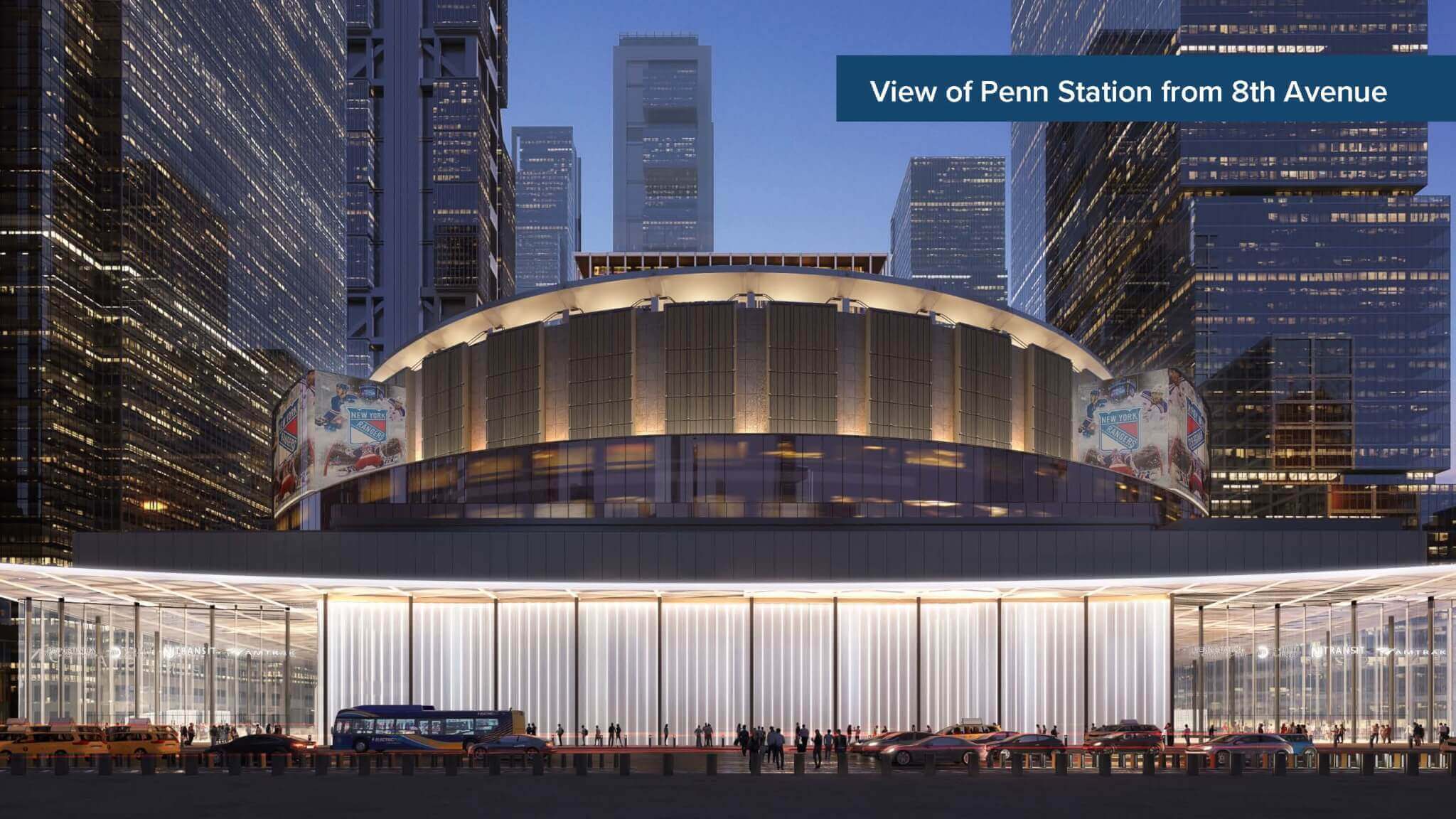

City Council’s vote on the operating permit for Madison Square Garden (MSG)—a 48-0 decision to extend it only five years, not in perpetuity as MSG Entertainment (MSGE) sought—marked a potential turning point in the effort to balance public and private interests in renovating Penn Station, New York’s long standing infrastructural problem.

Among experts commenting on Penn, former New York City Transit Authority director Andy Byford has gone on record favoring a full site overhaul. In a surprise appearance at a ReThinkNYC public online seminar on July 20, Byford said, “You can’t fix [Penn] by just putting in a few light boxes, by just [raising] the ceilings, by just widening a few corridors. If we’re going to do all of that, why not take the opportunity to fix the damn thing once and for all? Which is, I’m going to say: get rid of the pillars, which means move MSG, but at the very least, do something with the track configuration to enable through-running.” Byford spoke independently, not on behalf of Amtrak, where he now serves as executive vice president for high-speed rail; still, his perspective encourages observers who hope for transformed operations rather than merely improved appearances.

