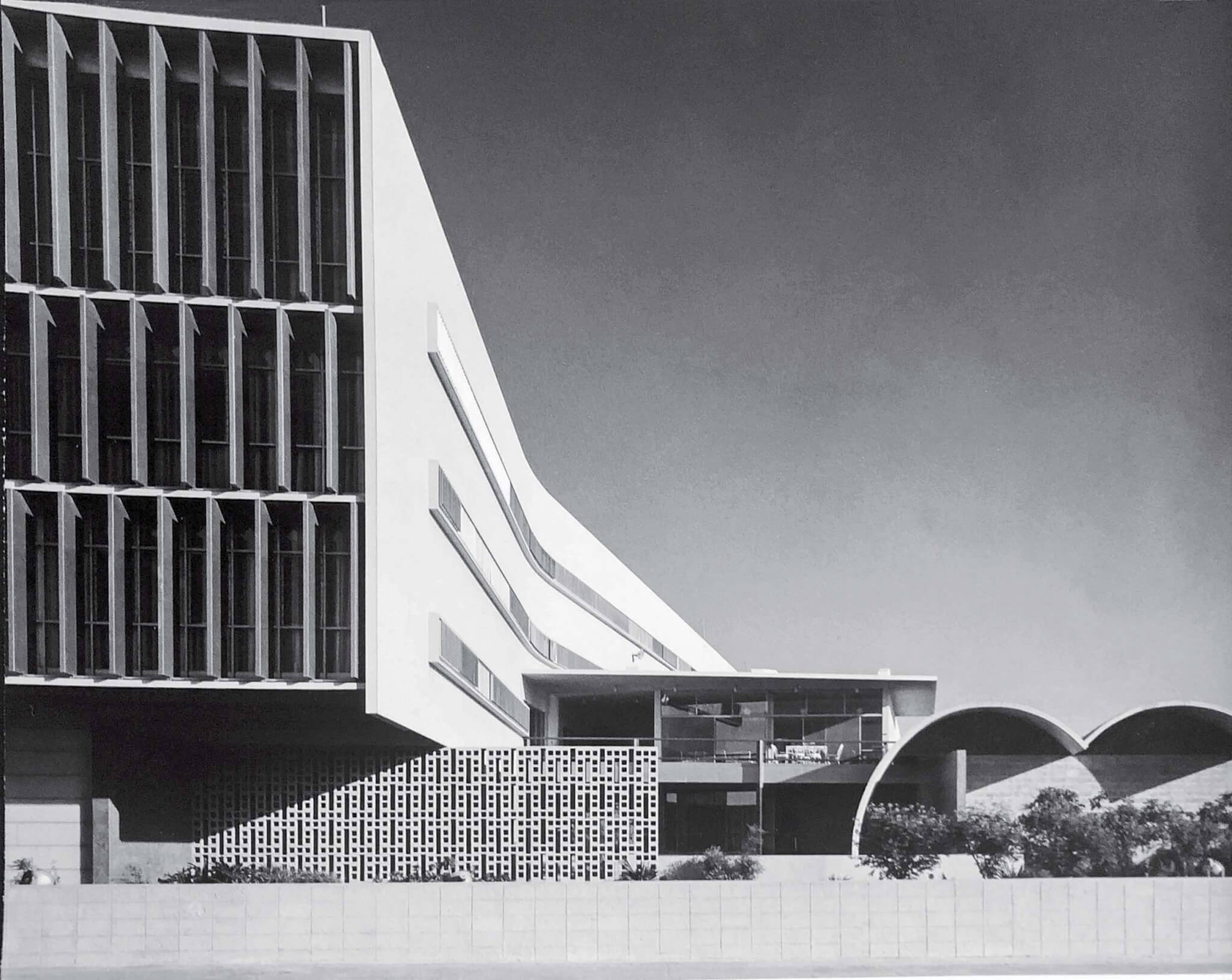

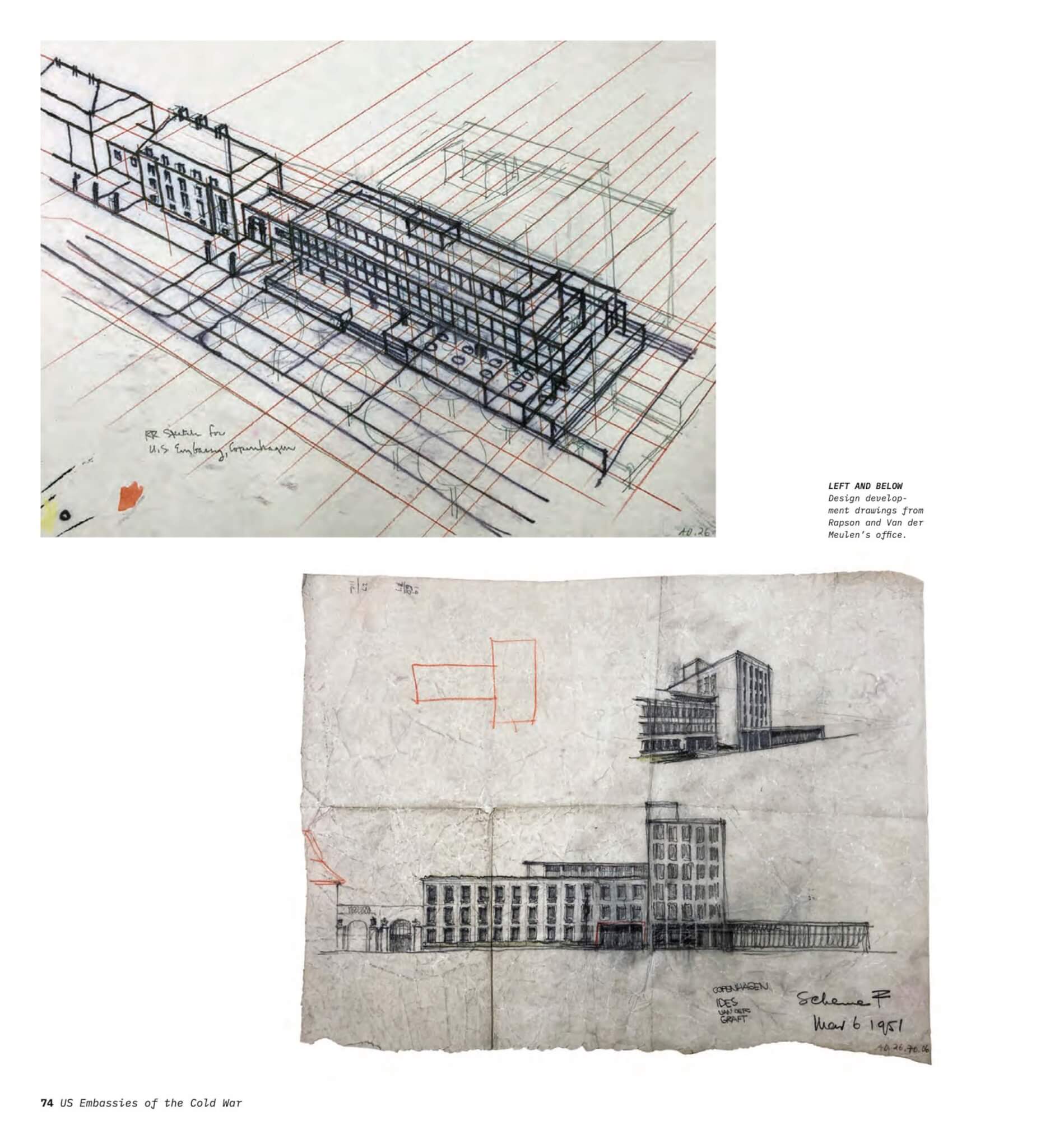

After a speed-run introduction to Cold War history, Peterson devotes most of the book to documenting 14 U.S. embassies constructed under the Office of Foreign Buildings Operations between 1948 and 1957: Rio de Janeiro, Copenhagen, New Delhi, and London, among others. This was a brief era in which the State Department devoted significant funds to commission embassies, hiring a suite of canonical talents including Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, Eero Saarinen, and Josep Lluís Sert to represent America through design. Peterson argued that the work, and history of the OBO, remains underappreciated; his new book therefore documents “the architecture of diplomacy and democracy embodied in some of the most important buildings built by some of the country’s greatest architects.”

The design trajectory across the program is interesting in and of itself. The transition from Harrison & Abramovitz’s International Style design in Rio de Janeiro, which characterizes the earlier approved schemes, shifts to adaptations of vernacular influences meshed with modernist styles in Baghdad (Sert) and Accra (Harry Weese), and to material experimentation with structural concrete facades in London (Saarinen) and Dublin (John Johansen). It’s easy to get lost in the book’s photographs, which elicit the “newness” of the modern style through applications of Knoll furniture and clean concrete. But all these projects included libraries, theaters, and other performance spaces through which to blast American cultural production to local audiences (a photo of the reading room in the London embassy shows The Nation and the National Review displayed next to each other).

Key to Peterson’s argument is that many of these embassies differ from their 21st-century counterparts in that they were meant to project these cultural projects through centrally located, porous buildings. The architecture was envisioned as a representation of America’s welcoming attitude. Today, most embassy buildings are located far afield from city centers and have immense security demands that are often not gracefully incorporated into their