We live in San Francisco, a city once known for its counterculture, labor unions, hippie communes, and offering of sanctuary to those that felt like outcasts. But decades of cultural consolidation around the tech industry and the increasing commodification of the city has flattened its diversity. Watching kids play in small backyards, separated from the kids they hear on the other side of the fence is a surreal twist of fate and at odds with the historic, collective ethos of the city.

The fence, which registers the property line, prevents the sharing of space. We suspect that beyond our own kids, countless others are isolated in small, repeated backyards across the city, looking for others to play with. This physical and social division along the lines of private property, however, is more than a question of taking down the fence; it is a problem related to typology and a city drawn from speculation and division. This is the point of departure for Lots Will Tear Us Apart, a conceptual housing proposal for San Francisco designed by our practices, The Open Workshop and Spiegel Aihara Workshop (SAW).

Speculation and segregation of space in San Francisco had already begun in the 19th century. The city’s rapid urbanization during California’s gold rush (1848–55) was aided by the gridded division of land into commodifiable plats. Disregarding site variations and topography, among other factors, the grid was deployed to produce transactional economic value where none previously existed. On these lots, repeatable housing typologies were utilized to quickly house the growing workforce.

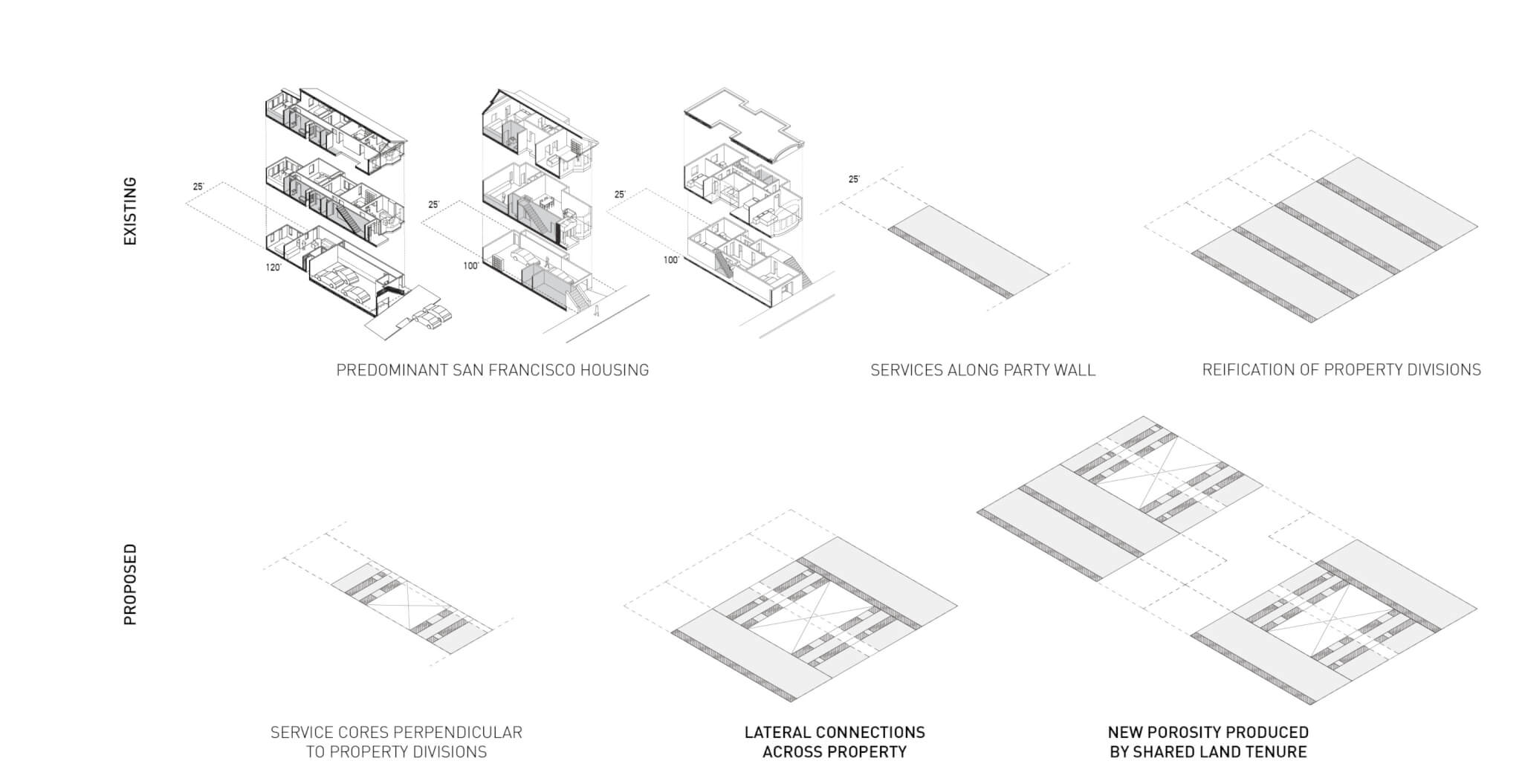

The Victorian type dominated San Francisco’s urbanization and was easily realized on the standard lot, 25 feet in width. Beyond its ornamental variations, the Victorian type is a simple array of rooms situated along a linear corridor that also contains services like plumbing and structure. Rooms often stepped away from the property line along the adjacent lot at the front or back of the house to allow light to penetrate the interior spaces. This stepping did not proactively acknowledge adjacent lots to create shared space; instead, it eliminated the possibility of anything of consequence being placed on the adjacent lot, much less having any productive relation to it. One ramification of the narrow standard lot width is that it casually coerced the predominant housing typologies to pack services, circulation, and structure along the party wall(s).

Ultimately, this act of consolidating services and structure—some of the most permanent building elements—along the lot line reified private ownership divisions. Even though many of these homes have been internally updated over the past century, these complex services and structures often remain along the lot line. Here, the relationship between a housing typology and lot size establishes a system of division. Can this relationship be reoriented by reclaiming housing typology as a catalyst for a more collective city?

