Since 2012, AN Media has hosted the Facades+ conference series, whose aim is to highlight the state of the art in building enclosure design and technology. Certain facade techniques and assemblies have predominated during this period. Many were necessitated by evolving climate standards and an awareness of the impact of buildings on carbon emissions. Others emerged from new economies of scale or more effective computational tools permeating the field. All display certain aesthetic affinities, pointing both to architecture’s past (e.g., stone and terra-cotta) and its future (bird-safe glass). To celebrate Facades+’s anniversary, AN looks back at enclosure trends that defined the past decade.

Flintstone Modern

Against a high-tech culture of the smooth and unspecific, some architects turned to more textured, archaic forms and materials.

Take Amin Taha’s 15 Clerkenwell Close in central London, completed in 2018. The apartment building overlays its glass curtain wall with uneven limestone and load-bearing masonry. Taha left the edges of the stone rough and preserved the scoring that indexed quarry cuts and stoneworkers’ treatments. Though offset from the building’s envelope, the limestone lattice remains integral to its performance; Taha claimed that it led to a reduction in embodied carbon by as much as 90 percent, as compared with typical concrete and steel frames. Critically hailed, the project was unpopular with neighbors, who unsuccessfully sued to have it dismantled.

Bahrain- and Amsterdam-based firm Studio Anne Holtrop has also exhibited a Neolithic bent, with buildings that are primitive and sleek at the same time. One of the office’s most recent projects, 35 Green Corner in Muharraq (2020), uses on-site sand-cast concrete panels indented with impressions of the surrounding landscape; this textural relief continues inside the narrow art storage space. Holtrop has said that he has “a strong wish to work directly with material and the way I can form it,” which can also be seen in the sand-blasted forms of his Cutting and Casting (2018) exhibition and his runway and retail designs for Maison Martin Margiela.

