“The final solution to housing for the masses is that it be a government function such as streets, highways, sewers, water, subways, post offices, Ozarks, etc. It is too vital for the needs of the people to be subject to the profit motive.”

—Herman Jessor

New York City has 7,197 cooperatively-owned buildings that contain a total 364,720 homes. Over the course of his 60 year career, architect Herman Jessor designed 40,245 of those limited-equity units, composing 11 percent of the city’s total supply of cooperative housing. In a recent profile celebrating Jessor, critic Owen Hatherley described him as “the most important radical architect you’ve never heard of.”

Herman Jessor’s work includes the Bronx’s Sholem Aleichem Houses (1926) and United Workers’ Association Houses (1926-29); Amalgamated Dwellings (1930), Hillman Houses (1951), East River Houses (1956) and Seward Park Houses (1961) in the Lower East Side; Penn South in Chelsea (1963); Amalgamated Warbasse Houses (1965) in Coney Island; and Rochdale Village in Queens (1966). Jessor’s buildings were often built hand-in-hand with socialists and radical trade unionists fighting for a fairer metropolis amid the violent throes of industrialization and McCarthyism. And thanks to his efforts, despite myriad privatization attempts, Rochdale Village stands as the “largest Black-majority housing co-op in the world.”

In 2023, Herman Jessor’s boldest feat turned 50 years old: Co-op City. There, 15,732 homes are spread across 35 high-rise towers and seven low-rise townhouses on a sprawling 320-acre site in the north Bronx. The Ville Radieuse–inspired ensembles coalesce around shared green space, bike paths, a co-op grocery store, shopping center, schools, and playing fields. The estate was built on top of a former amusement park, Freedomland, and was backed by Governor Nelson Rockefeller alongside Robert Moses. In plan, Co-op City’s towers are cross-shaped: This allows for every unit to have entry foyers, cross breezes, balconies, bay windows, and eat-in kitchens—features that millions of people living in New York’s damp tenements had been historically denied.

And throughout the years, myriad legendary New Yorkers have passed through Jessor’s flats: U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor called Co-op City home as a teenager. The legendary labor leaders W.E.B. Dubois, Emma Goldman, Audley “Queen Mother” Moore, Paul Robeson, and Pete Seeger were famous for moving in-and-out of Amalgamated Cooperative Houses in the Bronx, a milieu otherwise known as “the commie coops.”

Penn South in Chelsea is the childhood home of the late Marxist David Graeber, who longingly described the place as his “only permanent address” before his death. Graeber also used to attribute his radical politics to the place where he grew up, and the trade unionists who lived there. Even Marc Chagall lived at Sholem Aleichem Cooperative Houses after fleeing the Nazi invasion of Paris. The bubbie in Joan Micklin Silver’s 1988 rom-com Crossing Delancey lives in Seward Park Houses. All of these buildings contribute to a cinematic fabric that serves as backdrop to the story of immigration and class struggle in New York City. If only the walls could talk!

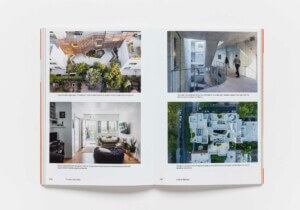

Co-op City’s architecture is vertical, as seen in Zara Pfeifer’s photo essay, but its ownership system is horizontal. The model was designed by Abraham Kazan, head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers (ACW) Credit Union who went on to start the United Housing Foundation (UHF). Kazan’s cooperative ideal, according to Tony Schuman in his 1997 essay Labor and Housing in New York City, was inspired by the Rochdale weavers, a profit-sharing movement in England founded in 1844, which Jessor’s Rochdale Village in Queens takes its name from.

Under Kazan’s leadership, the ACW built co-op grocery stores, milk deliveries, pharmacies, optician services, furniture distribution co-ops, insurance programs, and even energy distribution centers for its shareholders all over New York City. (Residents of Kazan’s buildings refer to themselves as ‘shareholders’, not ‘tenants’, because they have equity in their homes.) In short, Kazan brought lofty ideals that informed famous modernist projects like Karl Ehn’s Karl Marx-Hof (1927-30) in Vienna or Bruno Taut’s Horseshoe Estate (1925-33) in Berlin to the Big Apple. At Kazan’s buildings, working mothers were brought into design and planning: Domestic labor was redistributed within the estates between shared kindergartens and kitchens, much like Moisei Ginzberg’s Narkomfin in Moscow (1930).

Abraham Kazan and Herman Jessor’s grandest accomplishment, Co-op City, can be understood as a city within a city. The complex has its own government, its own ZIP code, and even its own newspaper: The Co-op City Times, which has a print run of 27,000 copies published weekly. Riverbay Corporation is the name of the 15-member Board of Directors that presides over the 44,509 shareholders that call Co-op City home. This body is made up of shareholders elected to office; it’s responsible for setting policy in the community, and interfacing with New York City and State officials. An industrial power plant provides electricity, heat, hot water, and air conditioning to every unit.

Subletting at Co-op City is prohibited. Shareholders in these units don’t pay market rate like a lot of us who cough up large sums of our paycheck to private landlords. By comparison, Jessor’s apartments are bought at “low per room prices but do not realize a profit on resale,” wrote Tony Schuman. “The units were made affordable by real estate tax abatements, low-interest mortgages, and Jessor’s cost-conscious design,” Schuman elaborated. In short, Jessor’s units are decommodified, allowing for working class New York families to live close to their jobs and schools. In the most expensive city on earth, these flats can be a lifeline.

