Creatures are Stirring: A Guide to Architectural Companionship | Joseph Altshuler and Julia Sedlock | Applied Research + Design Publishing | $30.00

Under late capitalism, the desire to experience connectedness between mushrooms, potato plants, or ant colonies is an understandable feeling. Neoliberalism has created its own form of self-alienation, both from nature and society at-large. Responses to this atomization have appeared in myriad books since the 1990s, whether they be Graham Harman’s ruminations on object-oriented ontology (OOO), or Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the rhizome. These concepts have in turn been translated by architects with varying degrees of success. Might revisiting the desires behind these ideas of interspecies connectedness teach architects how to translate them more coherently into architecture?

In Creatures are Stirring: A Guide to Architectural Companionship, Joseph Altshuler, an assistant professor of architecture at the University of Illinois, and designer and community advocate Julia Sedlock have assembled a book of ideas around how we can use architecture to address desire and alienation. The creatively structured, multi-author book is billed as a “guide to architectural companionship.” Its essays, illustrations, diagrams, and memoirs are offered not as a manifesto nor a prescription, but as examples of exercises in jazzing up one’s worn-down capacity for fantasy. For many, this has been considerably weathered by the tiring condition of the architectural world under late capitalism.

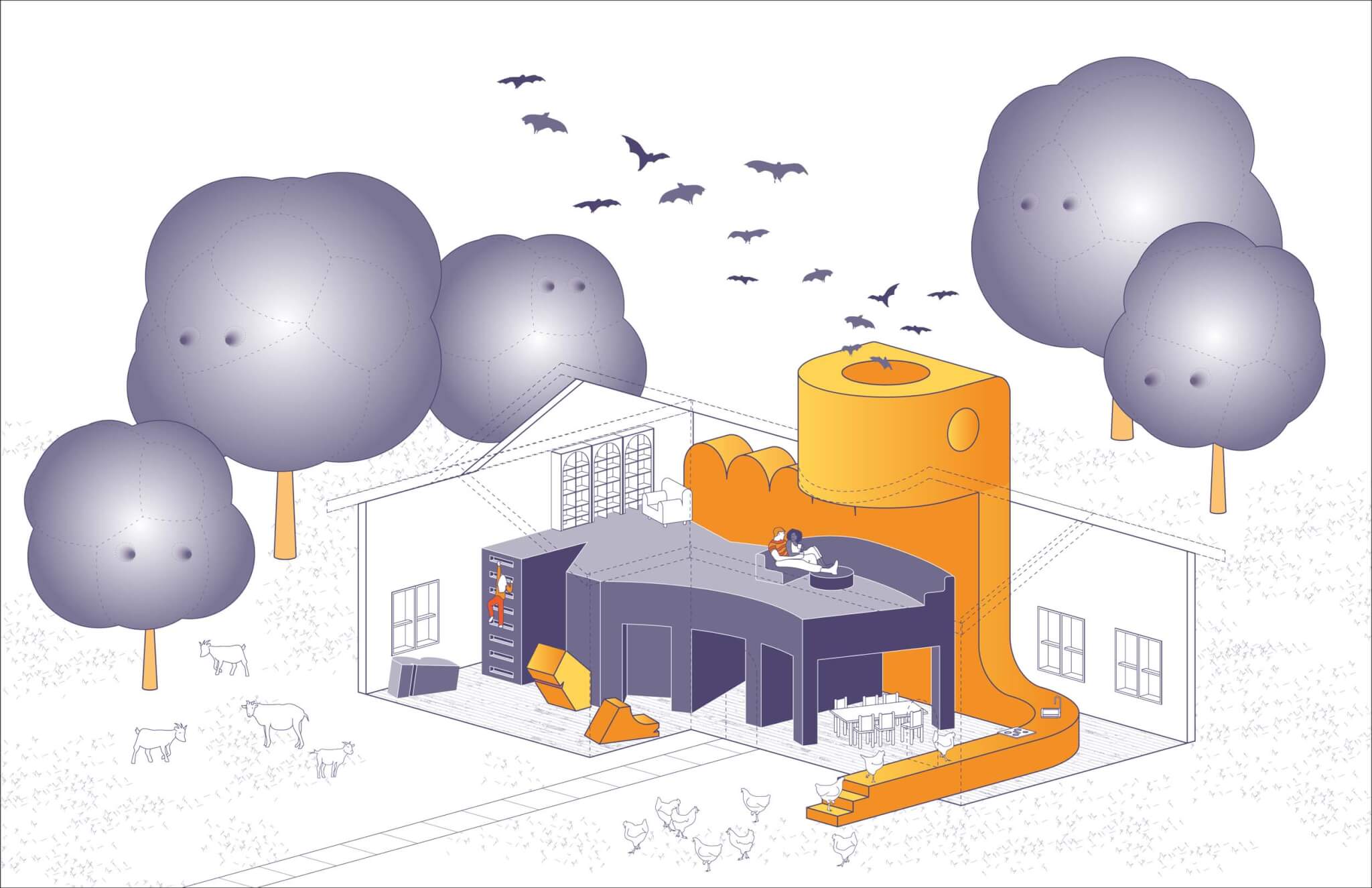

In its chapters, an electric band of characters emerge: marsupials, a brave raccoon and a clever dolphin, Stanley Tigerman, the Trix Rabbit (of breakfast cereal fame), and Donna Haraway each have cameos. These characters offer a variety of ideas for how a building can be a “creature” or even creaturely—a term which the various authors hesitate to unilaterally define as their project is reflective and far from systematic. Rather, the term allows buildings to have selves and relationships but avoids the rigid organic/inorganic binary in favor of a more fanciful territory.

