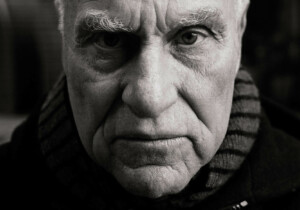

Eugene Edwards Aubry died on December 9, 2023. He was 88. A musician, storyteller, and fluent sketcher, Aubry was also a prolific architect. During the first half of his career, he practiced in Houston; during the second half, in Sarasota, Florida; and Northeast Harbor, Maine.

Aubry was born in Galveston, Texas, in 1935. As a teenager in the early 1950s, Aubry was a member of his high school blues band. He was accepted at what is now the University of North Texas in Denton, Texas, where he hoped to study music. His father, who worked for the U.S. Engineer’s office in Galveston, thought this was an exceedingly poor career choice, causing Aubry to switch disciplines—and universities—to study architecture at the University of Houston instead.

Aubry’s skill as a draftsman and designer, as well as his self-confidence, attracted the attention of the architecture school’s foremost design critic, Howard Barnstone. In 1958, one year before Aubry’s graduation, Barnstone hired Aubry to work part-time—and subsequently full-time—for his firm, Bolton & Barnstone. In an interview published in Making Houston Modern: The Life and Architecture of Howard Barnstone, which I coedited, Aubry recalled how he learned to intuit the direction Barnstone wanted to pursue, as well as how not to “push his buttons:” Dealing with the mercurial, charismatic, bipolar Barnstone required constant attention to mood and affect.

Accommodating Barnstone’s unpredictability earned the young practitioner a name on the door: In 1966, Barnstone reorganized the practice as Barnstone & Aubry. Aubry was not only a designer: He was also responsible for overseeing production of construction documents, coordinating with consultants, administering construction, and dealing with clients’ anxieties and complaints, for which Barnstone had no patience. But Aubry was also given access to the world of Barnstone’s clients—notably the Parisian immigrants and art collectors, Dominique Schlumberger and John de Menil—as well as the world of contemporary architecture.

After Aubry left the firm in 1969, he finalized design on three of the partnership’s most important buildings: the Rothko Chapel (1971) and the Rice Museum and Media Center (1969 and 1970, respectively), all commissions received from John de Menil. Philip Johnson was the original architect of the Rothko Chapel but resigned the commission because Mark Rothko objected so strenuously to Johnson’s design of the skylight. It was Aubry who worked out the skylight design to Rothko’s satisfaction, obtained the artist’s concurrence on such details as the interior floor surface, and surreptitiously consulted with Johnson to organize the chapel’s site plan.

Aubry said that in spring 1970, just months after leaving Barnstone, John de Menil advised him to accept an offer made by another Houston architect, S. I. Morris, Jr., to join Morris’s practice, which in 1972 became S. I. Morris Associates. Morris and Aubry repositioned the firm to pursue prime commercial and institutional jobs that Houston clients were increasingly awarding to well-known, out-of-state architects like Johnson. In 1980, the firm became Morris Aubry Architects.

The decade between 1972 and 1982 marked not only one of Houston’s peak economic cycles but an architectural high point as well. Morris and Aubry demonstrated that Houston architects could hold their own against out-of-state competition in terms of design. The office did just that, often for developer Gerald D. Hines, who made design distinction essential to his building projects.

Aubry’s design work with Morris cohered with the architectural movement that critic Charles Jencks labeled “Late Modern.” Aubry’s restless energy, impatient temperament, and flair for improvisation were apparent in the diagonally inflected planes and sleek surfaces of many of his designs of the 1970s, as well as in his embrace of pop art icons and references: Aubry extrapolated the octagonal floor plan of the Rothko Chapel for Stephen P. Farish Hall (1971), and the Houston Public Library’s Central Library (1975). Pop art visual puns were embedded in the design of the Glassell School of Art of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH, 1978), with its signature glass-block curtain wall, and the Brown & Root Southwest Houston Office Building (1980), which was a bow-tie shape in plan. Aubry jokingly referred to the 49-story First City Tower (1981) in downtown Houston, with its stair-stepped exterior notches, as his “nacho building.”

