Neeraj Bhatia is the founder of The Open Workshop, an architectural practice based in San Francisco that is furthering design research toward collective living and the urban commons. Bhatia and AN contributor Palmyra Geraki discuss the latest edition of the Workshop’s publication, New Investigations in Collective Form, as well as Bhatia’s ongoing research and the values that ground an emergent body of work.

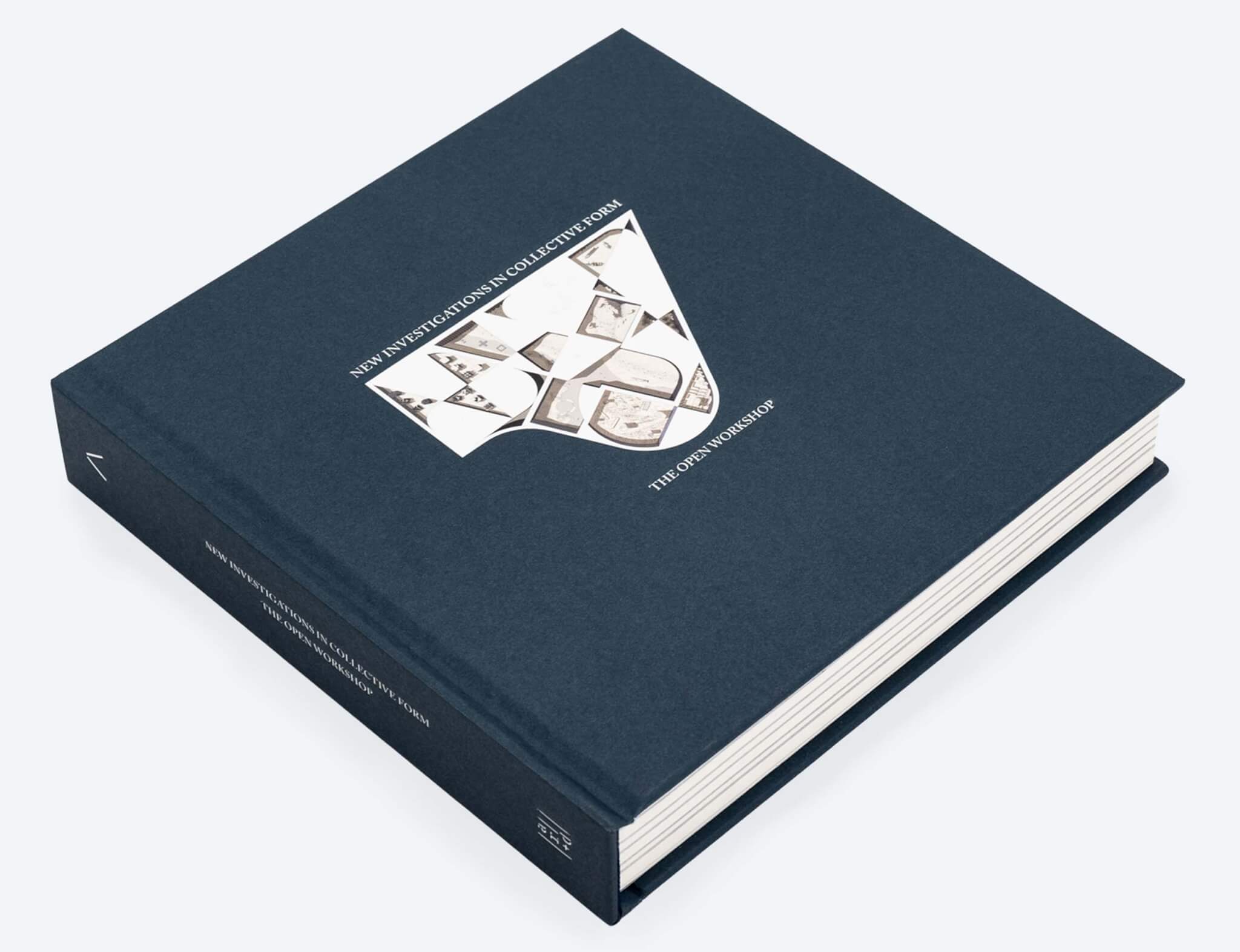

Palmyra Geraki (PG): In 2018, the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA) in San Francisco hosted an exhibition of work by your practice, The Open Workshop. The exhibition shares a title with your most recent book that followed it: New Investigations in Collective Form. How did the book come to be?