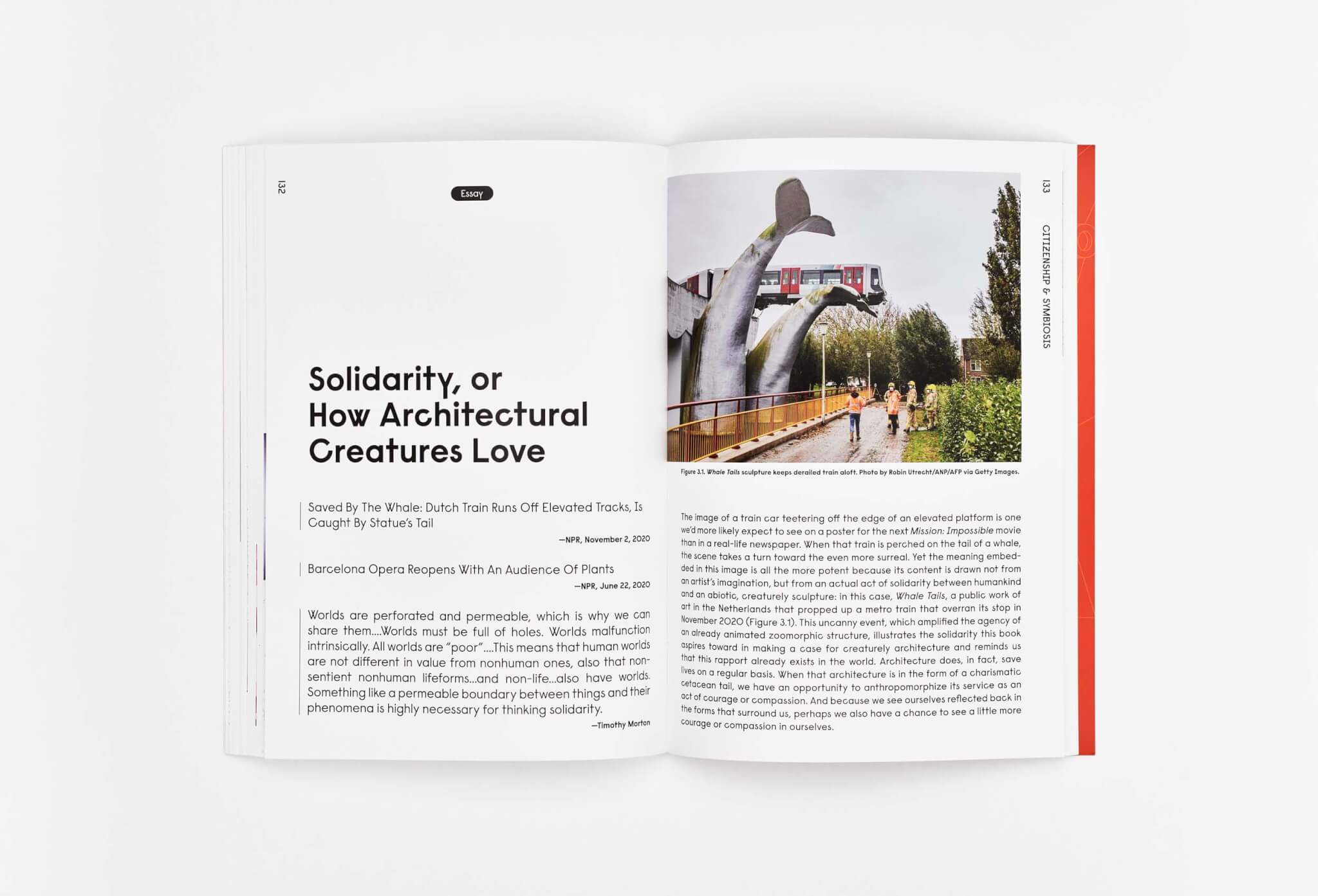

As contributors Steward Hicks and Allison Newmeyer suggest, it is not the formal dimensions of a building which make it a creature. Thus the aim is to “shift the conversation from the structure itself onto the effects the structure has on its occupants and viewers.” The term “creature” can describe the cheeky quality of a zoomorphic or anthropomorphic building, but it can also imbue any building with its own selfhood, allowing us to form relationships with it. The book’s purpose is less to classify or define the creaturely and rather to reinvigorate one’s fantastical faculties, which we need in order to make “friends with architecture” in the first place. From there, politically impactful stances can be taken: to think of buildings as our friends would be to repair and reuse them, even when they are no longer fashionable.

Given the book’s apparent orientation toward the non-human, one might be forgiven for expecting something more squarely in the register of new materialism, a field which often bumps into actor-network theory and object-oriented ontology. These are different names for related theories which seek to relieve anthropocentric bias by elevating all things—buildings, creatures, humans, water, you name it—into one decentralized, non-hierarchical network. The risk of this view is that it can flatten the being-hoods of both humans and non-humans into indistinguishable, politically void nodes of interacting matter.

Creatures are Stirring resists this degree of over-flattening, to the relief of the meme collective Dank Lloyd Wright, who admit as much in their foreword, one of ten free-form blurbs preceding the text from a variety of architectural thinkers: “Sometimes it’s easier to sustain a conceptual relationship with a creature than it is to build a relationship based on respect with other humans, which is kinda fucked up. Still, we trust in the belief that any attempt to locate agency in nonhuman actors will help expand human consciousness or expand such advances.” This is the trust one must have to appreciate Creatures are Stirring. New materialist theories can serve as excuses for political passivity, but this situation is even more salient in architecture, wherein posturing to “listen to a brick” like Louis Kahn might preclude listening to other urgent cries for justice. As Dank Lloyd Wright points out, the new materialism-adjacent ideas herein are not intended to be the “escape” that new materialism often is for architects, but “an amplification of what is here, now.”