larger designs. Peterson also takes note to document the current status of each building, centralizing preservation to the larger project of the book. The question of contemporary reception can be read against Peterson’s research on how these projects were received in their time, looking to reviews from publications including Architectural Forum, Architectural Record, and Progressive Architecture.

What could have been expanded on further—and is important considering Peterson’s framing of these projects as projecting democracy during the Cold War—is a larger synthesis on the goals of these projects, local responses, and alternative receptions of the U.S. abroad. While Peterson points to some local reviews of projects, including from The Irish Times, for example, the association between glass curtain walls and the image of America as furthering global democracy is taken more as a given than it should be, considering the extent to which the State Department simultaneously toppled democratically elected governments it deemed unfavorable. To Peterson’s credit, he cites the Central Intelligence Agency’s use of the embassy in London as a host for the 1962 Vanguard American Painting exhibition as a political act to push a positive American image a few months before the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Politically driven architectural work may be one consistency between the era of design that Peterson has documented for larger appreciation and the OBO’s more recent activities (including WEISS/MANFREDI’s ongoing renovation of Edward Durrell Stone’s U.S. Embassy in New Delhi). While KieranTimberlake’s embassy design in London was the source of much critique, more recent (and less influential) projects from Miller Hull in Guatemala City and Ennead in Ankara may seem less innocuous—and Krueck Sexton Partners’ work on the relocated U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem certainly is not.

Curious AN readers can find a list of firms currently working with the OBO here, and more detailed information on State Department contracts for architectural services here.

Chris Walton is a Master of Architecture candidate at Harvard GSD and a former assistant editor at AN.