Those following the drama surrounding Penn Station will be familiar with the plans put forth by ASTM/HOK/PAU—a public-private partnership (P3) unveiled as reimagining the station with MSG still in place atop—and alternate visions by City Club, ReThinkNYC, and other advocates for moving MSG completely. But the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) is a major protagonist in the plot; its master plan involving FXCollaborative, WSP, and John McAslan + Partners remains active and evolving.

The MTA’s master plan could even move forward toward design iteration if Empire State Development’s General Project Plan (GPP) is formally withdrawn. It’s currently in limbo as its ten commercial tower funding mechanism was deemed nonviable by Vornado Realty Trust last February and was “decoupled” from renovations by Governor Kathy Hochul on June 26.

Yet as the media continues to circulate binary stories of the MSG versus no-MSG factions, Jamie Torres-Springer, President of MTA Construction and Development, believes that coverage of the railroads’ advancing plan is being crowded out of public awareness. “We spent two and a half years producing a master plan,” he said, “and creating a consensus around that plan amongst the three railroads, which is no easy task.”

The three railroads who own and/or operate out of Penn Station—Amtrak, NJ Transit, and the MTA—are worried less about aesthetics and more about performance. In terms of the P3 and other plans, the railroads see two main contentions: Does New York City keep or relocate MSG? And do tax dollars go toward a transition to through-running service or maintain the status quo?

AN’s previous reporting has centered on these plans, highlighting their architectural input and expertise. But how exactly does the MTA’s proposal differ from the designs it shares headlines with? To start, it centers the issue of functionality. “My job is to produce transportation benefits for that vast majority of riders,” said Torres-Springer, speaking to his focus on the roughly 600,000 riders who pass through Penn every day. They, he argues, not other vested interests in the area’s revitalization, should be the primary beneficiaries of any renovation. Much of the operational debate involves through-running, a topic that transit specialists and community-activist groups emphasize and most officials are reluctant to touch, though Torres-Springer has gone on record describing a study of through-running under way, potentially revising a preliminary study’s conclusion against it.

Through-Running: What It Means and What It Promises

Through-running means track systems where trains can arrive in one direction and continue onward on the same track. These systems don’t entail trains parking and then being forced to back out, as they do at Grand Central Terminal. Through-running is the norm in more advanced railroad networks worldwide and is lauded for its ability to greatly improve train speeds, dwell times, and scheduling. If adopted at Penn Station, this means more frequent and efficient rail service for the eastern seaboard.

Meanwhile, the MTA’s master plan is approaching the 30 percent design stage, a level nearly ready to go out for design-bid-build; it is currently a framework expressing stakeholders’ intent, not a specific design. Urban planner Jack Robbins of FXCollaborative reminds competitors and their advocates that his team has the commission from the railroads: “While we welcome the free marketplace of ideas, our design is the one that’s moving forward to the 30 percent design, and then ASTM and everyone else will have a chance to bid on it at that point.”

The Empire Station Coalition, including the City Club, ReThinkNYC, Congress for the New Urbanism NYC, and other groups, continue to critique the railroads for resistance to through-running. Critics in this camp, particularly ReThink, insist that through-running represents the difference between a cosmetically acceptable station that is still hampered by the long train-turnaround times inherent in terminal operations and a station that could provide the world-class service that New Yorkers deserve, and the national network arguably needs.

To MSG or Not to MSG

Recognizing that the station’s current condition (no daylight, low ceiling heights, very compressed) strikes users as horrible, FXCollaborative’s architect Stephan Dallendorfer noted that, “your gut reaction is ‘Well, let’s get rid of the roof,’ meaning MSG, and then that solves everything.” But he responds to the ASTM P3’s proposal to buy, and subsequently demolish, the Hulu Theater along Eighth Avenue, saying, “If you remove the Hulu Theater, that’s great, but you still have Madison Square Garden above you.” The five-year window is now city government’s chief form of leverage over MSGE (at least on critical points including safety upgrades, property concession, and truck loading, if not relocation), but its effectiveness depends on faith that the Dolan family, owners of MSGE, will not simply ignore the message, as it did the ten-year extension in 2013.

The new permit deadline leaves MSGE the alternatives of moving, hardballing the city again, or reaching an accommodation with the railroads that addresses the concerns of their initial Compatibility Report. An MSGE spokesperson responded to AN’s inquiry about City Council’s decision as follows: “As invested members of our community, we are committed to improving Penn Station and the surrounding area, and we continue to collaborate closely with a wide range of stakeholders to advance this shared goal.”

