By more than one measure, Jackson, Mississippi, is one of the nation’s unhealthiest cities. In 2017, it was named the fattest city in America based on 17 indicators, including obesity rates, levels of physically active adults, and access to fresh produce. In fact, nearly one-fifth of city residents are considered food insecure. The state of Mississippi does not fare much better—for the last eight years, it was reported as the most food insecure state in the country, even though agriculture is the state’s top industry.

It’s not just that Jackson has only 17 grocery stores for a population of nearly 170,000—that’s one per nearly 10,000 people. But the food that is available is disproportionately tipped toward fast food and gas station items. As one scholar of Jackson’s food culture told the Clarion Ledger, “Hunger happens in between bags of chips.”

All of this is compounded by the city’s lack of viable public transit options. Jackson is designed around the car, but many residents, whose wallets are already stretched thin on federal food assistance dollars, don’t own one. Even those with groceries or farmers’ markets in walking distance are discouraged by the lack of sidewalks or crosswalks. These conditions are undergirded by decades of generational poverty and disinvestment due to white flight, unfavorable tax policies, and the state’s aggressive efforts to cut resources for Medicaid and limit food stamps.

But Jackson also has a long history of civil rights activism, and its residents in 2013 and again in 2017 elected mayors who promised nothing less than wholesale social and economic transformation. For Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, addressing Jackson’s food access challenge is part of his promise to make it “the most radical city in the world.” But rather than enlisting conventional strategies, the city has mobilized its long-range planning division to lead a new design-based initiative. Bolstered by a $1 million public art grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies, “Fertile Ground: Inspiring Dialogue about Food Access” brings together architects and artists alongside chefs, gardeners, food policy experts, and local institutions to facilitate a year of community-engaged interventions at three sites in the city. The project will culminate in a citywide exhibition in the spring of 2020, but ultimately it aims to establish a nonprofit research lab on food access that will operate on a permanent basis to sustain the momentum that is created.

The city invited an intriguing roster of architects and designers from around the country to participate in the multidisciplinary initiative: Kathy Velikov and Geoffrey Thün, directors of RVTR; Anya Sirota and Jean Louis Farges of Akoaki; Walter Hood of Hood Design Studio, and Jonathan Tate, who runs his namesake practice, Office of Jonathan Tate. Architects are central to the project, said Travis Crabtree, a senior urban planner with the city and one of the project’s coordinators. “When we first got the grant, people asked, Why are we spending $1 million dollars on an art project when we could feed people for a million?” he said.

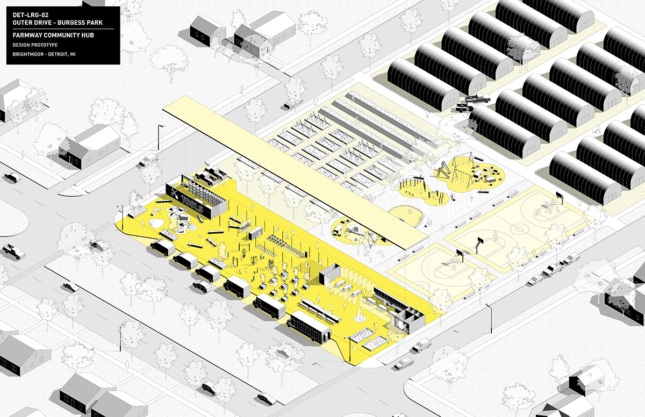

Looking more closely at what these designers bring to the table may illustrate what can be gained from this approach. The question of access is at the heart of practices like the Toronto and Ann Arbor, Michigan–based RVTR, led by Velikov and Thün, who are both associate professors at the University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning. In their ongoing project, Protean Prototypes, they conceive of public transit systems as platforms to address access to mobility, food, education, and health. They do this by mapping the social and spatial opportunities for access, connecting underserved areas with local actors who can bridge access gaps and by proposing lightweight spatial prototypes that overlay onto public transit infrastructure, such as bus stops and metro stations. The prototypes might include emerging tech like mobile produce vending systems and bike-cart shares alongside other programs with a small footprint like exercise equipment and book lending programs. Applying this method to Chicago, San Francisco, and Detroit, this complex systems approach brings together architectural and urban scale in new assemblages that amplify the resources already on the ground and take advantage of the larger urban context to channel them where they are needed most.