Four of Aubry’s smallest buildings generated the only architectural movement—the Tin House movement—to emerge from Houston. Aubry recalled that at dinner with Dominique and John de Menil in December 1968, John de Menil confided that they were facing a crisis. The Menils had just announced that they would sever their ten-year partnership with the University of St. Thomas and transfer the Institute for the Arts to Rice University. The Institute was contractually obligated to present an exhibition from the Museum of Modern Art at the end of March 1969, but now there was no place for it to be shown. Menil asked Aubry: Could a building be designed and built at Rice in 11 weeks? Aubry telephoned contractor Gervais Bell, who met them at the site, at the edge of Rice’s football stadium parking lot, the next morning. There, all agreed: It could be done.

The Rice Museum, a wood-framed, wood-floored, gable-roofed shed, was built in five modules that could be separated and easily moved. The museum’s roof and walls were clad in galvanized corrugated sheet iron—the material that gave the Tin House movement its name. Eleven weeks later, the Art Barn, as Rice students instantly nicknamed the museum, opened in time to host K. G. Pontus Hultén’s exhibition The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age. And the next year, a companion building, the Rice Media Center, was built, also clad in galvanized corrugated sheet iron.

The third and fourth buildings in this series were also a pair: the Tin Houses at 507 Roy Street in Houston’s West End, a then-obscure, working-class neighborhood. The defiant common-ness of corrugated sheet iron, its association with buildings that would never be mistaken for “architecture,” made it the perfect medium for exploring the potential of a countercultural design. Aubry’s corrugated metal buildings seemed to express the spirit of an age impatient for change and uncowed by authority.

In 1982, the oil market, which had boomed since the OPEC oil embargo of 1973–74, crashed. With it went Houston’s economy. In 1982, Si Morris retired from Morris Aubry Architects, and Aubry sought to find work for the office beyond Houston and Texas, with some success. Still, he quit the firm in 1985. In 1986, Aubry left Texas to open independent offices in Sarasota, Florida; and Northeast Harbor, Maine, building a practice centered on cultural institutions that continued in the postmodern lineage he’d embraced during the early 1980s. Frances Pew Hayes Hall (1989) and the Baker Museum (2000) at Artis-Naples in Naples, Florida; the Richland Library (1993) in Columbia, South Carolina; and the Selby Public Library in downtown Sarasota (1998) date from this period in Aubry’s career. Bank of America Place on Meeting Street in downtown Charleston, South Carolina, and the St. Regis Aspen Resort in downtown Aspen, Colorado (both 1992), are essays in postmodern contextualism. His most publicized late career work, the control tower at Perot Field Fort Worth Alliance Airport in Fort Worth (1992, with PGAL Architects) recaptured the energy, economy, and precision of his Late Modern work.

Aubry was deeply troubled by the destruction of his Houston buildings. The abusive 2008 redesign of the Central Library, destroying Sally Walsh’s brilliant interiors and banishing Claes Oldenburg’s Geometric Mouse, Scale X, the first modern public art installation in Houston (which Morris and Aubry personally raised funds to acquire) to a back corner, rankled him. As did the MFAH’s demolition of the Glassell School of Art in 2015 in order to clear the site for an underground parking garage. (Steven Holl Architects designed a replacement Glassell School on top of the garage, which opened in 2018). The Tin Houses were demolished in 2011 following their sale by the Menil Foundation to a developer. Rice University demolished the Art Barn in 2014 and the Media Center in 2021. (Diller Scofidio + Renfro has designed a new dramatic and visual arts building for Rice University on the site of the Art Barn and Media Center that pays architectural tribute to the pair.) The KPRC TV Channel 2 Studio of 1972 was demolished in 2017, the entire complex of Barnstone & Aubry’s Center for the Retarded (1966) was demolished in 2019 by the Hanover development company, the half-million–square–foot Brown & Root Southwest Houston Office Building was demolished in 2021, and the University of Houston has announced plans to demolish Stephen P. Farish Hall.

Yet as postmodern architecture is finally gaining the recognition and protections it deserves after decades of disparagement, Aubry’s body of work has seen one preservation success. In 2021, ARO and lighting designer George Sexton & Associates completed a respectful, meticulously executed redesign of the skylight of the Rothko Chapel, as well as other enhancements, to mark the chapel’s 50th anniversary. Aubry was consulted by the chapel’s executive director, David Leslie, during the restoration process.

What stands out about Aubry’s career is how his Late Modern buildings—precise, elegant, subtly witty—channeled the enthusiasm, assurance, and bravado Houston exulted in during the 1970s. It is this Houston of the imagination that Aubry’s architecture materialized, which is why the loss of the designer, as well as his works, is so painful.

Stephen Fox is a Fellow of the Anchorage Foundation of Texas. He is a lecturer in architecture at Rice University and the University of Houston.