The ASTM/HOK/PAU P3 and the MTA’s official plan are premised on MSGE’s immobility, despite ongoing efforts to persuade MSG to move, clearing space for more unconstrained rail operations. As reported by AN, two groups lobbying for this relocation, the City Club and ReThink, saw their petitions dismissed in court on September 19, but ReThink spokesman Sam Turvey has indicated that petitioners are considering an appeal.

The Bigger Picture

Some critics agree with Torres-Springer on improving Penn Station for its 600,000 daily riders but insist that the new station must also dramatically scale up the benefits and the expectations. Robert Paaswell, former head of the Chicago Transit Authority, argues that the principle behind transit improvements on any scale outweighs everything. Nothing less than the future of American rail, he says, is at stake.

“This is a unique chance,” Paaswell said. “New York City and the east coast of the U.S. cannot exist without a really strong high-speed rail network to compete with the E.U. and Asia. If we don’t, slowly we’ll find that we just can’t compete. We do need high-speed rail. We can’t afford to have the airlines shut down any time there’s a thunderstorm.”

Byford favors “something similar to the Elizabeth Line… something that has that economic regenerative impact in New York.” Through-running service in London, on both the Elizabeth Line (Crossrail) and the north-south Thameslink, has been a boon to businesses and housing, he said.

Amtrak declined requests for an interview with Byford, noting that his current duties involve high-speed systems elsewhere in the U.S. Still, ReThink’s Turvey suggests that Byford would be a good choice to oversee a high-level evaluation of through-running options that would be more comprehensive than the WSP/FXCollaborative 2021 white paper on through-running, a preliminary study that both ReThink’s communiqués and a detailed analysis by mathematician Alon Levy, a fellow at NYU’s Marron Institute of Urban Management, describe as flawed and marred by conflicts of interest.

The economics of transportation, Paaswell tells his students, boil down to a basic principle: “Transportation creates access, and access creates value.” He notes that France is discouraging flights under 500 miles and favoring rail; China has cut the Beijing-Shanghai travel time, a distance comparable to New York-Chicago, to four hours with a maglev line; and England is expanding high-speed rail service: “They’ve done Crossrail, they’re thinking of Crossrail Two, and these don’t come up as crazy ideas,” said Paaswell. “But they come up with ideas for debating and setting timetables and finding money for it. We don’t have that ability here, where we have to find money every single year. And I think that puts the MTA at a disadvantage. It means it has to play politics for whoever’s in political control at the time.”

Could Amtrak Make the Right Connections?

The infrastructural view of the Penn complex is not obvious in the publicized renderings showing attractive new street-level designs, yet the priority of operations over visuals is one principle where the railroads and some of their sternest critics are in substantial agreement. Still, through-running remains a point of contention. Apart from Torres-Springer’s mention of the study under way, most insiders remain reluctant to consider through-running on the record, though Amtrak allows a degree of daylight on the topic. Jeannie Kwon, Amtrak’s vice president for capital delivery, said, “Over the past three years, Amtrak and our railroad partners have developed a conceptual master plan to serve as the starting point for the station’s reconstruction,” she continued (emphasis hers). “We expect this to evolve; no completed megaproject looks exactly the same as its conceptual design.” Her team recognizes and respects ReThink’s analyses, and she told AN, “Amtrak and our partners are giving careful consideration to the question of through-running operations at Penn Station, but see many challenges with relying exclusively on through running as a solution to doubling Northeast Corridor capacity.” She also notes that Amtrak has not taken a position on MSG staying or moving, deferring to City Council on that subject.

Much depends on whether the study in progress will address the nuts and bolts of conversion to through-running, including the feasibility of platform widening, the vertical clearance near the Seventh Avenue subway, and methodologic disputes over cost estimates. (The well-publicized overruns in the East Side Access project for the LIRR also give critics ammunition for arguments that MTA financial figures must be interpreted with more than a grain of salt.) At this writing, the date of this study’s completion remains unknown.

Penn-watchers remain braced for surprises. The complexity and contingency of the situation necessitates that serious assessments avoid both a naive perfectionism that would defer decisions indefinitely and a premature fatalism about what is politically achievable. (Premature fatalism toward public transit, after all, was part of the reason we lost the original Penn Station in the first place.) As debate swirls around a master plan on the verge of welcoming fresh designs, one wonders: Is it too much to hope that Amtrak and its rail partners might somehow think national and let Byford be Byford?

Bill Millard is a regular contributor to AN.