Neeraj Bhatia (NB): It’s important to note that the exhibition was in a building designed by Fumhiko Maki, and the office has always been taken by an early text that Maki wrote titled Investigations in Collective Form. In it, he’s grappling with the future of the city in the wake of transformations to the formal and social structure of society, and trying to understand the glue that bonds us together. We wanted to build the exhibition, and eventually the book, around similar questions also at the core of our practice.

I feel that collectivity and the solidarities it catalyzes are the most critical weapon against forms of precarity. The exhibition itself was visual, immersive, experiential, performative—it was an exercise in practicing collectivity. We used the medium of the exhibition to consider how the individual, collective, and nature are part of an ongoing negotiation, but tried to limit the amount of textual information.

The book, on the other hand, allowed us to provide more background on the ideas and the research and to involve a series of interlocutors that form a constellation of influences to the practice. It attempts to capture a series of ideas in formation, conceptualized by a young office trying to make sense of how the discipline can intervene in an increasingly complex and entangled world.

PG: The first edition of the book sold out quickly. You recently launched a second edition, which features some changes—most notably the inclusion of three new projects that were completed after the original publication. What prompted this content expansion?

NB: When you get an invitation as a young practice to exhibit your work, it’s a privilege to have that moment to stop and reflect on what you’ve been producing and see patterns in the work. Through that process, we extracted the techniques of creating collective form that organized the book: Articulated Surfaces, Soft Frameworks, Living Archives, Rewiring States, and Commoning. Of course, once these themes become foregrounded, they change the way you work because you’re able to see them in everything you do.

With these three new projects, there was more self-awareness. And perhaps that’s one of the reasons why they’re so emblematic of the themes that organize the book. Our project for the 2019 Seoul Biennale looked at the politics of archival space and questions of power related to the archive, but also how the archive can be reclaimed as a place for public assembly and empowerment.

