With almost 12,000 athletes from 45 Asian countries and regions participating in its latest iteration in Hangzhou, China, the Asian Games is the world’s largest sporting event outside of the Olympics. Like the Olympics, the event’s host cities have long struggled to activate their venues and sites after the festivities. Nobody wanted a repeat of Beijing 2008, where Herzog & de Meuron’s celebrated “Bird Nest” now sits empty much of the year, or much less a rerun of Athens, where venues from the 2004 Games have largely been abandoned.

The most recent Asian Games, branded as Hangzhou 2022, took place last fall. (It was delayed a year due to COVID-19.) Hangzhou, a city of over ten million people southwest of Shanghai, hosted 481 events in 56 competition venues, including an 80,000-seat, lotus-shaped main stadium by NBBJ.

One of the most effective clusters was devised by a New York–based team of architects, Archi-Tectonics; landscape architects !Melk; and engineers Thornton Tomasetti. On the northern edge of the city, the 116-acre, seven-venue Gongshu Canal Sports Park fuses flexible venues and inhabitable landscapes to deliver a site that will thrive in the city well beyond the games. “We said from the beginning that this park should be about the future of the neighborhood,” Winka Dubbeldam, founder of Archi-Tectonics and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, told AN.

The three firms developed their scheme for the project competition before working with local offices to complete most of the landscaping and engineering. The key venues—stadiums for field hockey and table tennis—sit at either end of the mile-long, rectangular site, which was previously crisscrossed by agricultural canals and bisected by a six-lane roadway. The canals were rerouted into a new river that spills into a new lake, freeing up land for buildings and green space, but the roadway remained intact.

To cross this divide, the team proposed the Village Valley Mall, a recessed canyon that meanders for a half mile between the stadiums and beneath the street. It is dotted with circular, green-roofed pavilions that incorporate shops, restaurants, and cafes. All of this is supplemented with plant-filled outdoor gathering areas. This has become the project’s social heart, and the site’s divisions have been further linked via snaking pedestrian bridges—two over the roadway and six over the river—that inject a sense of kinetic excitement.

The Valley Mall, noted !Melk founder and principal Jerry van Eyck, was inspired by Rotterdam’s Beurstraverse, a sunken, 1990s shopping complex that helped connect that city under a major road. “After growing up in Rotterdam and working there for many years, this came as a sort of natural move,” van Eyck said. Dirt from the excavation helped create hills and other landscape features across the site, keeping the overall project “zero earth,” meaning no soil left the site.

