Herzog & de Meuron at The Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts

Burlington House, Piccadilly

London

Herzog & de Meuron at London’s Royal Academy transports gallerygoers into a literal Wunderkammer. The curation encourages viewers to engage with Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron’s iterative, exploratory process of testing ideas, but the density of objects and attempts to present the most minute details of the oeuvre make the show a challenge to take in. Jacques Herzog once likened the practice of architecture to ecology: “Whatsoever you do, do it with care.” As in its buildings, Herzog & de Meuron shows that “care” manifests as a desire for total control of the details and an obsession with process.

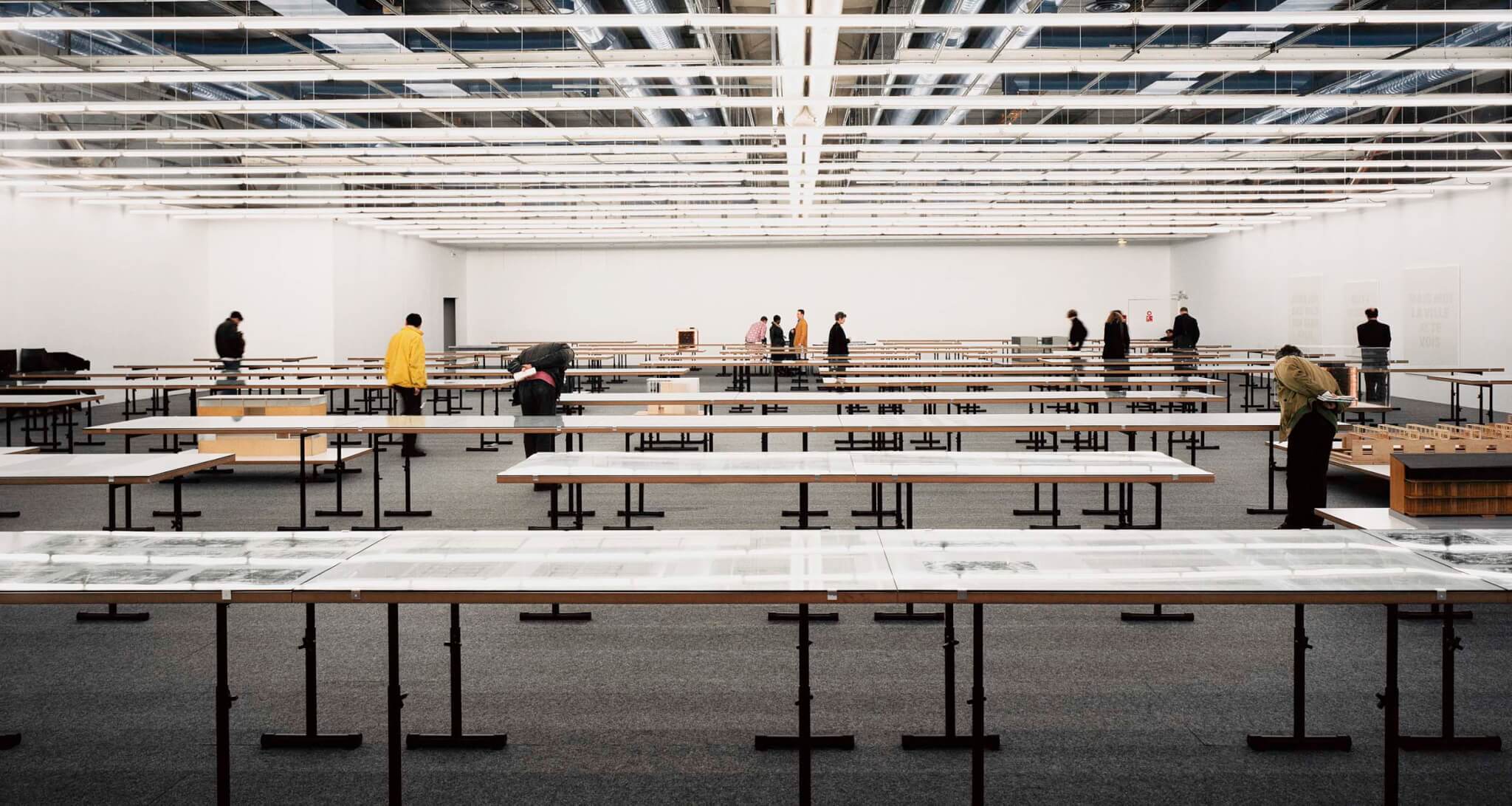

Under the leadership of Esther Zumsteg, H&dM’s curator-at-large, the meticulous archive tells the story of this attention to care. Physical artifacts on show are anchored within a set of three vitrines identical to those at H&dM’s Kabinett archive in Basel; models, maquettes, and sketches all arranged in a loosely chronological order. In addition to directly looking at the objects on display, visitors can point, scan, and explore large-scale facade mock-ups, sectional models, and even “inhabitable” 3D spaces via a bespoke mobile app that offers an interactive AR experience. Snooping around, viewers will find that the model of REHAB Basel gets an AR treatment, with the visual showing the formal diagram of the therapy pool, one of the key nodes within the building’s plan.

Apparently, AR functionality is intended to push the understanding of the relationship between the body and architecture, but the tech does not match the aspiration. Generally, the models have greater clarity without the AR enhancements. There is no scope for a close-up inspection of the CaixaForum models or the massive yet transparent M+ model. Both could have been given a stand-alone vitrine within the show.