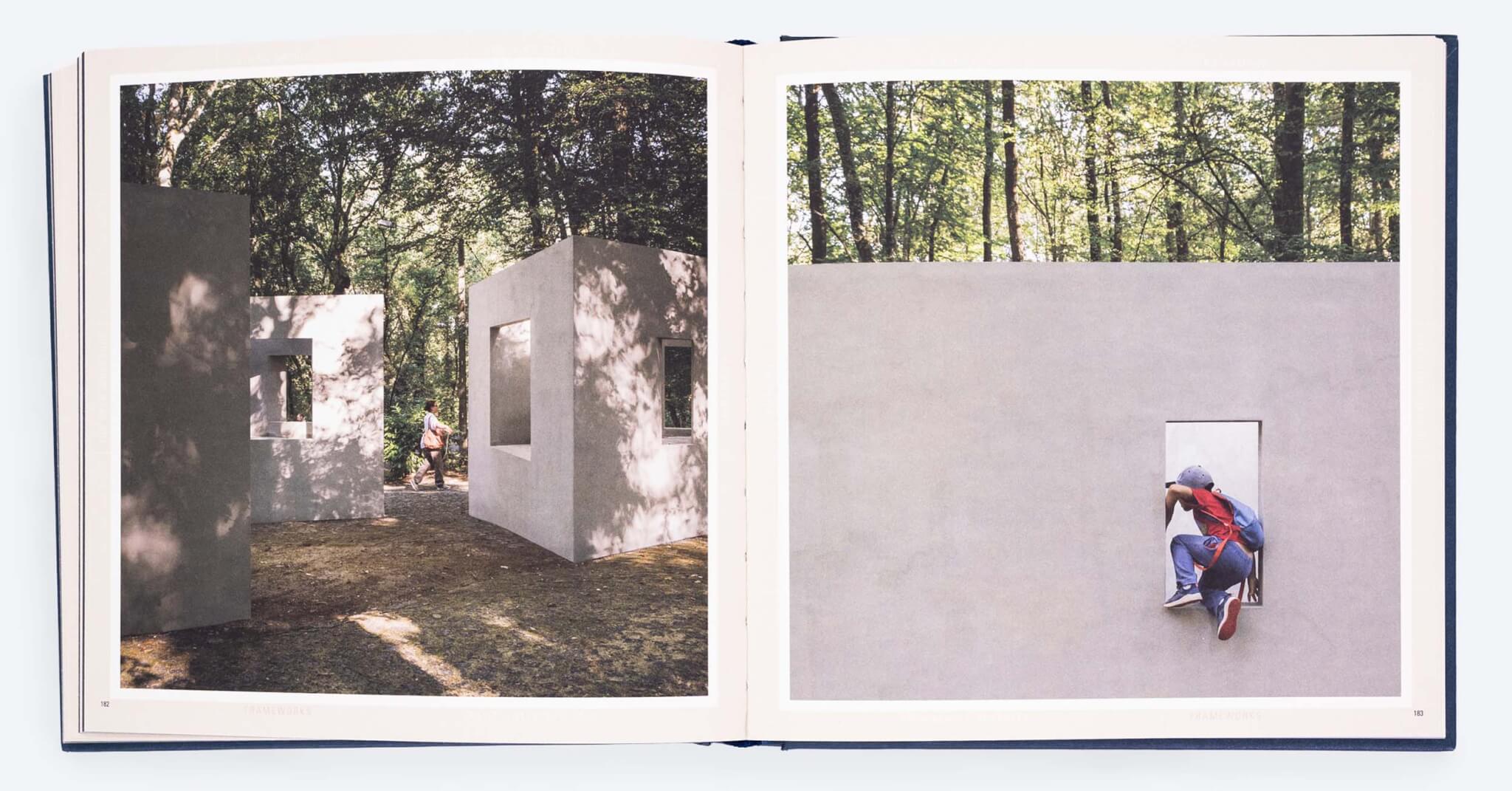

Our Venice Biennale project (2021) built on research I’ve been doing jointly with Antje Steinmuller, a colleague at California College of the Arts, investigating, documenting, and analyzing a series of communes and collective living projects in the Bay Area. It was the first time after years of doing research on collective living that we started translating our ideas into designs.

For the 2021 Chicago Architecture Biennial project, we interfaced with about 30 mutual-aid and solidarity organizations in Bronzeville on the south side of Chicago to produce a series of broadsheets, spotlighting the work that they’re doing in the neighborhood in an effort to see synergies between the work of various organizations and scale up their work. Beyond being emblematic of the book’s themes, for me, these three projects are also starting to shift more into material translations of our research.

PG: How much of this thematic framework existed in your work prior to the exhibition and the book, consciously or subconsciously? In the context of a design research practice, where the impetus for the projects is typically internally generated, how important is it that you are conscious of these broader questions before embarking on a project?

NB: There are things we do as designers that are based on a framing of interests and politics that sets a trajectory. And part of design is always intuitive, non-linear, and inquisitive. I like calling these projects experiments as they are tests—they begin with questions and also end with (very different) questions.

The office is named after a theoretical concept by Umberto Eco, “the open work,” which attempts to address a very difficult position that designers find themselves in today: On the one hand, our role is to design things, which comes with an inherent disciplinary desire to control and order the world. On the other hand, the world that we’re facing increasingly reveals the futility of those actions.

For us, the naming of the practice was very much rooted in a question of how “the open work” could materialize in architecture—giving new grounds for design agency while also leaving an openness to not control the traditional subjects of architecture—but also in the environment and human subjects.