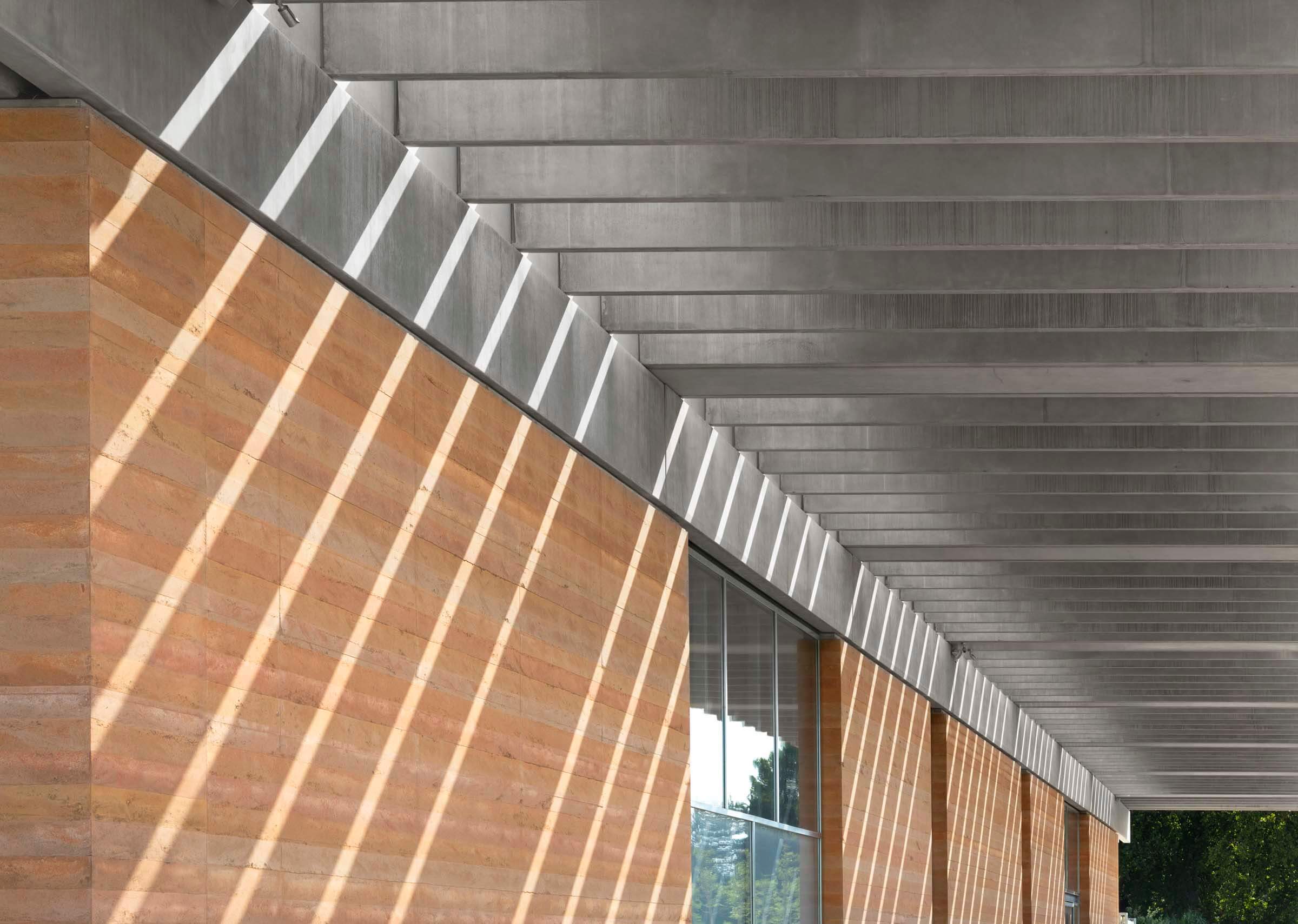

Similar to 35 Green Corner, Foster + Partners’ Narbo Via Archaeology Museum (2021) in Narbonne, France, balances earthy grit and glassy sophistication. The building features warm-colored concrete walls striated as if excavated from an ancient site. To achieve this dig-site look, Foster + Partners used local aggregates in different compositions, which resulted in a reddish clay hue. Insulating rammed-earth composites from Sirewall yielded a coarse texture while also upping the building’s thermal performance.

Tinkering with Clinkers

Brick is millennia old, but it achieved ubiquity only in the mid-19th century, when artisanal firing methods gave way to industrial manufacturing. The same standardization guided the material’s use in building design, where it was laid out in prescribed bond patterns. But thanks to new construction and computational techniques, brick has taken on renewed life.

In London, Bureau de Change’s five-story Interlock apartment building (2019) illustrates this evolution nicely. The outermost edge of the facade is set flush with that of its neighbor, whose sandy-colored bricks are arranged in a running bond. But then things start to happen: The Interlock’s blue-clay bricks appear to rotate like the teeth of a gear, as if the apartment face received an electric jolt. Using computational modeling, Bureau de Change generated 44 unique, interlocking brick types to achieve the rippling effect.

The windswept look has proved incredibly popular, with differences largely coming down to color and technique. In Sydney, the contorting facade of a 13,000-square-foot gallery (2019) by John Wardle Architects and Durbach Block Jaggers (literally) leaves an impression; the design team applied all sorts of tapers and cambers to get the gray, handmade bricks to cooperate. A project in Hyderabad, India, by Sameep Padora and Associates (also 2019) riffed on a similar motif, only here the corbeled redbrick bulges around windows for added protection from the hot sun. Stateside, for a northern Illinois residence (2018) Brooks + Scarpa and Studio Dwell created a 28-foot-tall twisting screen wall using a relatively simple method: They threaded reclaimed Chicago bricks onto steel rods following a computer-generated pattern.

New York is replete with revisionist takes on classic masonry. Apart from its height, a 50-story residential tower on the Upper East Side (2021) stands out thanks to an almost fetishistic flourish. Design architect DDG and architect of record HTO Architect worked with bespoke Danish brickmaker Petersen Tegl to arrange the 600,000 hand-fired and -laid clinkers that make up the facade; extruded modules at the corners add a spiny texture. Downtown in the West Village, David Chipperfield Architects’ Jane Street apartment building (2021) toys with neighbors, placing thin artisanal redbrick atop chunky, custom-red concrete lintels. Across the East River, at SO–IL’s recently opened Amant Art Campus in Brooklyn, white cement bricks are wielded in uncanny ways.

Alt-Glass

Almost as soon as it appeared at mid-century, transparent insulated glass revolutionized building design. Transformative though it was, it had its downsides—energetically taxing, the material became a death trap for birds in urban settings—which we’re only coming to full grips with today. As a result, architects began in the past decade to play with translucency and opacity, opting for printed and bird-safe glass, as well as silicas, polycarbonate, and ETFE, over traditional glazing.