In architecture, “type” refers to the common and essential characteristics of a building. Working with type is less about what something looks like and more about how an aggregation creates a system over time. In this way, type acts as a mediator between architecture and the city. Typology in architecture is more often associated with housing than other programs, as housing is usually produced through repetition, embedded with constraints. These constraints range from quality of life (access to light and air), life safety (egress, fire separation, etc.), building systems (stacking plumbing, mechanical), to the financialization of space (maximizing leasable/salable square footage). Typology in housing is not just a spatial product, however, it is also a social one: single-family homes deploy type to repeat the social unit of the nuclear family, which was to be reproduced ad infinitum. And, of course, through repetition, housing typologies aggregate to form the fabric of the city.

Is the contemporary project of housing type sufficiently concerned with the results of this aggregation? Today, typological “design” in San Francisco largely draws from parameters that are reactionary rather than anticipatory, meaning that they address constraints at the scale of the lot but do not proactively consider how they multiply into the form of the city. The large financial pressure on land in San Francisco is the most influential factor in present day design of housing typologies: It demands designers and developers alike to maximize zoning envelopes and salable square footage. These are undoubtedly reasonable considerations when designing housing, but how can we go beyond these constraints to reclaim typology as a project that can reconsider the physical and social form of the city? This is not a new question.

Consider, for instance, the alphabet housing typologies that urbanized the core of many American cities: Through their aggregation, they produced continuous street walls, reciprocated light wells and courts, and formed an attitude of resigned typological anticipation of the adjacent lot. By exceeding the individual lot and household, type allows architects to consider the city—the aggregated urban fabric—rather than solely the residence, as a project.

Cities are surely more than the sum of their parts; they are systems based on multipliers. We understand typology fundamentally as multipliers, or designs that produce multiples to form a cogent whole. Architects must shift the debate on housing access away from solely supply-side economics to the production of a dense, collectivized city. Going beyond the found conditions of the accidental whole or incremental designs for one-off lots, can we reverse engineer a project for a more collectivized city reclaiming housing type as an architectural and urban project? Can we design new housing typologies to proactively anticipate adjacencies and produce a more collectivized city? Can we leverage typology to shift the ethos of private ownership to one that is more shared?