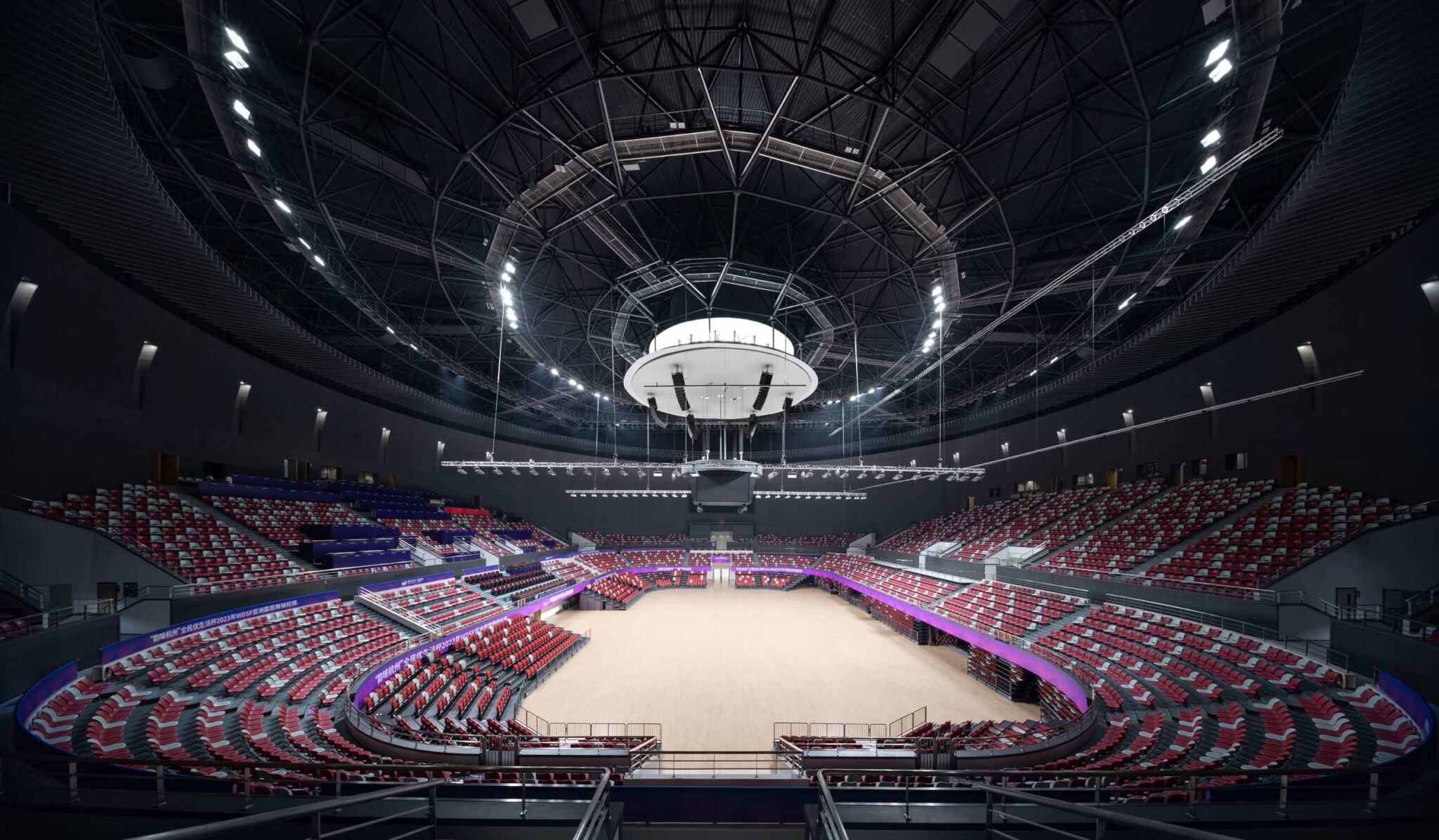

The site’s athletic venues anchor opposite ends of the promenade. The centerpiece is the 5,000-seat table tennis arena, which also functions as an entertainment venue. Its oblong form, Dubbeldam said, is the result of two intersecting ellipses, creating a “wobbly” design that carves out surprising interior spaces.

One diagrid facade of flat glass units looks out toward the park, while the opposite is covered in overlapping brass shingles evocative of fish scales, suggesting a mysterious object like Hans Scharoun’s Philharmonie Berlin, Dubbeldam’s favorite building. At the center of the arena, a long-span, steel-trussed “suspen-dome” structure creates an uninterrupted central space faced in bamboo that can be transformed from arena to amphitheater seating. The “suspen-dome” tapers beyond this core to cover the flanking support spaces, including lobbies, ramps, stairs, and a VIP viewing area. Beyond table tennis, the facility was used for breakdancing, marking the first time the sport has appeared at the Asian Games. It’s also designed to host cultural events and performances.

At the opposite end of the site, the oval-shaped, 5,000-seat field hockey stadium is set about 16 feet into the ground, so it appears to be emerging out of the landscape. A soaring mesh roof covers the seating area and shades the field beyond. This is supported by a single arched steel beam, and concrete abutments keep it in tension. The gesture gives “drama and emotion,” observed Scott Lomax, senior principal at Thornton Tomasetti. “It’s a symbol of the importance of this project.” The cast-in-place concrete seating area is accessed via a glass-wrapped lobby. Its openness, combined with that of the unwalled playing field, helps the venue connect more intimately to the site.

Sustainability is built into most of the plan. The wetland landscape, crisscrossed by boardwalks, porous pathways, playgrounds, and elevated areas, is filled with local vegetation—as part of a required “sponge city” approach, it is designed to absorb runoff and prevent flooding. The river and lake, which serve as sites for kayaking and other recreation, help collect water. Islands in the river are scenic elements that also clean and oxygenate the water by speeding up currents. From above, one can see that 85 percent of the site is covered in planted surfaces or water.

The buildings are green, too. The table tennis stadium achieved Green Building Evaluation Label 3 Star, the highest level of sustainability in China, equivalent to LEED Platinum. Its diagrid structure and planar glass helped remove 1,130 tons of steel from the effort, according to the team. The park’s several green roofs total about 690,000 square feet and can release around 83,000 kilograms of oxygen and absorb nearly 115,000 kilograms of CO₂ annually.

The neighborhood around the project, which was already humming, now sports many high-rises, and real estate values have soared, Dubbeldam observed. Locals, who got to know the project before the games commenced, regularly use the park and the venues, she added. The size of the complex and the designer’s prioritization of visual and physical connectivity help it feel like part of the city. There is no concern that this will become a left-behind area. “If you give people something precious, they will treat it as precious,” said Dubbeldam. “They treat it like a permanent inhabitant of their city.”

Sam Lubell is an editor at large at Metropolis and has written more than ten books about architecture for Phaidon, Rizzoli, Metropolis Books, and the Monacelli Press.