At the Le Monde headquarters in Paris (2020), Snøhetta improved on a pixelated approach to glass facades that French architect Jean Nouvel had tested out at a Chelsea, New York, condo tower (2010). In Paris, Snøhetta reduced the envelope to a thin assembly of patterned and printed glass titles—20,000 in all—strung together with bent clips. Though the pixel metaphor embraced by the architects is by now old hat, the rainscreen seamlessly mapped onto the curvilinear form of the base building.

For the net-zero ArtLab (2020) on Harvard’s Cambridge, Massachusetts, campus, the Berlin-based design office Barkow Leibinger worked with Sasaki to create high-performance polycarbonate rainscreens. Common in European construction, polycarbonate offers a ghostly, but also cool, aesthetic that should be exploited more stateside. Steven Holl Architects has found great success with translucent glass in numerous projects, particularly those in hotter, sunnier climes. The firm’s design for the Nancy and Rich Kinder Building (2020) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, combats heat gain and glare through a bundle of semiopaque, custom laminated-and-acid-etched glass tubes. Holl wittily refers to the tubular screen as a “cold jacket.”

The Toronto-based architectural collective PARTISANS reached for a similar metaphor—a “building raincoat”—when it debuted a prototype for a deployable arrangement of ETFE in 2019. Of course, ETFE, or ethylene tetrafluoroethylene, isn’t glass but is increasingly being used in place of it. At the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, John Ronan Architects designed an ETFE cushion envelope for the school’s innovation center (2018); the milky white facade was the perfect foil for Mies van der Rohe’s moody Crown Hall next door. When Diller Scofidio + Renfro looked to shed weight from the Shed in New York (2019), the firm reached for ETFE, which presented a far lighter alternative to glazing.

At the Cutting-Edge

If glass seems outré to some, the material is hardly on the outs. In fact, architects have rethought applications and assemblies for glass with an eye toward combating its environmental defects. Their cutting-edge solutions have aimed at the same goal: transforming the building envelope from a plane to a three-dimensional field, with plenty of shadow-creating folds, edges, and soffits.

Formally, these facades approximate the appearance of diamond facets or crystal fractals. A case in point: SOM’s design for the Geneva headquarters of Japan Tobacco International (JTI) Headquarters (2015), whose double-skin facade comprises interwoven triangles. While typical double skins often require maintenance, the pressurized, closed cavity SOM developed for JTI prevents condensation and dust capture and minimizes air leakage.

In New York, the Studio Gang–designed 40 Tenth Avenue (2019) bares its crystalline teeth to passersby on the High Line. Two of the tower’s corners have been abraded into geode-like arrangements of diamond-shaped glass panels (12 types in all); the complex massing allows for afternoon sunlight to reach the elevated park directly behind the building. In recent years, Jeanne Gang and her team have applied a similar carving procedure to many of the studio’s glass projects. At the One Hundred residential tower (2020) in St. Louis, they interspersed low-E glazing with anodized aluminum panels across tiered floors. The tower’s fluted footprint multiplied the number of glazed corner units, which gave the unitized curtain wall a particularly sharp character.

Over in Berlin, Danish firm 3XN worked with facade engineer Drees & Sommer and structural engineer RSP Remmel + Sattler to scale up the faceted trend for the ten-story cube berlin (2020). Rather than chisel away at the edges of the building mass, 3XN set itself the task of working within a more regulated whole, i.e., a cube. From there, the design team applied a series of pinches and tucks, realized through great triangular swaths of solar-control glass that sometimes pull away from the perimeter to create terraces. From afar, the office building looks like a monolithic block, but when viewed closer up, it has a much more dynamic presence.

But faceting isn’t only for glass. At the University of Cincinnati’s Gardner Neuroscience Institute (2019), Perkins&Will worked with Structurflex to devise a tensile polyester mesh that pulls away from a curtain wall. Saw-toothed in profile, the screen minimizes glare and solar load, while also obviating the need for internal shades.

In Guangzhou, Zaha Hadid Architects’ (ZHA) design for the headquarters of Infinitus China (2021) sums up the faceted fetish of the 2010s, made possible by parametric modeling software. Over the years, the firm has courted complexity with every one of its projects, and things were no different at Infinitus Plaza. ZHA outfitted a double-curved facade with perforated, lozenge-shaped aluminum panels that programmatically pull apart or tighten up where sunlight is least or greatest.

The Fin-essed Facade

Many buildings today mount giant protective armor on their exteriors, as if they were due to enter battle. All manner of prickly protuberances—spikes, fins, radial notches—characterize the trend.