Lots Will Tear Us Apart, reimagines the standard San Francisco lot, 25 feet wide by 100 to 140 feet in depth. The proposed type is anticipatory, and in time would reorient the grain of the block to overcome the stubborn reification of property divisions.

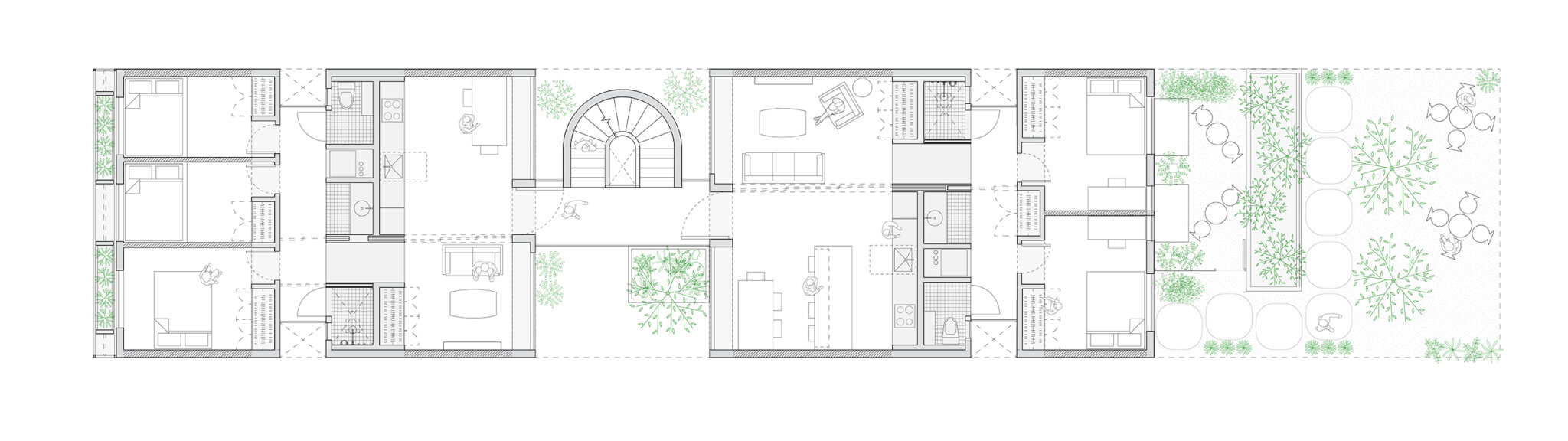

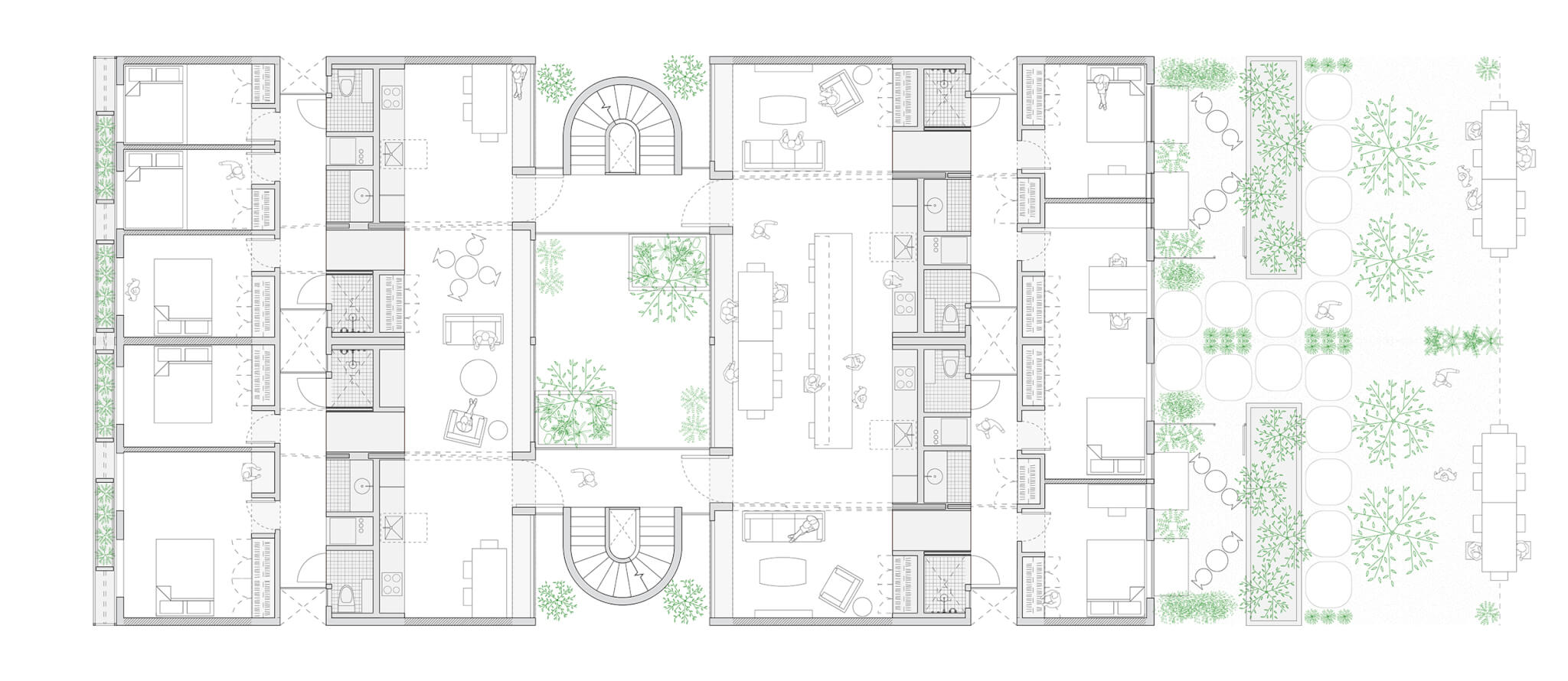

To do this, we must liberate the property line. This starts by consolidating the most complex building systems and structure into efficient prefabricated cores and orienting them perpendicular to the parcel. By emancipating the party wall, the typology enables the possibility of connecting across and between lots. Instead of addressing the community on only two sides—the front and back—one can now engage on all four. A series of simple sliding and easily constructible/demountable partitions span between these cores to provide flexible forms of occupation that acknowledge a range of family forms like co-living, intergenerational living, and found families—extending beyond the nuclear family.

For instance, an efficient array of three bedrooms could convert to two larger rooms or a single suite. Built from cross-laminated timber spanning between the cores, the party walls wouldn’t be structural, which enables a myriad of configurations that bridge across lots. In even the most basic aggregation, two adjacent lots may join laterally, allowing for larger units as well as collective living arrangements structured around a central courtyard. Or, if joined back-to-front, a generous access way through the block would offer the rear yard as a space to be shared with the city. Children will not just hear one another, but join across lot lines to play together in combinatory yards.

Over time, Lots Will Bring Us Together would infuse property divisions with renewed interconnectivity, communal courtyards, and cross-block cuts. It could even challenge the isolation that single-family homes can create. While the expanding pressures of building codes and land value have disempowered an architect’s ability to interrogate type, we think it is the best way to reclaim the project of the city for architects. We can do so much more than just live next to one another—we can live together.

The project team for Lots Will Bring Us Together included Neeraj Bhatia, Andrew Bertics, and Duy Nguyen from The Open Workshop and Jeremy Ferguson, Shinji Miyajima, and Dan Spiegel from SAW.

Neeraj Bhatia is the founder of the architectural urbanism practice The Open Workshop and associate professor at the California College of the Arts where he directs the Urban Works Agency.

Dan Spiegel is a cofounder of the hybrid architecture and landscape architecture practice Spiegel Aihara Workshop (SAW) and continuing lecturer at the UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design.