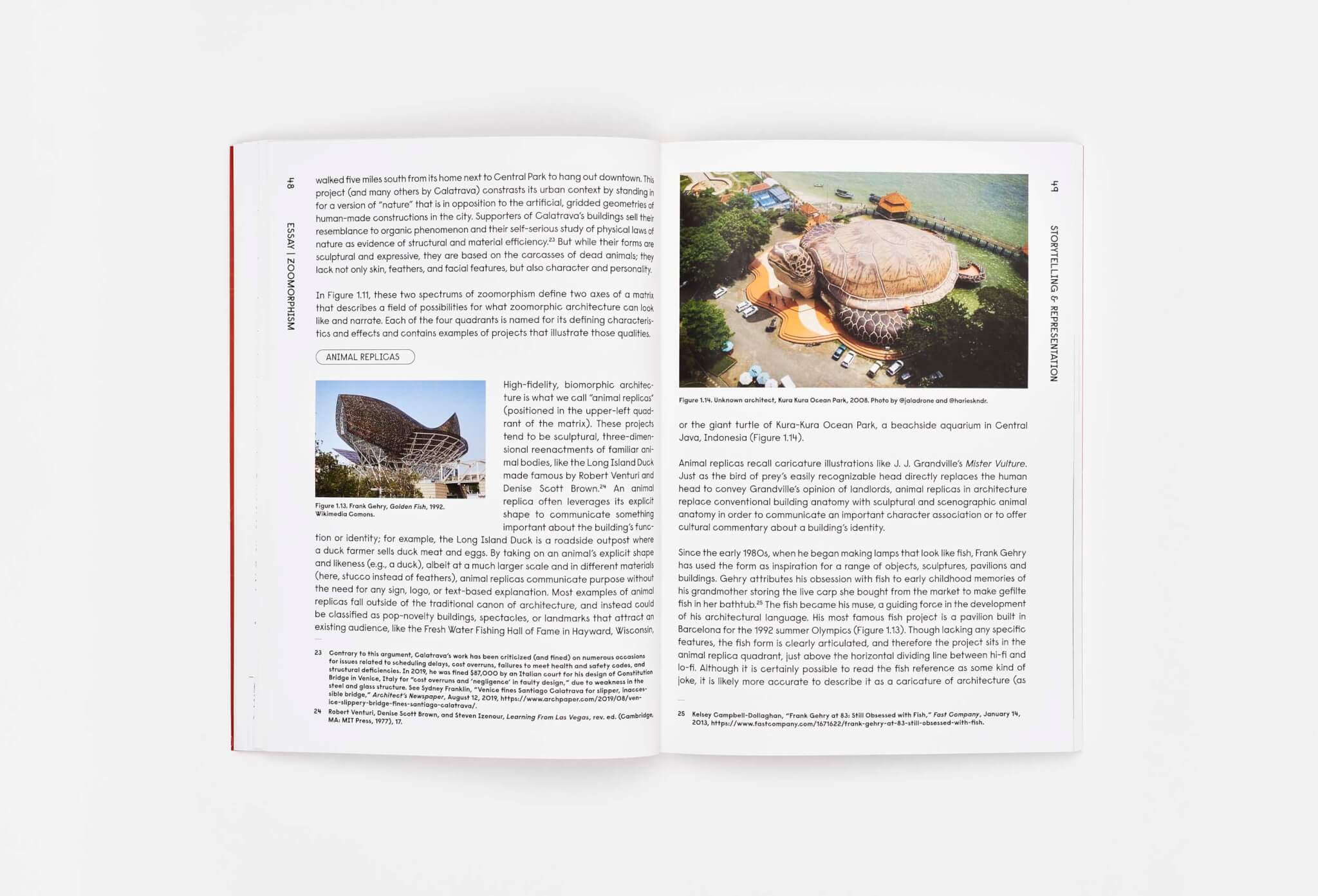

The significance of zoomorphic architecture has been well established, considering the canonical status of Frank Gehry’s multitude of fishy structures, Archigram’s Walking City, and of course Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown’s duck dichotomy. But the authors show how buildings don’t have to resemble creatures to imagine relationships—even the supposedly highly rational Villa Savoye “might easily be seen as a stealthy crab-like creature ready to shuffle away across the lawn at the sight of first trouble.” Their desire is not to create a taxonomy of building creatures for taxonomy’s sake, but to riff on the idea so that others can borrow the format and produce their own riffs, like any good meme template.

The diagrams which appear at chapter intervals reference Rosalind Krauss’s 1979 structuralist diagram, designed to forge a language for talking about sculpture when the term’s flexibility (“sculpture” could now encompass holes in the ground or bricks on the floor) had rendered it a semantic void. Creatures are Stirring may be optimistic in its offerings of memes as formal innovations, but the utopian dreams of architectural creatures do not always have happy endings. Sometimes, imaginative projects should really stay imaginative.

Ant Farm’s speculative Dolphin Embassy, a space designed for dolphin-human communication, is a boatload of fun, but when a version of this experiment became a reality in the NASA-funded scientist John C. Lilly’s laboratory, poor Peter the dolphin really ended up with the short end of the stick. Peter, recruited as the experimental subject, cohabitated with a young scientist in a flooded lab building. Apparently, he fell in love