But there are plenty of chinks in this armor, and intentionally so: These buildings don’t want to battle the sun as much as make a pact with it.

Noted for their solar shading abilities, the devices seem especially popular with institutional and educational clients. The facade of Payette’s Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Complex (2016) at Northeastern University showcased tightly spaced and angled aluminum panels in a moiré pattern.

Meanwhile, the Miller Hull–designed Hans Rosling Center for the University of Washington (2020) deploys angled glass fins to balance daylighting and glare concerns; fixed to a unitized curtain wall system, the projections appear to wave in the breeze. At Harvard, the LEED Platinum–certified Science and Engineering Complex (2021) sports a high-tech brise-soleil comprising hydroformed stainless-steel elements, a first of its kind. The project was designed by Behnisch Architekten, which made extensive calculations to determine the profile of each of the 14,000 facade panels.

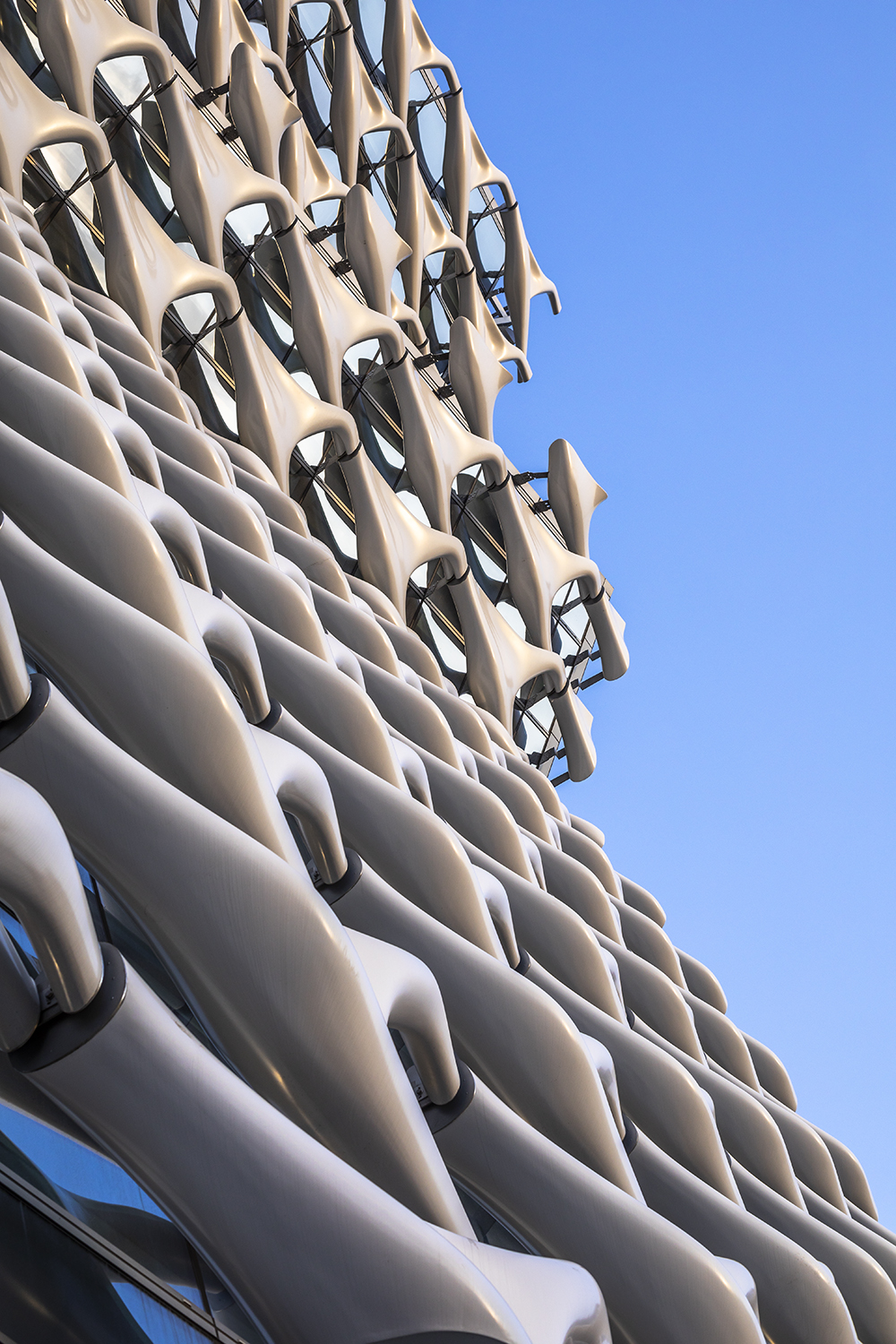

Computational modeling is key to the success of all these schemes. Throughout the 2010s, Morphosis, the experimental Los Angeles architecture studio, invested heavily in this research. For the headquarters of The Kolon Group (2018), a Korean conglomerate and leading textile manufacturer, Morphosis conjured a sunscreen of interlocking, parametrically designed knots using its client’s own fiber products. (Though pillowy in appearance, the elements have a tensile strength greater than iron.) For a Casablanca, Morocco, office tower (2019), the firm developed a striking, diagonal lattice screen crucial to the project’s LEED Gold certification. But Morphosis upped the ante at its conference center (2021) in Nanjing, China, whose unfathomably complex brise-soleil contains 90,000 unique metallic panels.

Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, we find maybe the most self-conscious display of the trend. The Museum of Modern Aluminum (2022) in Nonthaburi, Thailand, seems frozen right at the moment of an explosion. Hundreds of aluminum shards—the museum’s namesake material—jut out from all sides of the building to form a dynamic composition. Eschewing a computational approach, HAS, the Bangkok- and Shanghai-based office behind the design, resorted to analog means such as scale models and 1:1 mockups.

Returning to the States, San Francisco studio IwamotoScott has finessed facades for that most neglected yet ubiquitous typology: the parking garage. For the 3rd Street Garage (2020) in the Golden City, the firm created a porous envelope of bent, petal-shaped aluminum panels, arranged vertically in the manner of a DNA coil. The project builds on an earlier 2015 garage commission at the Miami Design District, where IwamotoScott fashioned a delicate folded screen from staggered aluminum fins.