Fifty years after Co-op City topped out, it continues to entice debate. In Freedomland: Co-op City and the Story of New York, Annemarie Sammartino leans upon her childhood in Co-op City to tell its remarkable story. She delivers first-hand accounts about the early optimism driving Co-op City’s planning by Abraham Kazan. She even retells the epic rent strike that took place there led by the Bronx Maoist-slash-Co-op City resident Charlie Rosen. The grand affair lasted 13 months and captured headlines throughout New York City, marking the largest rent strike in its history.

In Freedomland, which takes its name from the amusement park Co-op City was built on, Sammartino pooh-poohs yesteryear’s critics like Ulrich Franzen and Ada Louis Huxtable for focusing too much on the estate’s aesthetics while overlooking its impressive economic and racial egalitarianism that stands strong to this day. Critic Sybil Moholy-Nagy said Co-op City had “deadly antiurbanism”—which means what exactly? In The New York Times, Huxtable lambasted Co-op City as having “uninspired architectural design”, and “sterile site-planning.” In Progressive Architecture, Ulrich Franzen accused Herman Jessor of designing architecture for the “silent majority,” an insinuation that Co-op City shareholders were a bunch of white flight Nixon voters trying to get out of the Bronx. “From the time it was founded,” Sammartino wrote, “Co-op City residents have been castigated as fearful white racists who abandoned the Grand Concourse and were ultimately responsible for the collapse of much of the Bronx in the 1960s and 1970s.”

In her book, published in 2022, Sammartino says this popular narrative propped up by Franzen is an oversimplification and inaccurate. If Franzen had done his homework, Sammartino pointed out, he’d have noticed a very different demographic: The families moving into Co-op City were 75 percent white at first, but they were mostly leftist Jews from the trade unions, as well as first generation Black and Latine families, including the young Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor. In her memoir, Sotomayor said fondly of her childhood at Co-op City that “a much wider world was opening up to me” there. She said “The differences [in this multicultural development] were plain enough, and yet I saw that they were as nothing compared with what we had in common.”

Franzen, Huxtable, and Moholy-Nagy however were far from alone in their Co-op City lamentation: New Urbanists hated the place, and neo-Trads hated it even more. One gaggle of opinionated Yalies said in 1968 that Co-op City was “an example of the bleak, inhuman, uninhabitable masses of stone, the products of a society so distorted in its values that it can offer nothing but ugliness to its less fortunate members.” Jane Jacobs came out in opposition to cooperative supermarkets at Jessor’s buildings, saying “a store like this would fail economically if it had competition” because, under Jacobs’ libertarian thinking, co-op workers had a “lack of friendliness.” No love for the Rochdale weavers!

This was a tough crowd indeed. In response to the haters, Jessor shook off Co-op City’s criticism as petit-bourgeois pedantry. “We are willing to pay for something practical, but we are unwilling to pay for art,” he said. After its completion, Denise Scott Brown was one of the first big names that came to Co-op City’s rescue. In her essay penned with Robert Venturi, “Learning from Co-op City,” the duo defended the estate, saying “Co-op City is not all right, it is almost all right,” and in their 1970 article for Progressive Architecture, Scott Brown and Venturi applauded Jessor for having the courage “to accept the ordinary on its own terms and do it well,” and give “the people something they want.” This iconoclastic opinion makes sense, given Scott Brown’s own training at the AA in London after World War II. In those postwar years, architects went to work for the planning wing at the Greater London Council, a socialist governing body responsible for rebuilding London as cost-efficiently and quickly as possible. Scott Brown was also well versed in the teachings of Team X’s Peter and Alison Smithson that espoused the virtues of large-scale, Brutalist planning.

Was Co-op City perfect? Certainly not. Every utopia has its cracks. Co-op City is notoriously hard to get to—it’s a 20-minute walk from the nearest subway stop (but a new Metro-North Rail Road station is slated for construction nearby in the next few years). When the rent strike at Co-op City concluded in 1976, it almost bankrupted the New York State Housing Finance Agency, and the UHF folded shortly after. There was also a new president in Washington, D.C. (Gerald Ford) who preferred smaller government, and set into motion austerity programs divesting from government-backed housing projects. So much of Co-op City’s construction costs were handed over to shareholders, prompting many of the original families to get up and leave. Crime and racial tensions plagued Co-op City for much of the 1980s until deals were made in 1986, 1991, and 1993 that procured much-needed support for the estate from New York State’s Division of Housing and Community Renewal (DHCR) under then New York Governor Mario Cuomo.

Today, Herman Jessor’s buildings aren’t the prettiest or most extravagant, but thousands of working class New Yorkers call them home. They recall the old adage about how “small is good but tall is necessary.” Amid a devastating housing crisis, this generation of urbanists can learn much from both Jessor and Co-op City. The north Bronx towers hovering over I-95 remind us of the utopian optimism that radicals employed not so long ago; beckoning contemporary architects to do the same.

Zara Pfeifer is a Vienna- and Berlin-based photographer who often trains her lens on architectural icons of the everyday. Her work has explored high-rise housing in her native Vienna, Berlin, and other cities. The photographs published here are the result of an artist residency in New York in 2023. These sections focus on Jessor’s architecture, but Pfeifer also documented the lives and apartments of co-op residents. Pfeifer is planning on photographing more of Herman Jessor’s buildings in summer 2024 for a forthcoming book project.