with her, and when the experiment was halted, he committed suicide by neglecting to come up for air. If this tragic conclusion is omitted, the premise is utopic for the naïve new materialist: Animals and humans can learn to cohabitate and share affective engagement! Ant Farm’s silly idea really worked! MoMA’s recent exhibition Emerging Ecologies, which comprised a postmortem for 1960s and 70s cybernetic pipe-dreams, neglected to mention the tragedy in their juxtaposition of the Dolphin Embassy next to a playful image of Peter nudging the scientist’s foot as she talks on the telephone. When contributor Joyce Hwang discusses the project in Creatures are Stirring, the whole story is told.

The fact that history and temporality impact how we interact with building-creatures is demonstrated in how the voices in the book speak from 2020 and 2021, a terrifying time which carved open a space of possibility for reimagining business as usual. In 2024, it is useful to recall this space to remind ourselves of just how radically the pandemic changed how many people feel about their relationships with architecture. After all, if you are stuck inside, you might seek a guidebook on how to befriend your building for pragmatic and not idealistic reasons. Revisiting the creaturely moments of this era could serve as a reminder to not let “a serious crisis go to waste,” as a catalyzing or galvanizing force for change.

In today’s climate and social emergency, buildings are never neutral. We might as well take this moment to befriend the buildings we have already, and imagine possibilities that may otherwise be invisible to the grown-ups.

Kathleen Quaintance is a PhD student at Yale University working on craft, technology and textiles.