There are also several films within the show that offer glimpses into construction sites and factory testing. We see, for example, the deft labors of construction workers setting copper panels in place. Two additional films at the center of the exhibit are also supposed to exemplify the practice’s care for its work, though they reveal this “care” more in terms of attention, or control over, the way the buildings are used after the architects’ involvement has ended. On one side of a divider, three frames play out the day-to-day existence of a series of H&dM projects. On the other, a 37-minute film provides an emotionally rich account of the lives of a group of people who use REHAB Basel as part of their injury recovery. The reflective film links buildings and scenes thematically, with crowds of pedestrians seeming to amble between the forecourt of Fünf Höfe and M+.

If there is an intent to comment on form in Rehab from Rehab, the longer film by Bêka & Lemoine, then it is subtle. The focus here is exclusively on the recipients of care and those who care for them. Gallery attendees hear from Abdel Rehman, a young man affected by the sudden onset of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Extended frames show him performing his daily regimen of strengthening exercises and ambulation around one of the courtyards—a space filled with light and suffused with the color of adjacent greenery.

Later viewers see another patient undergoing an “animal-assisted” therapy program: We watch how, walking alongside and training a dog, he extends his range of motion and muscular strength with each step. Here again, the building takes a secondary role, but it is an important one. The quiet strain of timber underfoot becomes a reassuring accompaniment to the patient’s movement, reminding viewers of the responsive “naturalness” of the material. The timber cladding, with its pronounced grain, also asserts this building’s connection to nature, bathed in sunlight and the dappled shadows of swaying plants.