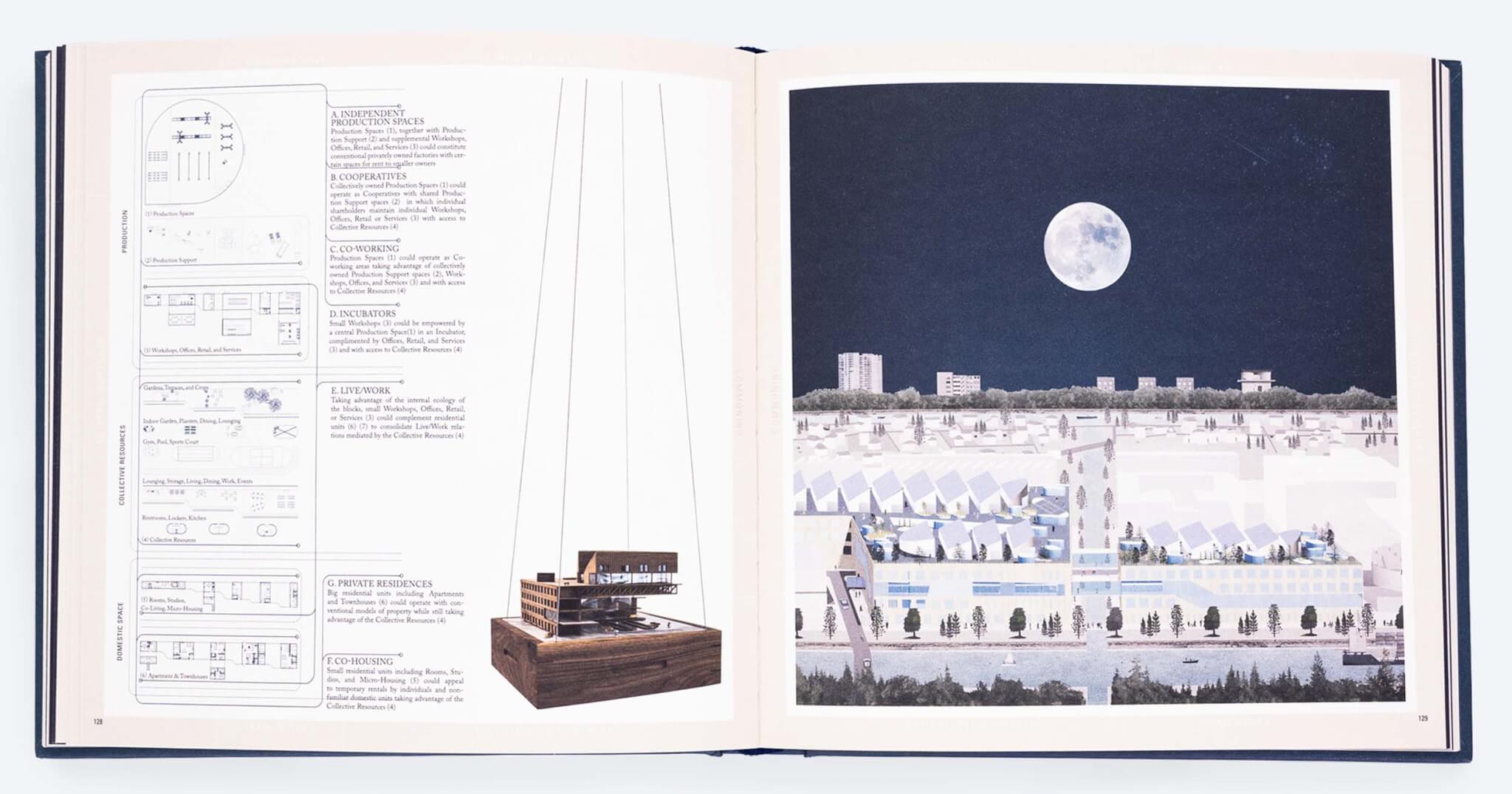

While Maki’s treatise centers on three techniques of collective form (group form, compositional form, and the megastructure), they are very much form-based. Two of our techniques, Frameworks and Surfaces, are also form-based, but the three other techniques go beyond. Rewiring States is really time-based and so is the Living Archive but at a very different timescale. The last theme, Commoning, was much more of a programmatic theme and a form of action.

One of the evolutions in our work is that we’re interested in form and aesthetics, but also increasingly interested in invisible protocols—whether of governance, land ownership, stewardship, economics, etc. that inform form. Our interpretation of collective form expands the notion form to also include forums of assembly.

PG: There is a very intentional approach to representation in your work. What is the importance of maintaining formal and representational integrity in the context of an open work?