In Jackson, Velikov and Thün will focus their efforts at the Ecoshed, a 15,000-square-foot, open-air building on a 2-acre industrial site that borders two very different neighborhoods—the rapidly gentrifying Fondren and Virden Addition, one of the poorest in the city. For Fertile Ground, the Ecoshed will demonstrate a self-sustaining closed-loop food system and host the food lab, and eventually host the Fertile Ground nonprofit.

Anya Sirota and Jean Louis Farges of Detroit-based Akoaki will also focus their efforts at the Ecoshed. Their practice has engaged with the problem of food access through four years of work with an urban farm in Detroit, the Oakland Avenue Urban Farm. Sirota is also an associate professor of architecture at Taubman. Detroit provides a uniquely fertile landscape for thinking about urban food access. According to Sirota, Detroit has 1,300 urban farms, but none of them are sustainable. At the 6-acre Oakland Avenue Urban Farm, sustainability for Sirota and Farges has meant strategizing beyond economics alone. To them, urban farms are hubs for urban regeneration, and they realized that multiple layers of activity and programming were needed to realize that potential. Like Velikov and Thün, they see architecture as a way of “amplifying the activity that’s already happening on the ground, to stitch together new and productive alliances.”

Detroit may be 1,000 miles from Jackson, but the connection between the two cities runs deep. Like Jackson, Detroit is a majority African American city, with many residents who have ties to Mississippi and other southern states. Thus, the Oakland Avenue farm grows many heritage products from Mississippi. Likewise, the association to agriculture is similarly fraught in both cities; as Sirota noted, “We are highly attuned to the idea that going back to the land isn’t necessarily representationally positive to everyone.” Rather than framing urban farming as a return to an idyllic past (and glossing over the history of slavery and policies that led to the dispossession or denial of land to freed slaves), Akoaki’s urban farm work is firmly sited in the urban. “We’ve become astutely aware that the neo-rural is not rural; it’s something that deserves an aesthetic that hybridizes all the aspirations of the city and combines them with the necessity to produce picturesque landscape and food.” Thus the practice’s design of pop-up performance spaces next to the farm’s kale fields for the Detroit African Funkestra is based on the colors and shapes of shuttered music venues across Detroit.

Another participating architect, Oakland-based landscape architect Walter Hood, has extensive experience designing cultural and urban landscapes. Hood, who is also a professor at University of California, Berkeley’s will focus his efforts at Galloway Elementary in Jackson. The 4.3-acre, publicly owned lot is currently a playfield for a local elementary school. According to the city’s planning department, this site is located in a lower-income residential neighborhood with little public space and bordered by a major street dominated by fast food establishments. The theme here will be on food and community.

This is a good fit for Hood. His projects in Charleston, South Carolina; Macon, Georgia; Detroit, and Philadelphia, among other cities, demonstrate a steady thread of incorporating community feedback, local culture, and collective memory into landscape and urban design. In his Water Table installation at the Spoleto Festival in Charleston, Hood tapped into the ecology and history of rice production by mounting thousands of Carolina Gold rice plants in circular planters on a platform in a school courtyard, essentially recreating a rice paddy in downtown Charleston. The project resurfaced the link between rice production and the history of the slave labor that made Carolina’s rice industry possible. Afterwards, the project was dissembled and distributed, planter by planter, across schools and institutions in the area, and lived on to continue the conversation. This archaeological approach also surfaces in many other projects by Hood Studio, including its master plan for Detroit’s Rosa Parks neighborhood. Hood’s work has long engaged with the idea of “being a protagonist in design,” and, in reflecting on the future work in Jackson, asked, “How do we make a landscape powerful, so that once you do it, it has a resonance?”

Finally, at Congress Street, the third Fertile Ground site, New Orleans–based architect Jonathan Tate will bring his experience with food culture and exhibition design to a downtown storefront space. The Congress Street site is close to the heart of government and is intended to amplify the project to public officials and policymakers who work nearby.

For Tate, who designed the Southern Food and Beverage Museum in New Orleans, the task includes not only the adaptive reuse of an existing building but also the design of an outdoor parklet that invites the public in through greenscape and seating. The challenge will be to bring it all together—the art, the history, the contributions of numerous partners, and of course, engage critical feedback, in a downtown that goes quiet at 5 p.m. on weekdays. “Instead of a veneer you’re walking through, it’s about bringing the space of the building out into the street,” he explained.

The architects, along with other Fertile Ground team members, began site visits in April, and will develop their proposals until the citywide expo in 2020.