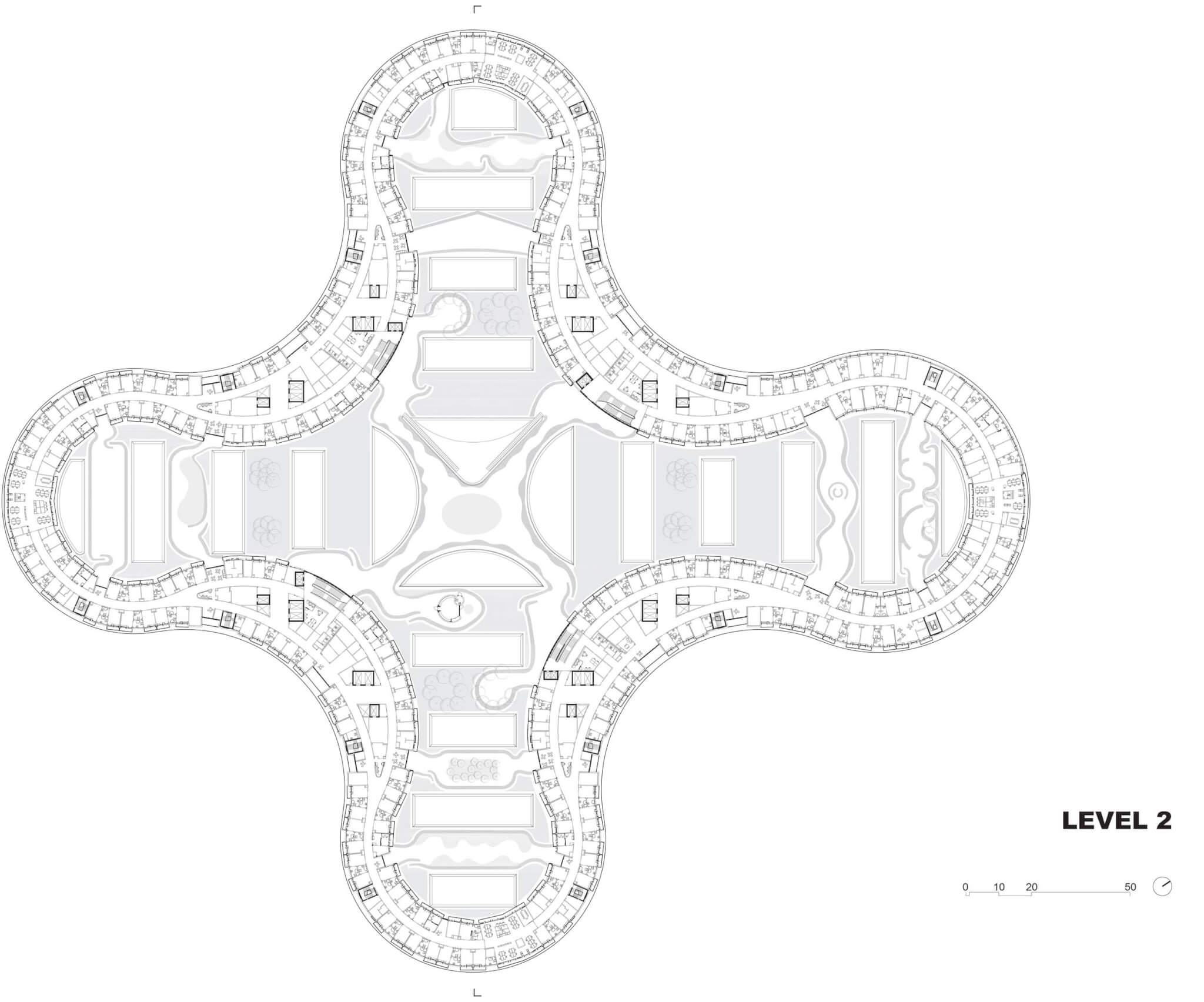

Having reached the climax of the film in the pool of REHAB Basel, the same pool that was animated by diagrammatic pinpricks of light in the vitrine, viewers proceed to a room dedicated to Kinderspital Zurich. Around the room exhibition labels describe the concept: individual recovery rooms, each with a strong domestic feel, collectively arranged as 35 different neighborhoods. The digital presentations here are hit and miss, but at the center of the space is a full-size mock-up of one of the children’s rooms, which again can be enhanced by the app for the “full” AR experience. Panning left and right, the film allows fellow gallerygoers to become part of a rendered scene, complete with timber soffit, a deep window reveal for sitting and watching the world, and visual cues to nature in the form of a sunken planter with verdant foliage.

This latter space suffers precisely because of H&dM’s desire to meticulously present every nuance of this project. As a result, details get lost in the thick of things. One exhibition label reads: “Highly specific joining of concrete and wood elements are an integral part of the identity of the new hospital.” The drawings presented beside this text are printed at a size and resolution that requires a determined effort to decipher.

Though the coherence of the content falters in this final room, the overall message is clear: Here is a practice not only interested in working on towering apartment buildings and high-profile galleries, but one that is also resolutely interested in the architecture of holistic care. Many exhibition viewers choose not to end in this final room but to return for a final viewing of Rehab from Rehab. One of the doctors in the documentary comments: “This is a therapy-free space. … People are just enjoying what they do.” This is what Herzog & de Meuron’s intense consideration and exhaustive testing achieves for recuperative facilities and, in fact, all typologies: Functionality becomes a given, to the point where users can enjoy the finer qualities of the everyday.

Josh Fenton is an architectural writer and communications consultant based in London.