In New York, studio Archi-Tectonics assembled prefab panels into a trellis to passively shade a Soho townhouse (2020). Principal Winka Dubbeldam refers to the partly operable, mixed-material facade as a “climate skin.” It’s a moniker that could easily apply to all these projects, which no longer parse out the armor from the epidermal layer beneath.

Not Your Mama’s Terra-Cotta

Terra-cotta, that low-tech-seeming ceramic cladding with ancient roots, has made a huge comeback in recent years. New climate standards have bolstered interest in time-tested and more natural materials, with fired clay and glazed porcelain rising to the top. Today, tiles and panels in sizes ranging from a foot to 10 feet are readily available from companies such as Terreal North America, Shildan Group, and Boston Valley, though some architecture firms prefer to come up with their own solutions.

The London architecture office AL_A clad the swooping form of Lisbon’s MAAT Museum (2016) with custom glazed porcelain tiles, just as it would for its expansion of the Victoria & Albert Museum a year later. In New York, Selldorf Architects set off a terra-cotta trend when it wrapped a Soho apartment building (2015)

in the stuff, colored a deep russet to match its brick-clad neighbors. Morris Adjmi Architects opted for charcoal porcelain panels for a wedge-shaped mixed-use block (2018) in the NoHo district. The SOM-designed 28&7 residential development in Chelsea is positively gleaming, thanks to its elegant black, glazed terra-cotta grid.

On the opposite coast, Kevin Daly Architects developed a composite terra-cotta rainscreen for UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music (2015) that helped the building perform 20 percent better than state codes. And in Denver, the Olson Kundig–designed Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art (2018) offered another lesson in modifying off-the-shelf components. The firm worked with John Lewis Glass to devise gold leaf–backed glass inserts set between honey- and flaxen-hued glazed ceramic strips, with the result mimicking the mottled color of autumn leaves.

One of the most surprising things about terra-cotta is how readily it lends itself to bespoke shapes and dynamic compositions. The ribbed facade of the Meeting and Guest House at the University of Pennsylvania (2021) sets a baseline; to realize the design, Deborah Berke Partners created volumetric “baguettes” that were manufactured by Shildan. A more complex case study is the Health Sciences Innovation Building at the University of Arizona (2019), designed by CO Architects. For the building facade, the firm modeled ten types of terra-cotta, which were used to generate 3,000-plus panels; they add a distinctive texture that recalls adobe construction. SHoP Architects played a similar game at 111 West 57th Street (2022) in Manhattan. The firm developed 13 unique dies that NBK Terracotta used to fabricate the 43,000 glazed panels that snake up the supertall’s facade.