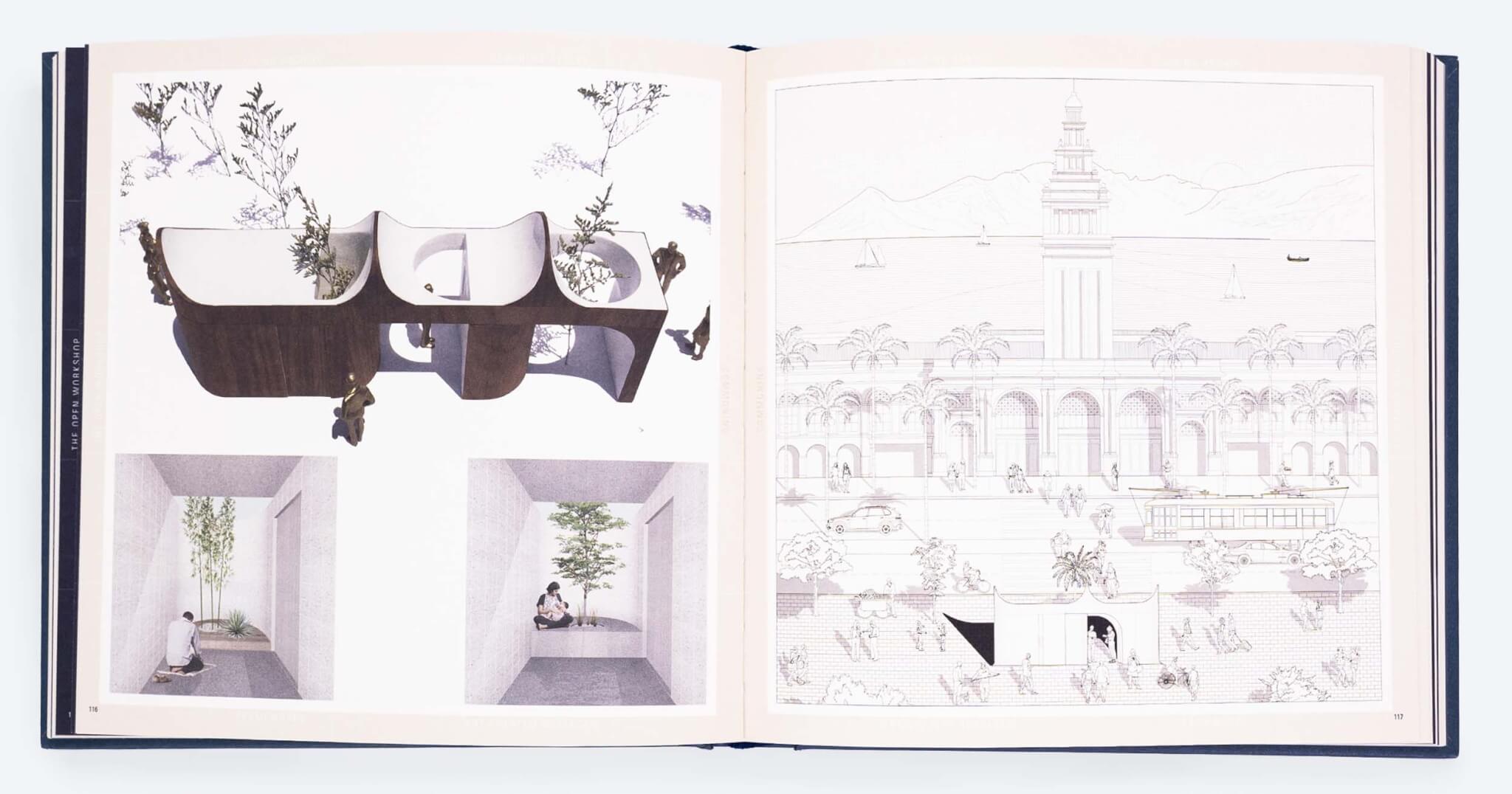

NB: In The Open Work, Eco talks about how the degree of openness is still framed within a world intended by the author. For us, it’s about starting to share authorship, including new subjects in the design process, and in the final result. The work of the office, I would say, is much more interested in background environments, not the kind of foreground architecture that one might be exposed to in magazines. In the office we use representational techniques to give just as much emphasis to the social and environmental factors in the drawings as the form itself, and, by doing so, to give these subjects a voice in the representation.

PG: How has your teaching influenced your practice?

NB: For any designer that teaches there’s hopefully going to be an influence both ways. A couple things I can say maybe more generally about California College of the Arts, where I teach, is that we are an architecture program in an art and design school, which is fairly unique. Being in a school of art and design in the Bay Area is like being in a school of activists, because artists on the whole are much more politically motivated and tend to clarify their politics through their work. Being in the vicinity of art practitioners daily reminds all of us that we don’t need to accept the systems we inherit—that we can push back. The generation that’s coming out of school is eager to think about how the discipline can have more agency. I’m really inspired by that energy and by the idea that the role of an architect is almost that of an activist, and an advocate simultaneously that of designer.

PG: I’m interested in the idea of audience, because it can be interpreted in so many different ways. Earlier, you mentioned that a design research practice mostly doesn’t have clients in the traditional sense. At the same time, a lot of your projects are very grounded; you’ve worked with communities or local environments. Whom do you see as the audience for your work as well as the book?

NB: The book’s audience is likely architects, particularly architects that are interested in research and in questioning how they can have more agency to address issues that are unfolding in the world. I think there is a growing group of architects that are interested in social and ecological issues as well as in form and aesthetics, and see those as part of the same question.

The audience for our work more generally goes beyond architects and urbanists to also include policymakers and governments as well as community members and groups. Engaging those three audiences at the same time has been critical for the office. I’m not interested in problem-solving for any of these audiences but rather problematizing the issues and offering the tools to help understand what is at stake. If you read between the lines, a question that comes out of this type of work and out of the book is: How do we advocate for a new type of client and a new type of project scope? The book uses design work to elucidate how we can collectively expand the role of the architect and thereby our agency in addressing a precarious world.

Palmyra Geraki is an interdisciplinary architect, educator, writer, and editor. She is the founding principal of PALMYRA, a design practice working across disciplines, scales, and typologies, and an assistant professor at University of Wisconsin Milwaukee.